New implant helps repair knee cartilage in UC Davis Health patients

Cassandra Lee is one of the first surgeons in the nation to use the CartiHeal™ Agili-C™ implant

A UC Davis Health orthopaedic surgeon is among the first in the U.S. to implant a new product that can help preserve knee cartilage. Cassandra Lee, a professor of orthopaedic surgery and chief of the Division of Sports Medicine, recently used CartiHeal™ Agili-C™ Cartilage Repair Implant to help ease a patient’s knee pain after an injury.

Cartilage, a connective tissue in the body, has no blood or nerve supply to nourish the growth of new tissues, and no innate ability to heal. CartiHeal™ Agili-C™ is an implant intended to repair damaged cartilage. It is absorbed by the body and is a new treatment option for patients.

“I am passionate about preserving and repairing tissue in knee joints and getting people back to what they love doing. This is a powerful tool that’s going to help a lot of people,” Lee said.

Lee’s first CartiHeal patient

Knee cartilage can tear through regular wear and tear, joint misalignment, kneecap dislocations, landing on or wrenching the knee, and other athletic injuries. Pieces of cartilage can shear off the joint or divots can develop from impact trauma.

Alicia McHatton developed pain in her left knee while hiking. McHatton is a neonatal Intensive Care Unit nurse at UC Davis Health. She’s a member of the transport team, helping to bring infants from remote or rural areas to UC Davis Children’s Hospital so they can get specialty care.

McHatton is a marathoner and has stayed active throughout her life, backpacking and hiking, often with her dog, Violet.

“My injury happened in July 2021,” McHatton explained. “It was nothing impactful; something just began to feel off and my knee swelled.” She had been having kneecap pain for years, but this felt different.

An MRI revealed that a sliver of cartilage torn from her left femur had wedged itself under her kneecap. During an arthroscopy, a minimally invasive surgical procedure, Lee discovered a second, larger defect. She extracted a bit of cartilage to perform a MACI (Matrix-induced autologous chondrocyte implantation) procedure: growing a sample of a patient’s own cartilage to later graft onto the damaged areas. While one of the MACI grafts took beautifully, the other did not, and McHatton’s knee still ached with every step.

As McHatton struggled to heal, Lee was checking on the availability of the CartiHeal Agili-C implant, which had recently received FDA approval. “Dr. Lee sent me all the research on CartiHeal, and I knew it was definitely something I wanted to try for the failed graft,” McHatton said.

Corals help with joint tissue repair

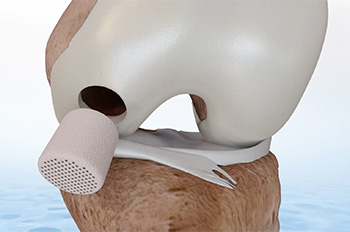

The CartiHeal implant is made from aragonite, a form of calcium carbonate derived from coral exoskeletons. The implants are porous, allowing infiltration by human tissue. The implant is made of inorganic materials that are generally well tolerated.

To repair McHatton’s wounded cartilage, Lee inserted the implant in the marrow of the femur, recessed to the level of the bone. As the implant is absorbed, stem cells and healing factors from the surrounding tissue and bone marrow migrate to the implant. This allows the damaged area to fill with new bone and cartilage. As McHatton’s knee continues to heal, the implant will be absorbed, leaving new tissue in its place.

CartiHeal implants are not intended to treat extensive injuries or severe arthritis.

“Because cartilage itself is such a specialized tissue, CartiHeal can’t exactly replace it,” Lee explained. “For patients who have cartilage injuries, multiple procedures may be needed, but if we can help push an eventual knee replacement further down the road with CartiHeal Agili-C, that’s going to be way better for their quality of life.”

Lee estimates that 40% of people over 40, and 25% of athletes, will have some form of cartilage defect within their lifetimes.

Post-op results

Six weeks after her operation with the implant, McHatton was doing physical therapy and performing squats and lunges.

Recovery and results depend on the implant location and vary for each patient, but McHatton felt ready to begin bearing weight on her leg within the first week. “Incredibly, she told me about a week post-op that the pain she had when initiating a step was just gone,” Lee said.

In comparison, after McHatton’s original MACI procedure she waited four weeks to allow the cartilage grafts to take before putting weight on her left leg.

I am passionate about preserving and regenerating tissue in knee joints and getting people back to what they love doing. This is a powerful tool that’s going to help a lot of people.” —Cassandra Lee, professor of orthopaedic surgery

McHatton isn’t quite ready to resume her outdoor activities, since patients who have had cartilage repair surgery may continue to heal for one to two years after the surgery. She’s already planning her next backpacking trip for when that time comes.