Dileep Bal, who helped make California the nation's

no-smoking section, is teaming up with UC Davis Cancer Center to snuff out ethnic

disparities in cancer

Dileep G. Bal's three-letter last name may have become a four-letter word to tobacco and fast

food companies. So be it.

It's fine by Bal, chief of the Cancer Control Branch of the California Department of Health Services,

that he's been politically unpopular from time to time.

What does put him on edge, however, is getting any undue credit for the state's leaps forward in cancer

control.

And they have been significant leaps: California adults now purchase about 45 packs of cigarettes per

person per year.

That compares to about 120 packs per person in 1998, when the state passed Proposition 99, which added

a 25-cent tax to each pack of cigarettes sold in California, and remains less than half the average pack-per-person

rate for the other 49 states combined.

"The community norm 15 years ago in California was ubiquitous tobacco use," Bal says. "Now,

we've cut them off at the pass. Since 1995 you can't smoke in restaurants; since 1998 you can't even smoke

in bars. We have all kinds of occupational health controls; we have youth-access regulations. We have

all kinds of educational programs and media programs. And all that in a political environment."

The Cancer Control Branch is taking the same approach to combat dietary risk factors for cancer. "McDonald's

and various fast-food outlets and producers — the junk-food producers — they all peddle their

stuff using Madison Avenue glitz," Bal says. "And we do counter-advertising."

Bal has been given armfuls of awards for his branch's cutting-edge work, a fact he finds a bit embarrassing.

Credit instead should go to a team effort that encompasses mainly his state colleagues, cancer centers,

private organizations and local public health officials, he argues. "Collectively," he says,

"we have had an impact."

In his own office, Bal preaches using the "we" word not the "I" word, and tries to

live up to that principle. "I have no intention of taking credit for what this has become, but I

had the wisdom to hire some very good people and to provide them the resources that were needed,"

he says. "I've had the privilege to work with a group of very clever people who have built empires

with my assistance, providing funds on occasion and on occasion providing them political cover. Equally

important, I've stayed the hell out of their way."

Public servant

For all his modesty, Bal has plenty of admirers. Marc Schenker, professor and chair of public health

sciences at UC Davis, says Bal "has been instrumental in advancing public health in California."

"His contribution to the health of Californians is immense," Schenker says. "He is a dedicated,

selfless public servant who has truly made a difference."

Says Moon S. Chen, Jr., professor of public health sciences and co-leader of the UC Davis Cancer Center's

Cancer Prevention and Control Program: "If I had to name a single individual who was responsible

for making California America's no-smoking section, it would be Dileep Bal."

But Bal says that what he's done, as much as anything, is give permission for people to "try crazy

things."

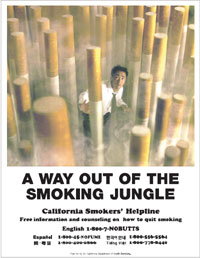

Nowhere has the branch's creative approach to motivating healthier lifestyles shown more results than

in tobacco use in California. Bal characterizes the effort as a David vs. Goliath battle — a state agency

going toe-to-toe with big tobacco, often on the industry's own turf: advertising.

Hitting hard

"We went to the heart of the beast. We demonized the industry," Bal says. "We said, ‘They're

peddling a product that's as addictive as cocaine and heroin and causes nearly half a million deaths in

the United States every year.' "

"They get people hooked with their predatory marketing practices … and once they draw them in with

advertising, they maintain them as customers because of the addictive nature of the product. It was a

connection everyone knew but nobody had countered, so we went to the ‘community norm change model.' The

community norm was tobacco use, so we hit very hard."

The Cancer Control Branch hasn't stopped there.

"We're doing some of the same things with diet. Some of the people responsible say comparing fast

food to cigarettes is an overdrawn analogy. I don't think so," Bal says. "They say we're acting

like the ‘food police' — it's not the food police. We're simply trying to move consumers more towards

fruits, vegetables, trying to keep them away from alcohol, trying to get them to exercise more —

again, to change community norms. We're countering the predatory marketing practices that take primarily

low-income people and get them habituated to fast food, the wrong food."

Changing community norms is the only way to tackle the country's leading killers, like cancer, coronary

heart disease and obstructive lung disease, Bal argues. Gone are the days when health authorities believed

top killers might be foiled solely in the lab.

"The plagues of today are all related to today's lifestyles: using tobacco, using drugs, using alcohol,

being too fat, being indolent, not eating the proper things, not walking up stairs but taking elevators,"

Bal says. "So the question is: How do we change the current behavior of Americans, without doing

it in a way that intrudes into their personal rights and privileges?"

Trained as a doctor

Bal's own interest in public health dates to his early days as a doctor in his native India. Bal trained

as a physician at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences in New Delhi, India, where he specialized

in public health and preventive medicine. Practicing afterward in rural areas, he witnessed the chasm

between health care for the rich and poor.

When he came to the United States as a scholarship student at Columbia in the late 1960s, Bal again found

a two-tiered health system in which the poor and uneducated — more often than not people of color

— didn't fare as well as the better-off and educated.

After graduating from Columbia and later Harvard, Bal began a career in academia at the University of

Arizona before opting for a life in public health. Before taking the helm of California's then relatively

small Cancer Control Branch in 1981, he headed the Pima County, Ariz., Public Health Department.

Over the years Bal has also served as the president of the American Cancer Society at both the state

and national level, while continuing to publish extensively and to serve as the principal investigator

of several major cancer prevention and control projects funded by the National Cancer Institute and the

U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention.

In addition, he has worked with UC Davis Cancer Center leaders to unite and coordinate the talents of

the two institutions in a partnership aimed at improving the health of all Californians.

Special relationship

Indeed, the deeply rooted relationship between UC Davis Cancer Center and the Cancer Control Branch of

the California Department of Health Services has never been closer. The relationship unites a preeminent

state health department with a major cancer center, in a concerted effort to prevent and control cancer

statewide.

For example, Dileep Bal holds an academic appointment at UC Davis, as a professor of public health sciences.

He also serves as the principal investigator for the Sacramento regional office of AANCART (Asian American

Network for Cancer Awareness, Research and Training). This National Cancer Institute-funded project, the

largest ever undertaken to reduce cancer in Asian Americans, is headquartered at UC Davis. It encompasses

investigators at seven other universities, from the University of Hawaii to Harvard. Bal provides regional

leadership as well as support staff and office space for Sacramento AANCART.

The Cancer Control Branch and UC Davis recently co-sponsored the 5th Asian American Cancer Control Academy,

which drew 450 public health experts and community leaders from around the country to Sacramento. Kurt

Snipes, chief of Cancer Control Planning, Research and Disparities for DHS, served as academy superintendent.

In addition, DHS staff provided extensive administrative support. And DHS research was prominent at the

academy. Included were reports on tobacco use, diet and exercise patterns, and cancer incidence and mortality

among Asian Americans in California.

Through AANCART, UC Davis Cancer Center and DHS have worked together to host quarterly cancer education

sessions for Sacramento's Asian American population, attracting about 125 people to each session.

With AANCART as a model, UC Davis Cancer Center and DHS are now developing new cancer-control initiatives

targeted at Sacramento's African American, Hispanic and Native American communities.

"It is personally very rewarding for me to do on-the-ground work with UC Davis folks," Bal

says.

Making the effort to change community norms, however well meaning, can bring plenty of heat — especially

when it comes to messing with the like of big tobacco companies.

"But," Bal says, "if people are injuring themselves, it's incumbent on us to point out

alternate ways of operating. That's what we do.

"Do people get upset? Sure. Does it faze us? No."

Bal says success is the key to getting things done in a shifting political landscape. "When you've

done things as controversial as we have, you have to have successes in order for people to back off. In

television and radio, you're only as good as your last Nielsen (ratings). Happily, the ratings for our

anti-tobacco ads have been phenomenal.

"Tobacco use in California has plummeted. But the proof is in the pudding — cancer rates in

California, which were lower than the rest of the United States to start with, are in an accelerated decline.

"We calculate that the net savings from our plummeting tobacco use rates is something like $8 to

$10 billion for California. So we have some capital built up."

For his part, Bal, 59, says he plans to retire in four or five years. He's not sure just what he'll do

yet, besides spending time with his wife, Muktha, and their children, Sarah and Vijay.

Rest assured, however, that — ever the team player — Bal will only be a phone call away. "If

anyone needs me in the cancer control fight," he says, "I'll be there."