Interrogating cancer:

Molecular Tumor Board looks for answers in tumor genomes

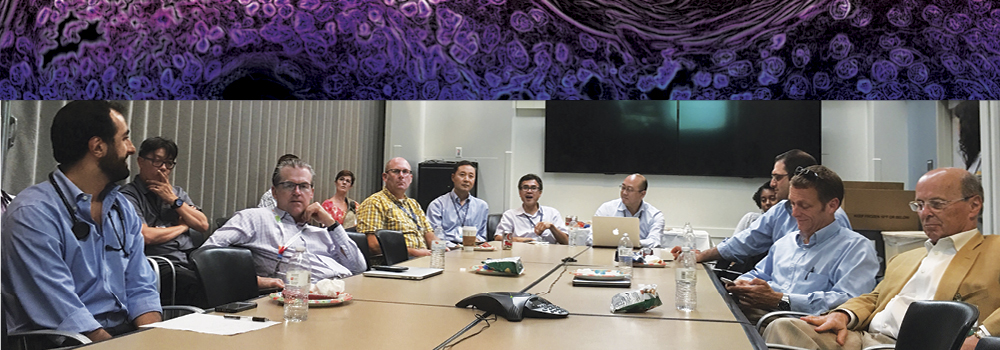

The group meets regularly around a large rectangular table: hematologists, oncologists, researchers, pathologists, geneticists

Joining the meeting by phone is a scientist from Foundation Medicine, the company that handles tumor sequencing for the cancer center and produces detailed reports about each patient’s cancer genome. It’s the basis for these discussions.

But knowing the mutations isn’t enough. The Molecular Tumor Board must transform that data into individual treatment plans, identifying the ideal combinations of drugs that will dial back a patient’s cancer. This is where leading-edge science meets patient care. They have a difficult job, assessing data from tumor genomes and choosing actionable mutations. The key word is actionable — genetic variations they can treat with targeted therapies.

The challenge of personalizing care

Tumor boards are nothing new. For decades these groups have met to select the best therapies for cancer patients. But with the emergence of next-generation sequencing, UC Davis and other cancer centers have added molecular tumor boards to the mix. The Foundation Medicine report starts the process.

“We look at almost all known cancer genes, analyze them and report the alterations and all the molecular information that’s pertinent to the alterations,” says Andreas Heilmann, biomedical informatics scientist at Foundation Medicine. “The clinical report describes the mutations, their role in that specific tumor type and, most importantly, the potential therapeutic options.”

The report produces an alphabet soup of genetic culprits: EGFR, ALK, RAS1, MET, BRAF, RET, ERBB2, mutated genes that have targeted therapies. If there are no FDA-approved drugs, the report will suggest clinical trials of drugs in development or a novel use or combination of existing drugs. Along with the mutations, board members discuss tumor type, location, stage, metastasis, patient history, family history and other factors.

But it’s not just connecting the dots between mutations and therapies. Genomes are complicated and cancer genomes doubly so. As tumors progress they become mutation machines, making it difficult to determine which variations are responsible for fueling cancer growth.

“We have to ask, is that mutation driving the cancer or is it just associated with the cancer?” says Karen Kelly, associate director for clinical research at the UC Davis Comprehensive Cancer Center.

This is the core issue in any molecular tumor board discussion. Targeting a driver mutation could slow the cancer, while hitting an associated variation — basically an artifact of tumor progression — might have no impact at all.

“Many of these patients have late-stage cancer,” says Kelly. “We have to do everything we can to make the right choices.”

A different angle on cancer

For centuries, tumors have been grouped by organ of origin: breast, lung, prostate, kidney. But lately scientists have discovered that mutations aren’t so particular.

“This is all about the molecular profile,” says Kelly. “Whether there’s a BRAF mutation in melanoma or a BRAF mutation in lung cancer, it’s still all about BRAF.”

Despite this emerging understanding of how mutations transcend tumor type, however, drugs are still approved the old-fashioned way. The BRAF inhibitor being used to fight melanoma may not be available for lung cancer, even if it does have the same mutation.

“That’s a frequent barrier,” notes Kelly. “We may have an FDA-approved drug for one cancer, but not for the one we’re trying to treat. We do everything we can to find a clinical trial.”

Patients in Northern California are particularly fortunate, as UC Davis, Stanford and UCSF are constantly conducting trials — and collaborating closely — to provide unique access to new treatments.

Molecular testing also can clarify the cancer of origin in ways traditional pathology cannot. Under a microscope, a tumor may look ambiguous, making it difficult to solidify a treatment plan.

“When we see a case where we’re not sure about the underlying cancer, we can sometimes use the molecular profile,” says Kelly. “One tumor we thought was skin cancer was clinically odd. But then we saw it had this specific mutational profile, which supported the initial diagnosis.”

A lot to learn

The Molecular Tumor Board has been meeting for over a year, and the effort seems to be paying off for patients. However, Kelly warns that more research must be done to fully gauge its effectiveness.

And other issues remain for investigation. Sometimes, even when given the appropriate inhibitors, patients do not respond to treatment.

“We know a lot about EGFR deletion 19,” Kelly offers as an example, “but there are still patients who don’t respond to EGFR inhibitors. We need to understand why some patients respond and others don’t. There’s still a lot to learn.”

Still, gathering tumor information is helpful. Foundation Medicine has created FoundationCORE, a database with tumor information from about 80,000 patients. The company has produced more than 135 peer-reviewed publications, gradually moving the science forward.

“Molecular tumor boards are an excellent opportunity for physicians to understand and apply this genomic information to their patients,” Kelly says. “We encourage all physicians to participate.”