UC Davis research settles the controversy over whether

naturally occurring asbestos causes cancer – now efforts can focus on preventing the diseaser

Exposure to asbestos in the workplace, particularly in shipyards, has long been recognized as a risk factor for mesothelioma, a rare form of cancer affecting the lining of the lung.

But does naturally occurring asbestos — found in rocks throughout California's Sierra Nevada, Coast Range and Klamath mountains — also pose a cancer risk?

UC Davis researchers recently completed the largest study to examine the question. Published in the American Journal of Respiratory and Critical Care Medicine, the study found that living near asbestos-containing rock is indeed associated with an increased risk of developing mesothelioma.

"Our findings indicate that the risks from exposure to naturally occurring asbestos, while low, are real and should be taken seriously," said Marc Schenker, professor and chair of the UC Davis Department of Public Health Sciences and the study's senior author.

"We hope public efforts will now shift to understanding the risk and how we can protect people from this preventable malignancy."

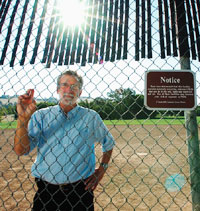

For the residents of western El Dorado County, an area of brisk housing development at the base of the Sierra foothills east of Sacramento, the UC Davis study had special relevance.

Many area residents had been alarmed by a U.S. Environmental Protection Agency study conducted in October 2004 at a popular park in El Dorado Hills, the county's largest town.

EPA investigators found that everyday outdoor activities — riding a bicycle, sliding into first base, swinging on a jungle gym — stirred up high concentrations of asbestos fibers in the air. Bicycling along the park's nature path kicked up the most fibers, generating concentrations 43 times greater than background levels.

Worried residents

"We want to know whether to continue to raise our 1 year old and our 3 year old here," a young mother told authorities at a community meeting the week the EPA study was released. Her comments appeared in one of the more than 90 articles about asbestos hazards in El Dorado County published by Sacramento Bee environmental writer Chris Bowman over the past seven years.

Against that backdrop, Schenker's study was front-page news in the Sacramento Bee on June 28, 2005 and again on July 13, 2005.

In the study, Schenker and his colleagues mined the California Cancer Registry for 2,908 cases of malignant mesothelioma diagnosed between 1988 and 1997 in adults ages 35 and older. The researchers also used the registry to identify a control group of ageand gender-matched pancreatic cancer cases (since pancreatic cancer has no known association to asbestos exposure).

One of the largest cancer databases in the world, the registry is responsible for collecting cancer incidence and mortality statistics, along with demographic data including address and occupational history, for more than one-tenth of the United States population. The registry's size allows researchers to identify associations that may not be apparent in smaller samples.

The researchers' next step was to pinpoint home or street addresses for every mesothelioma and pancreatic cancer case, using sophisticated geographic information system mapping. Residential distance from the nearest deposit of ultramafic rock, the predominant source of naturally occurring asbestos, was determined using a map from the California Department of Conservation, Division of Mines and Geology. The last step was to make statistical adjustments for sex, occupational asbestos exposure and age at diagnosis.

Proximity raises risk

The study showed that the risk of developing malignant mesothelioma was directly related to residential proximity to a source of ultramafic rock. Specifically, the odds of having mesothelioma fell by 6.3 percent for every 10 kilometers (about 6.2 miles) farther a person lived from the nearest asbestos source. The association was strongest in men, but was also seen in women. No such association showed up in the pancreatic cancer group. The overall mesothelioma rate was about one case per 100,000 people per year statewide.

Schenker's study was designed to find evidence of cause and effect, not determine the mesothelioma risk for any given individual. Future research will have to tackle that question.

But Laurel Beckett, professor and vice chair of the Department of Public Health Sciences and a study co-author, put the danger into some perspective. The risk of developing mesothelioma from exposure to naturally occurring asbestos, she said, is about the same as the risk of developing lung cancer from exposure to secondhand tobacco smoke.

Risk is dose-dependent

"Like smoking, exposure to asbestos appears to be very dose-dependent," Beckett added. "Day-in, day-out occupational asbestos exposures are more dangerous than intermittent exposures to naturally occurring asbestos in the community. But the more you can do to reduce your personal exposure, the safer you will be."

Schenker hopes the study will pave the way for research into how people can best protect themselves. Needed are studies to more accurately characterize which human activities are most likely to stir up asbestos fibers and to determine which types and sizes of fibers are most important to avoid, for starters.

"Because mesothelioma takes 20 to 30 years to develop, what we learn today will allow us to protect Californians from this preventable cancer decades into the future," Schenker said.