Better images for better outcomes

But the effort was worth it. In a country where most breast tumors are detected too late and where 50 percent of women with breast cancer die from their disease, the prospect of saving more lives was good motivation.

But the effort was worth it. In a country where most breast tumors are detected too late and where 50 percent of women with breast cancer die from their disease, the prospect of saving more lives was good motivation.

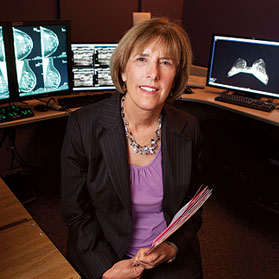

Karen Lindfors, professor of radiology and member of UC Davis Cancer Center, recently returned from a medical mission to Prishtina, capital of the Balkan republic, where she helped teach local doctors and technicians how to use the newly donated machine to screen women for breast cancer.

Lindfors says screening for breast cancer is very limited and, if available, done using ultrasound or old mammography machines that make it almost impossible to accurately detect lesions.

It was the second such trip for Lindfors through Radiology Mammography International, a nonprofit organization that provides technical assistance, donations and training in underserved parts of the world to support breast cancer prevention, detection and treatment. Lindfors made a similar trip to Macedonia in 2009.

In a country where most breast tumors are detected too late and where 50 percent of women with breast cancer die from their disease, the prospect of saving more lives was good motivation.

In a country where most breast tumors are detected too late and where 50 percent of women with breast cancer die from their disease, the prospect of saving more lives was good motivation.

Upon her return from Kosovo, Lindfors described what she saw as a system for breast cancer screening that lacks technological sophistication, clinical expertise and medical record management. Complicating matters, she says, is that patients don’t have health insurance; there are wide disparities when it comes to access to care; and radiologists in the public system earn less than $500 a month.

Lindfors says screening for breast cancer is very limited and, if available, done using ultrasound or old mammography machines that make it almost impossible to accurately detect lesions. Technicians are trained using textbooks – not in clinical practice. And because most patients are diagnosed late, they usually undergo full mastectomies rather than breast-sparing lumpectomies.

Because the clinics do not set up appointments for screening, Lindfors says, "it’s absolute chaos because everyone is trying to get in the door. Some patients waited three days for a screening."

Because the clinics do not set up appointments for screening, Lindfors says, "it’s absolute chaos because everyone is trying to get in the door. Some patients waited three days for a screening."

"What really struck me was how large the cancers were that we saw in Kosovar women who were sent in for evaluation, and how interested the radiologists were in really improving their skills," Lindfors says. "But what a tough road that is going to be because of the lack of infrastructure and support."

And because the clinics do not set up appointments for screening, Lindfors says, "it’s absolute chaos because everyone is trying to get in the door. Some patients waited three days for a screening."

In addition to daily lectures with medical personnel, Lindfors taught them how to do wire localizations, a procedure used to pinpoint breast lesions that are not palpable. She also worked with surgeons who performed the first wire-localized lumpectomy ever done in the country as well as the first sentinel lymph node biopsy.

All told, she says, in two weeks the team performed 200 mammograms and found seven cancers, five of which could be surgically removed with lumpectomy.

"What really struck me was how large the cancers were that we saw in Kosovar women who were sent in for evaluation, and how interested the radiologists were in really improving their skills."

"What really struck me was how large the cancers were that we saw in Kosovar women who were sent in for evaluation, and how interested the radiologists were in really improving their skills."

Lindfors says the challenge now is to keep the program sustainable in Kosovo, which requires government support and continued funding for supplies. She hopes to return to Kosovo some day, as long as those things are in place.

"I’ve received several positive e-mails from the radiologists I trained in Kosovo," Lindfors says. "They report reasonable progress on their breast cancer screening program. If that continues, I’ll return to Kosovo for a follow-up mission."