Nam K. Tran, PhD1; Chris Miller, PhD2; Sarah Waldman, MD3

1Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine; 2Center for Immunology and Infectious Diseases; 3Division of Infectious Diseases, Department of Internal Medicine

Introduction

The new SARS-CoV-2 mutant (VOC 202012/01) has become the dominant variant in the United Kingdom (UK)1 with the first known case in the United States identified on December 29, 2020.2 Over sixty percent of COVID-19 infections in the UK are now attributed to the new variant.1 The new variant is defined by 23 mutations, 13 of which are non-synonymous point mutations. In addition, there are 4 deletions and 6 synonymous point mutations.3,4 The non-synonymous mutations include a series of spike protein mutations, including a mutation in the receptor binding domain (RBD). Other notable mutations include a stop codon in ORF8. There are 6 synonymous mutations with 5 in ORF1ab (C913T, C5986T, C14676T, C15279T, C16176T), and one in the M gene (T26801C).

Viral mutations are not unexpected, this is an unusually large number of mutations in a single cluster. Mutations that enhance the virus’s capacity to spread among people provide a new variant with an advantage over the ancestral strain and enable the new variant to become dominant is its capacity to spread. In the case of SARS-CoV-2 VOC 202012/01, it is believed this RBD mutation increases the affinity of the S protein for the ACE-2 receptor on human cells which in turn enhances the transmissibility between people as any virus that a naïve person encounters is more likely to bind to its receptor.3,4 To date, there is no evidence that VOC 202012/01 increases COVID-19 severity.

However, the ability of some molecular diagnostic assays to detect the VOC may be affected by these mutations.5 Commercially available SARS-CoV-2 molecular assays often target the ORF region, as well as genes encoding for envelope protein (E), S and/or nucleoprotein (N). Therefore, the mutations in the new SARS VOC could theoretically impact the accuracy of assays that target ORF8 and S. However, as all commercial assays target two or more viral genes, the loss of ORF8 or S signal should not significantly affect assay performance. At present, three commercial assays target a combination of ORF8 or S with other targets.5,6 Assays targeting ORF8 and S are NOT used at UC Davis Health.

Laboratory Best Practice

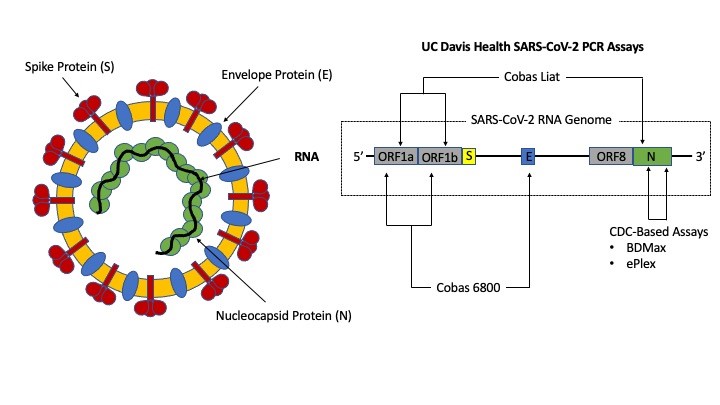

The new SARS-CoV-2 variant is detectable by the tests currently offered at UC Davis Health. Figure 1 identifies gene targets for the four UC Davis Health assays, all of which have received emergency use authorization (EUA) by United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) and is summarized here7-10:

- Our high throughput platform (Roche cobas 6800) targets the ORF1ab region and E gene,

- Our rapid point-of-care platform similarly targets the ORF1ab region, but also detects the N gene.

- Our medium throughput and “urgent” testing platforms used at UC Davis Health are based on the original Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) assay targeting two regions within the N gene (N1 and N2).

The selection of ORF1ab and N targets is due to their highly conserved nature (i.e., less likely to mutate) and their unique sequence specific for SARS-CoV-2. In contrast, the use of the E gene serves as a pan-Sarbecovirus marker.7 It must be noted that N and E mutations do exist but have not increased in prevalence since these variants appear to be no more infectious than non-mutants.

Situations may arise where only one out of two targets are detected. Detection of only one gene does not necessarily indicate the presence of a new variant and may be the result of low viral load. For example, with the high throughput assay at UC Davis Health, an ORF1ab positive, but E-gene negative result is still considered positive for SARS-CoV-2 RNA.7 It has been observed that ORF1ab positive/E-gene negative result combinations occur most frequently when patients are convalescing and present with very high cycle threshold (Ct) values suggestive of low viral loads. This phenomenon is due differing ratios of ORF1ab, and E genes produced during SARS-CoV-2 replication. Studies suggest ORF1ab and N sub-genomic material exist in higher quantities than E, thus, as patients recover, the E-gene RNA is the first to become undetectable. The same logic applies if encountering assays outside of UC Davis Health that relies on detecting ORF8 or S with other genetic targets (e.g., ORF1ab and/or N), thus not detecting ORF8 or S gene while detecting other targets does not necessarily indicate the patient is infected by the new SARS-CoV-2 variant. It must be noted that clinical laboratories do not report which genes are detected nor provide Ct-values for interpretation. The FDA has not approved this application at this time.

Presently, the only way to definitively identify the new SARS-CoV-2 variant is by sequencing. UC Davis is part of the SARS-CoV-2 Sequencing for Public Health Emergency Response, Epidemiology and Surveillance (SPHERES) program under the CDC, a national genomic consortium to monitor changes in the virus during the pandemic.11 Additionally, we have collaborated with University of California San Francisco and the Chan-Zuckerberg BioHub since March 2020 to sequence samples to monitor for changes locally. Suspected variants from clinical samples are sent to the California Department of Public Health Viral and Rickettsial Disease Laboratory (VDRL) in Richmond for sequencing.

References

- Center for Disease Control and Prevention, Interim: Implications of the Emerging SARS-CoV-2 Variant VOC 202012/01, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Washington Post article, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Public Health England –Investigation of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01 Technical Brief 1, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Public Health England –Investigation of novel SARS-CoV-2 variant: Variant of Concern 202012/01 Technical Brief 2, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- ThermoFisher Scientific website, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA) Emergency Use Authorization website, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Roche Molecular Systems cobas 6800/8800 SARS-CoV-2 assay information for use, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Roche Molecular Systems cobas Liat SARS-CoV-2 & Flu A/B assay information for use, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- GenMark ePlex SARS-CoV-2 assay information for use, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Beckton Dickenson BioGX SARS-CoV-2 assay information for use, Accessed on December 30, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention SPHERES Program website, Accessed on December 30, 2020.