Toxic Legacy?

The 2017 California wildfires were uniquely urban — incinerating thousands of human-made structures and their contents, from building materials to consumer electronics. UC Davis researchers are studying what kinds of known pollutants were released to linger on in affected communities — and whether the flames cooked up new toxins as well.

California’s historic 2017 wildfires destroyed or damaged more than 10,000 structures as they swept across the state, consuming an area the size of Delaware and leaving behind a swath of untold emotional and economic suffering.

But as flames tore through subdivisions and commercial areas in Santa Rosa, Ventura and dozens of smaller communities situated at the state’s expanding wildland-urban interface, they may have created another harmful legacy as well.

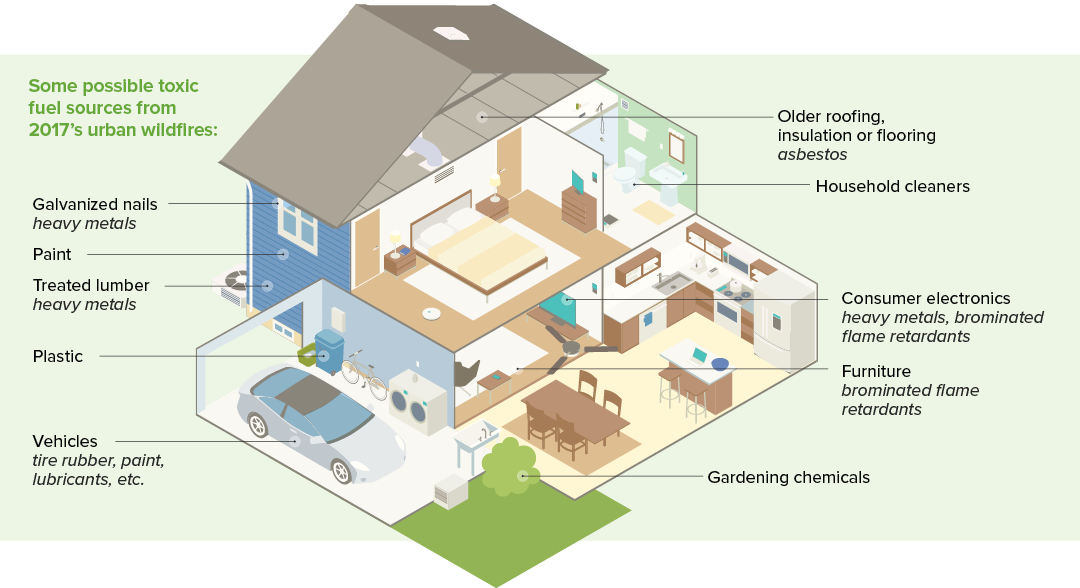

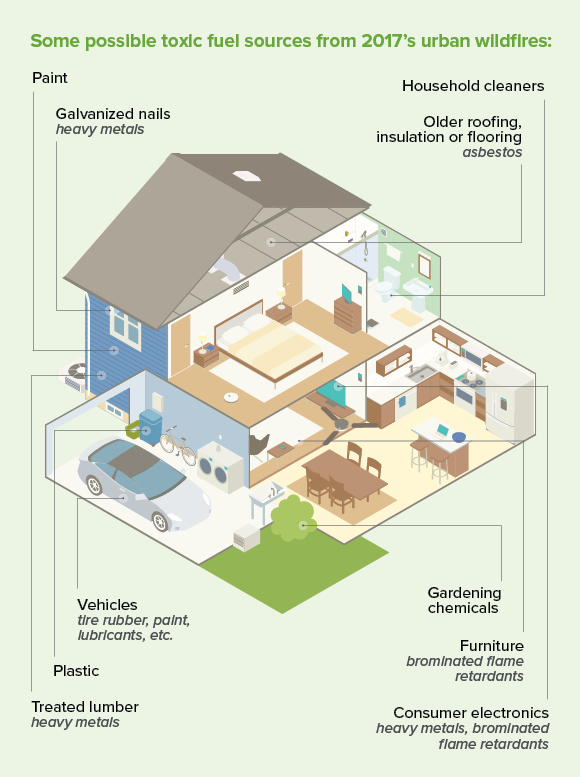

By incinerating a wide variety of construction and household materials at very high temperatures — including insulation, electronics, furniture, cleaning products, pesticides and the like — environmental scientists wonder whether the fires also generated unknown or previously unrecognized health hazards in the plumes of smoke and ash they released.

“Many of these fires were unique in their scope and intensity, as well as in the extent to which residential and commercial areas were impacted,” said Irva Hertz-Picciotto, M.P.H., Ph.D., an internationally known UC Davis environmental epidemiologist.

Now Hertz-Picciotto and her team of about a dozen other UC Davis public health researchers are trying to figure out just what byproducts are at play, and how they might affect humans. This January they launched the Northern California Fire and Health Impacts project, a comprehensive assessment of the health effects of last year’s major urban fires.

Also known as “Wildfires and Health: Assessing the Toll in Northern California” (WHAT Now-California), the effort was supported with initial funding from the UC Davis Environmental Health Sciences Center directed by Hertz-Picciotto. The center was established in 2015 with funds from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (NIEHS) to examine how pollutants affect disease and to find new ways of protecting communities from harmful exposures, while also training the next generation of environmental scholars.

In the case of the 2017 fires, the researchers hope their efforts will protect public health during the years-long recovery process in Northern and Southern California — and assist in preventing wildfire-related health problems in the future. The study has also received targeted NIEHS funding for “Time Sensitive Research Opportunities in Environmental Health Science.”

A unique catastrophe

The mixture of gases, fine particles and vapor in wildfire smoke can generally be nastier than many other types, though it’s not yet exactly clear why. And even before the peak of the 2017 fire season, UC Davis researchers were already questioning how pesticides used in forestry and agriculture — and retardant chemicals used in firefighting itself — could also contribute to wildfire smoke and affect the health of those who breathe it (see sidebar).

But massive urban conflagrations like last fall’s — and especially those that swept through Napa, Sonoma and Ventura late in the year — seem to offer an infinitely greater variety of man-made chemicals and fuels, ranging from thousands of car tires and televisions to millions of zinc-coated nails.

What chemicals were released? And did the superheated environment break down existing pollutants into novel types of constituents that may be harmful to humans in new and different ways — either alone, or when combined with other incineration byproducts?

“What we’re interested in looking for are ‘transformation products’ of household items that have burned in the fires,” Gabby Black, a fourth-year graduate student in agricultural and environmental chemistry who’s working on the study, told UC Davis communicators in January. Black is supported by a National Science Foundation graduate student fellowship.

The health hazards these compounds pose are not yet known, added Tom Young, Ph.D., a professor in the Department of Civil and Environmental Engineering and Black’s faculty advisor. “Conventional assessments rely on things that we already know are pollutants, such as industrial chemicals,” he said. “But we don’t know what new chemicals might have been created from combustion.”

Lingering particles

The UC Davis assessment examines both short- and long-term byproducts. While the Northern California fires were still burning, researcher Keith Bein, Ph.D., and colleagues from the UC Davis Air Quality Research Center collected samples of smoky air in the Bay Area and Davis for study. But even after the smoke cleared, scientists expect that dust in burned areas will still contain particles of fire ash for years to come — dust that can potentially be resuspended over and over again in the air, or washed into surface water or groundwater.

The researchers are honing in specifically on PM 2.5, or airborne particles less than 2.5 microns in size that can penetrate deep into the lungs (by comparison, the average human hair is about 70 micrometers in diameter). Ash samples have been gathered from a series of sites burned by the Tubbs Fire that devastated Santa Rosa in October, and will be analyzed by the latest techniques, which can generate high-resolution profiles of hundreds or thousands of molecules. Researchers will compare the samples to existing databases, and also look for new compounds.

“This was a very unique type of fire, an urban wildfire,” Bein told UC Davis communicators. “We (generally) know what wildfire smoke is composed of, but we have no idea what will be in this — we expect it to be very different.”

Social science element

In addition to sampling ash and air, researchers are also surveying residents of Napa, Sonoma and several other California counties affected by the fires or the smoke. The UC Davis Northern California Fire and Health Impacts Survey asked respondents how the fires have affected them and other household members, including their daily experiences and health before, during and after the blazes.

Through the answers, Hertz-Picciotto and her research team hope to better understand the effects of the fires through the perspectives of those who survived them. The information can help identify the needs of residents living through the rebuilding process, and inform government agencies, local health care providers, nonprofit community groups, and others working to close gaps in disaster relief services.

The research may also benefit agencies and organizations working to reduce potential health impacts from future fire catastrophes, she said.

“By documenting the experiences of Californians during the fires and in their aftermath, we hope to bring those affected one step closer to full recovery,” she said.

Some possible toxic fuel sources from 2017’s urban wildfires: