|

PROTON POWER

UC Davis ophthalmologists fight ocular melanoma with charged protons

On Sunday, April 2, 2006, Michael J. Bone, an athletic Sacramento-area veterinarian, noticed flashes of light in his right eye as he went about his weekend activities. Reading the newspaper Monday morning, he spotted a crescent-shaped shadow in the central vision of the same eye. On Tuesday evening, the shadow was still there. Bone's wife called the doctor the following morning.

By Thursday afternoon, following a battery of tests, Bone had a diagnosis. The avid skier, fly fisherman and father of three had choroidal melanoma, a cancer of the pigmented layer of the eye that lies behind the retina. The tumor was about one-third of an inch in diameter and just under a quarter-inch deep.

Tough choices

For decades, surgical removal of the eye, known as enucleation, was the only treatment for ocular melanoma. Enucleation remains a standard treatment for the disease today, but Bone also had another choice: UC Davis is the one of six centers nationwide that can treat the lesions with proton-beam therapy.

After a weekend to research his options, Bone chose proton therapy. "It seemed the most advanced, with the best success rate and lowest risk of vision loss," he said.

Protons vs. gamma rays

Conventional radiation therapy kills cancer cells using gamma radiation. However, it has limitations as a treatment for tumors near delicate structures like the optic nerve or retina.

Gamma rays deliver energy to all the tissues they travel through, from the point they enter the body until they leave it.

proton-beams, in contrast, drop almost all of their energy on their target. Dosing is so exact that tissue just one-tenth of an inch from the target receives almost no radiation. Because damage to healthy tissue is minimized, doctors can treat cancers with higher and more effective radiation doses.

Since 1994, the cyclotron housed in the Crocker Nuclear Laboratory on the UC Davis campus has generated protons used in the treatment of about 800 eye tumors in patients from as far away as New Zealand. Tumors have diminished or disappeared in more than 95 percent of cases, with better long-term survival rates than those seen in patients who have their eyes removed. In addition, most proton patients retain useful vision in the treated eye.

Collaboration with UCSF

The first step in Bone's treatment was a 75-minute operation at UC Davis Medical Center, in which Susanna Park, an associate professor of ophthalmology and vision sciences, stitched four tantalum rings to the back of his sclera, the tough white outer coating of the eye, along the perimeter of the tumor. The rings, which don't require removal and remain in place, show up in bright relief on X-rays, serving as clear guideposts for the proton-beam procedure.

|

|

| |

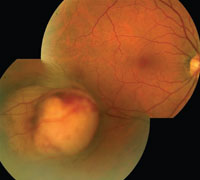

Micheal Bone's choroidal melanoma can be seen in these photos of his retina. The tumor is the lighter-colored lesion in the lower left image. |

|

|

Step two, a few weeks later, was a trip to UC San Francisco, where experienced technicians fitted Bone with the custom components he would need during the treatment: a bite block and partial face mask, to help immobilize his head, and a propeller with graduated blades to modulate the proton-beam to the precise depth of his tumor.

Additional advance work took place at the UC Davis cyclotron, where machinists fashioned a hole the shape of Bone's tumor in a brass fitting known as a collimator (pictured on cover); the collimator molds the beam to hit just the tumor and a small safety margin of tissue bordering it.

Treatment near home

UCSF physicians have offered proton-beam therapy for ocular melanoma at the UC Davis cyclotron since 1994. When radiation oncologists, physicists and technicians at UC Davis Cancer Center take over the jobs now being done in San Francisco, proton-beam patients will get all of their care in Sacramento and Davis.

"We're trying to make proton-beam therapy more accessible to patients throughout the Central Valley and inland Northern California," said Park, who trained in proton-beam therapy as a resident and retina fellow at Harvard University/Massachusetts Eye & Ear Infirmary.

At the same time, researchers at UC Davis Cancer Center and Lawrence Livermore National Laboratory are at work on a new-generation proton-beam machine that promises to make the therapy more available worldwide. The machine, powerful enough to treat cancer anywhere in the body, will be tested at UC Davis Cancer Center.

Instructed to stare

Bone's first proton-beam treatment took place on Tuesday, June 6. That afternoon, he drove himself to the UC Davis cyclotron from his Fair Oaks veterinary practice.

He took a seat in the straightbacked metal chair in the lab's 8- by 12-foot treatment room, tilted his head back for an anesthetic eye drop, then leaned into the rigid face mask and bit down on the bite block. A belt securing his forehead to the back of the chair was cinched tight; clips were attached to his eyelids to prevent blinking. Bone was instructed to stare fixedly at a small red light on the proton therapy apparatus. A camera, focused on his eye, stared back. Any movement of Bone's head would be relayed immediately to a monitor on the other side of the door.

After assuring themselves that Bone was in proper position, the medical team — a radiation oncologist, physicist and two technicians — cleared the room and took up positions at a control center around the corner.

Medical physicist Inder Daftari activated the beam. Exactly two minutes later, Daftari turned it off.

Talking about the procedure immediately afterward, Bone said it wasn't as bad as he thought it would be.

"I just thank God I have these great doctors, great machines, great people to take care of me," he said.

Over the next three days, he returned to the lab for three more two-minute treatments. Five weeks later, Bone was back at the UC Davis Ophthalmology Clinic for a follow-up appointment with Park. He had no vision loss. The tumor's growth had been arrested. And he had better than a 90-percent chance for a full cure.

His family and friends are as relieved as he is. Bone's best friend and fishing buddy, on first hearing about the melanoma, had quipped: "Well … just so I don't have to tie on your flies for you."

A few days after his final proton-beam treatment, Bone was waist-deep in the American River, casting flies. He tied them on just fine. He didn't even need to squint.

|