Residency Program - Case of the Month

February 2010 Final Diagnosis - Presented by Diane Sanders, M.D.

Answer:

Carcinosarcoma

Histologic description:

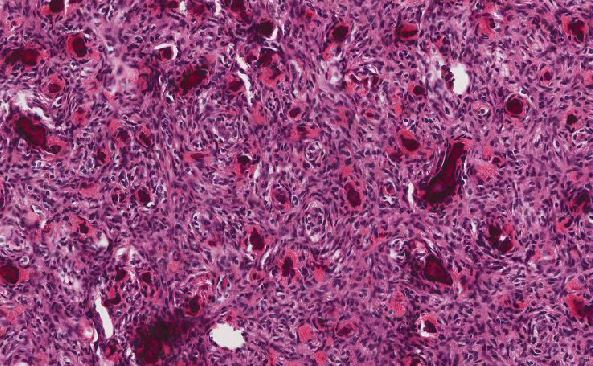

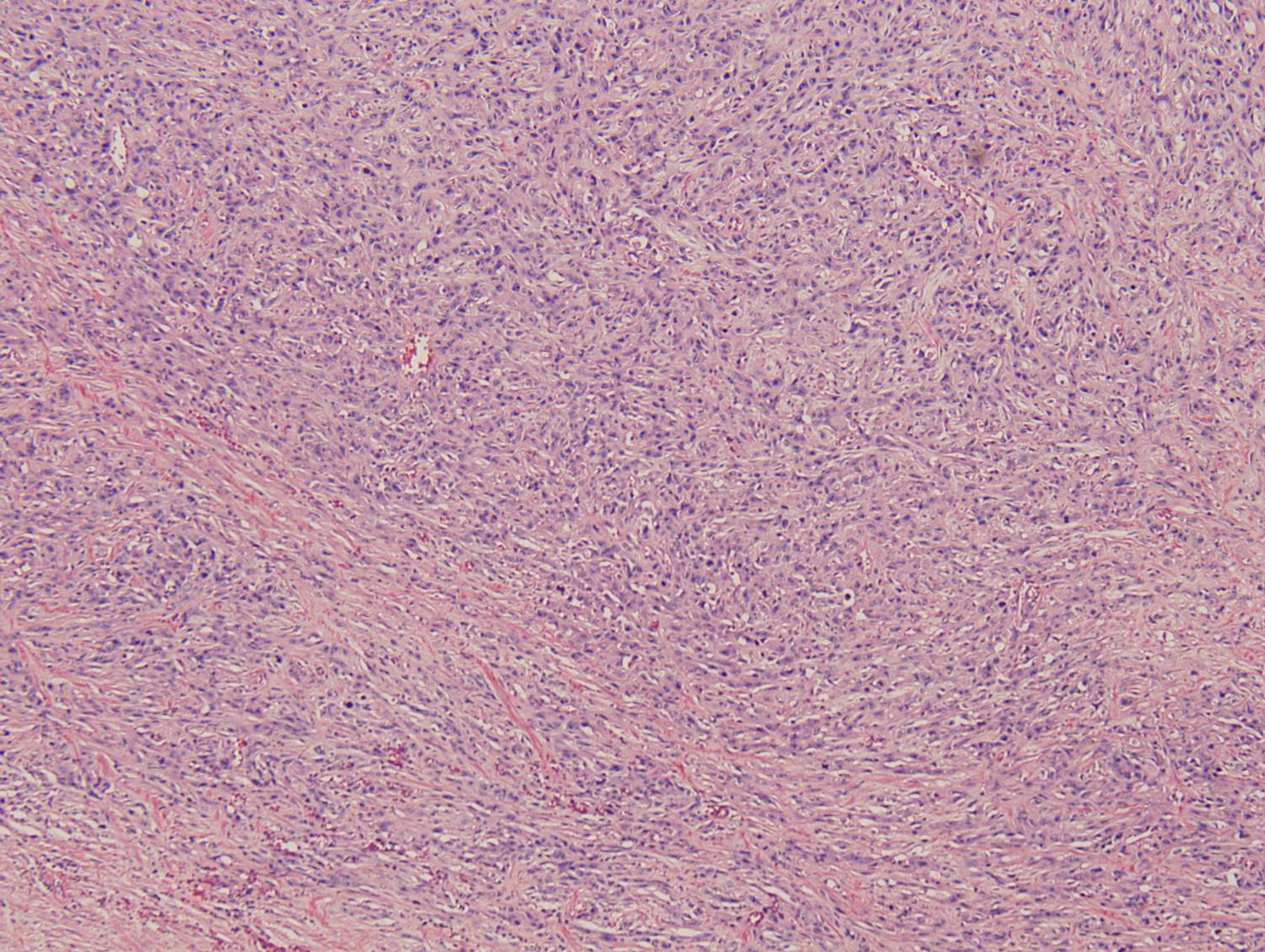

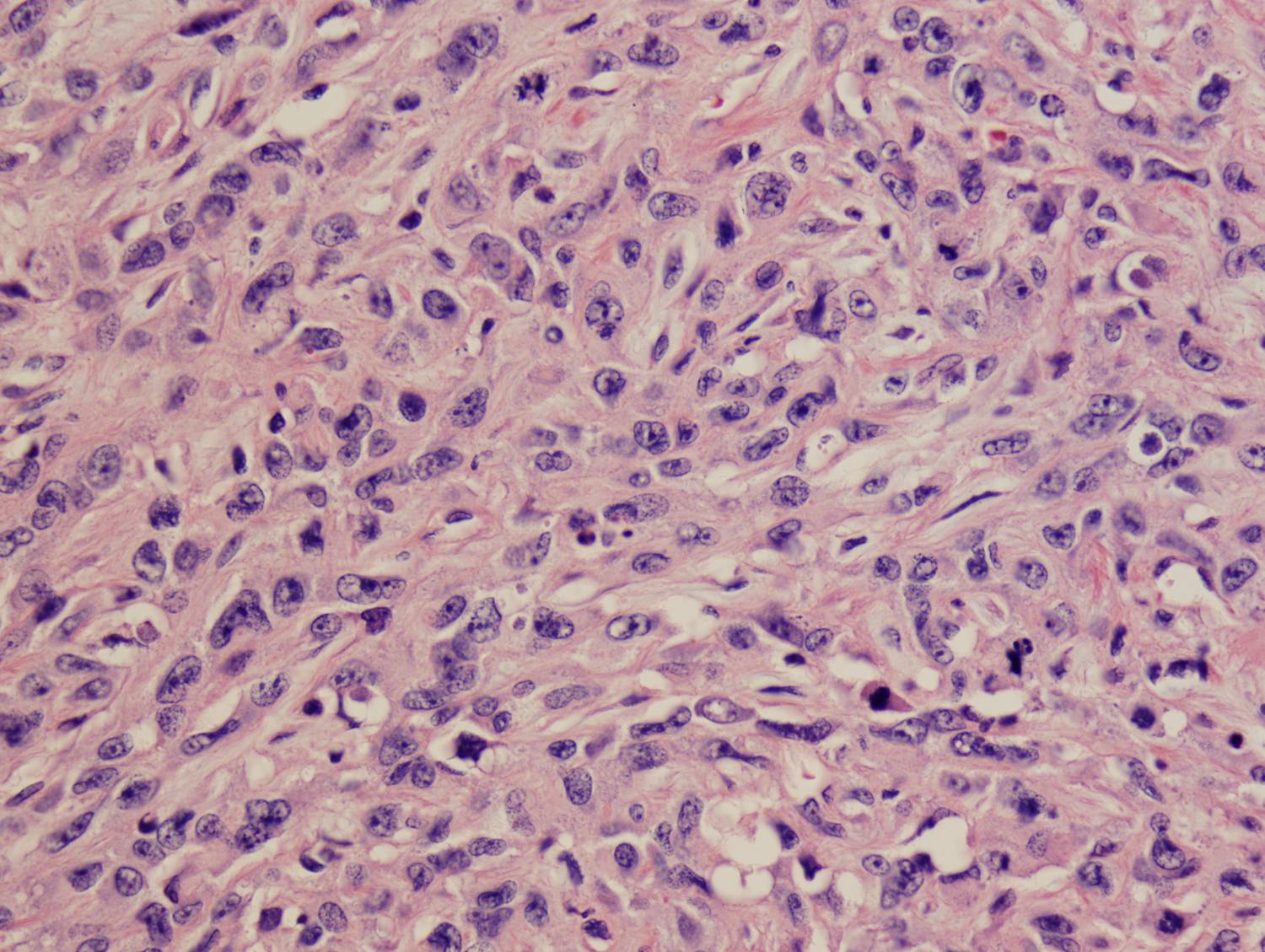

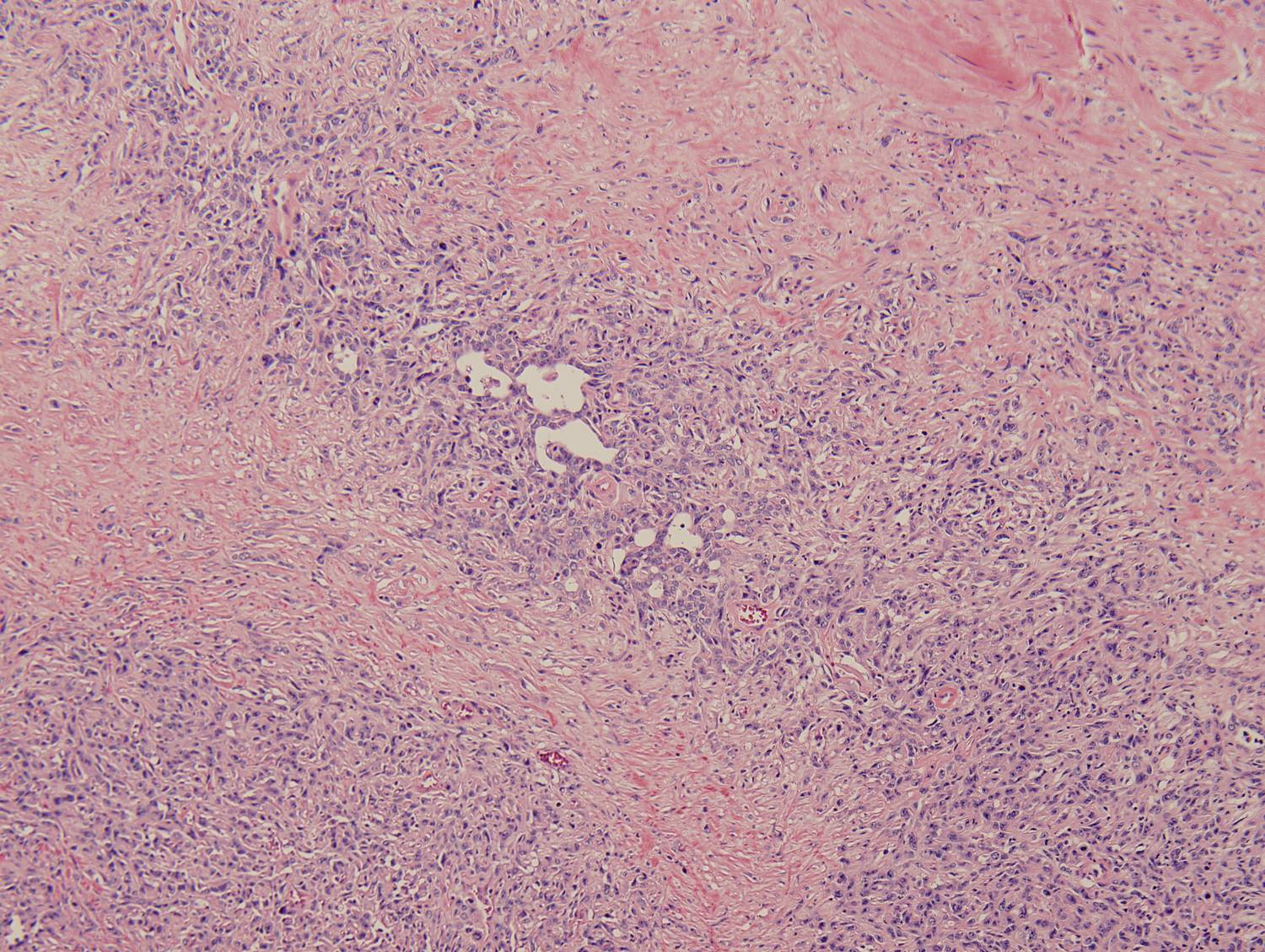

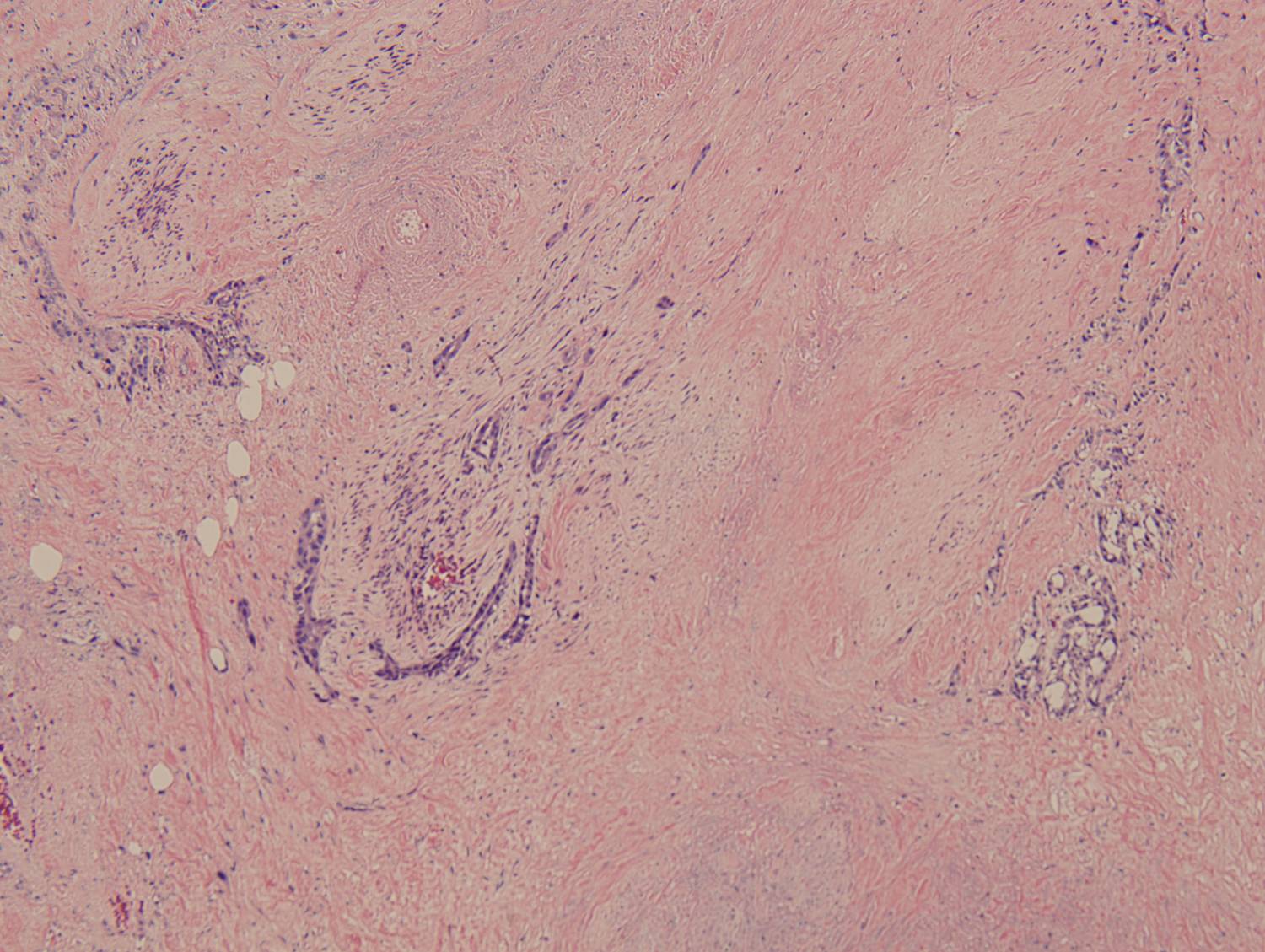

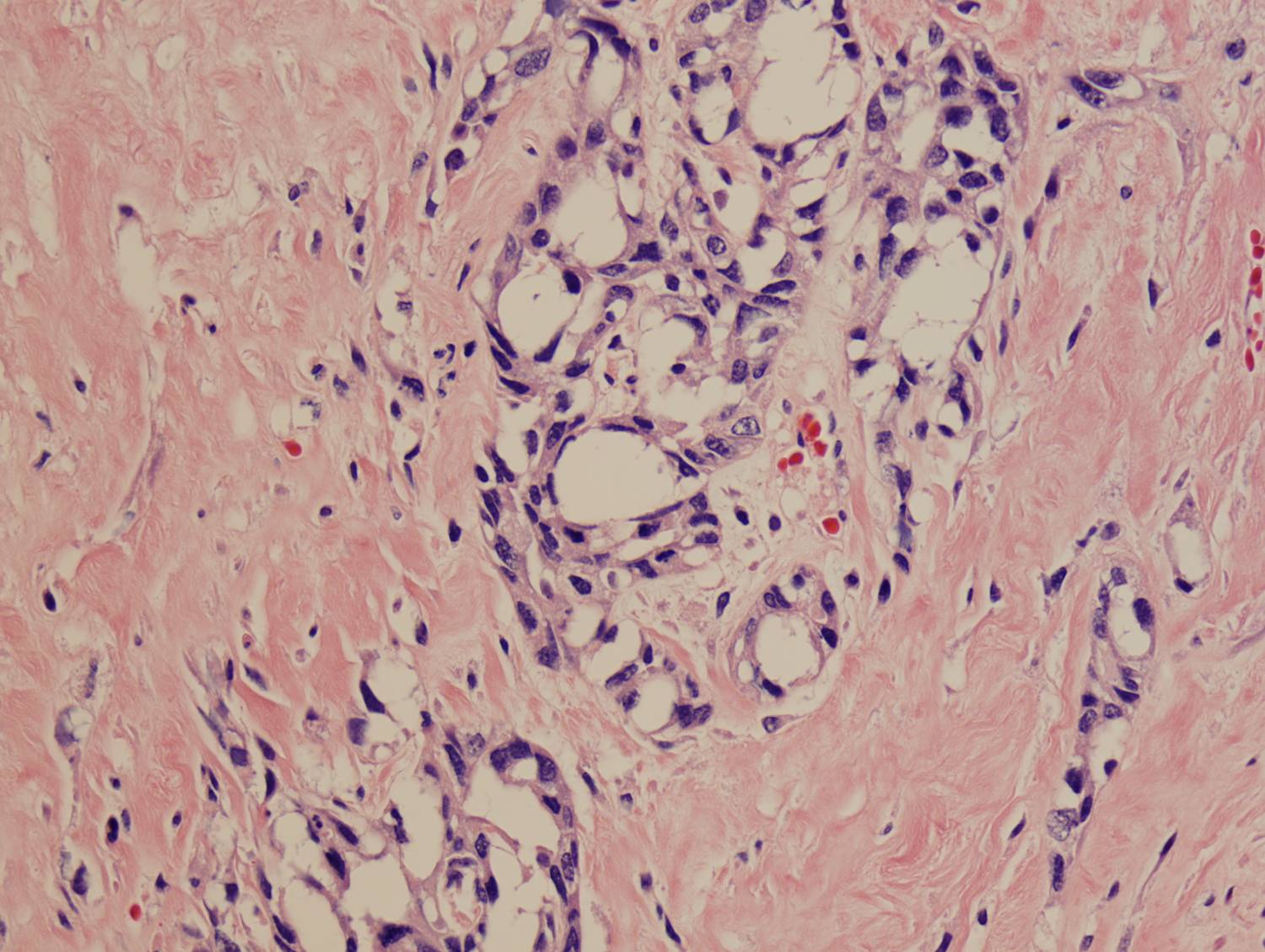

Histologic sections demonstrate a malignant neoplasm with a biphasic growth pattern. Both an epithelial component and a mesenchymal component are present. The majority of the tumor is composed of sarcomatous high grade spindle cells of varying sizes demonstrating abundant, finely granular cytoplasm and atypical, pleomorphic, round –to-elongated nuclei with irregular nuclear membranes, an open chromatin pattern and prominent nucleoli (Figures 1 and 2). Scattered mitotic figures are noted in these areas. In other areas, admixed within the spindled areas, there are glandular epithelial components identified (Figures 3 and 4). These areas are composed of glandular lumens lined by flattened cuboidal to columnar shaped cells with varied cytological appearances featuring small-to-intermediated sized pleomorphic nuclei of varying polarity with irregular nuclear membranes, an open, granular chromatin pattern and occasional prominent, large, deeply eosinophilic nucleoli. The cytoplasm of these atypical glandular cells varies from eosinophilic and finely granular to vesicular (Figure 5).

|

Figure 1: Low-power view showing an area of high grade spindle cells |

Figure 2: High-power view showing an area of high grade spindle cells |

|

Figure 3: Low-power view of glandular component |

Figure 4: Low-power view of an invasive glandular component with a surrounding desmoplastic response |

|

Figure 5: High-power view of glandular component |

|

Discussion:

Carcinosarcomas are defined by the World Health Organization (WHO) as tumors composed of intimately admixed malignant epithelial and mesenchymal elements. According to the WHO, the terminology sarcomatoid variant of urothelial carcinoma (with or without heterologous elements) should be used to describe biphasic neoplasms of the bladder with morphologic or immunohistochemical evidence of epithelial and mesenchymal differentiation. They also recognize use of the terms sarcomatoid carcinoma and carcinosarcoma for this tumor, although some series have referred to these two as separate entities. Some pathologists use "carcinosarcoma" only when heterologous mesenchymal elements are observed [1]. Others argue that histological differences like this have no clinical significance and believe the lesions are part of the same condition or are a spectrum of the same lesion [2, 3].

The histogenesis is a controversial topic and two theories have been proposed. The first is the convergence theory of multiclonal origin in which two stem cells, one epithelial and one mesenchymal, collide. If there are no common features on IHC or EM, this theory is favored. The second is the divergence theory of monoclonal origin which argues that the lesion develops as cell populations diverge from a single multipotent precursor. This theory seems to be gaining in popularity as molecular studies continue to show common shared genetic abnormalities between carcinomatous and sarcomatous elements. Loss of 9p (location of tumor suppressor p16) is the most consistent finding [4]. This theory is also supported by IHC and EM findings which demonstrate, respectively, immunoreactivity for cytokeratin or EMA in some mesenchymal areas and ultrastructural features of epithelial differentiation (desmosomes or tonofilaments) in some sarcomatoid areas [1, 4-6].

Most commonly identified in the female genital tract, carcinosarcomas of that location are termed malignant mixed müllerian tumors. Due to the prevalence of this location over other anatomic sites, it is seen as the prototypical clinicopathological setting for carcinosarcomas. In addition to the female genital tract, however, carcinosarcomas have been reported in the skin, gastrointestinal tract, hepatobiliary system, head and neck, respiratory system and urinary tract [5]. Within the bladder, carcinosarcomas are very rare. The exact incidence is not known [2]. Fewer than 100 cases have been reported in the literature [5, 7].

Epidemiologically, there is a slight male predominance and carcinosarcomas of the bladder typically occur in older individuals with a mean age of 66 years although they have been reported in patients ranging from 21 to 91 years old [1, 5]. These data are similar to those of conventional urothelial carcinoma; however carcinosarcomas of the bladder tend to behave more aggressively [5]. The risk factors are also similar to urothelial carcinoma and include smoking, male sex, 6th-7th decade of life, prior cyclophosphamide therapy and radiation to the pelvis [1-5, 7].

Grossly, the tumors are usually composed of a single large mass, up to 12 cm in greatest dimension. They are frequently well-circumscribed, exophytic, polypoid or nodular and display ulceration and necrosis [2, 5, 6].

Microscopically, they are composed of an epithelial component and mesenchymal component. The epithelial components most commonly present are urothelial carcinoma (most common), squamous cell carcinoma, adenocarcinoma and small cell carcinoma [1, 2, 7]. The mesenchymal component is usually composed of an undifferentiated high grade spindle cell neoplasm (most common), osteosarcoma, chondrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma, rhabdomyosarcoma, liposarcoma or angiosarcoma [1].

As would be expected, immunohistochemically, the epithelial components are most commonly positive for cytokeratins/EMA, CEA (adenocarcinoma), chromogranin and synaptophysin (small cell carcinoma) and negative for vimentin, SMA, desmin, calponin and caldesmon. The mesenchymal elements react with vimentin or specific markers corresponding to the mesenchymal differentiation such as desmin (rhabdomyosarcoma), SMA (leiomyosarcoma), S100 (MPNST, chondrosarcoma), CD31 (angiosarcoma), calponin (fibrosarcoma, leiomyosarcoma) and caldesmon (leiomyosarcoma) [1, 2].

The differential diagnosis of these tumors includes a primary sarcoma; however this is very rare and would not demonstrate malignant epithelial elements, staining for epithelial markers or ultrastructural evidence of desmosomes or tonofilaments [3, 5]. A sarcoma with pseudoepitheliomatous hyperplasia could be considered, however in these lesions, there is a less intimate association between the two components and there is a more distinct interface between the malignant sarcomatous elements and hyperplastic epithelial elements [5]. In lesions lacking atypia and mitotic figures within the sarcomatous areas, urothelial carcinoma with benign osseous or cartilaginous metaplasia could be considered [1, 2]. Spindle cell melanoma should also be considered and should demonstrate HMB-45 and S100 staining and contain melanin [2]. Other entities to consider would include teratomas, however these would require features from all three embryologic layers and they usually have abundant benign epidermoid elements and dermal adnexal structures [5]. Pseudosarcomatous proliferations should also be considered. These would demonstrate minimal reactive atypia and atypical mitotic figures would be absent. A carcinoma with pseudosarcomatous stroma could be considered as well as other forms of pseudosarcomatous proliferations, including inflammatory myofibroblastic tumors and post-operative spindle cell nodules [1, 5]. Along with the lack atypical mitotic figures and the minimal reactive atypia, post-operative spindle cell nodules demonstrate slit-like vessel proliferation and commonly have myxoid areas as well [1, 5]. Finally, metastatic disease should also be considered [1].

With respect to prognosis, it is based on the stage at diagnosis [5]. Patients with carcinosarcoma usually present with a high stage malignancy [2]. In studies that provided clinical follow-up, approximately half of the patients died within 1 year of the diagnosis [5].

Due to the low incidence and lack of large multi-institutional series, well-established treatment and surveillance protocols are lacking. The majority of patients in the literature underwent a radical cystectomy as a single therapeutic modality. Other patients underwent surgical treatment followed by radiation, chemotherapy or some combination of both [5, 2]. A small number of patients experienced prolonged survival when treated with a radical cystectomy and adjuvant radiotherapy [2].

References:

- Sauter, G. WHO Classification of Tumours: Pathology and Genetics of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs. International Agency for Research on Cancer, 2004.

- Lopez-Beltran, A. et al. Carcinosarcoma and Sarcomatoid Carcinoma of the Bladder: Clinicopathological Study of 41 Cases. The Journal of Urology. Volume 159, Issue 5. May 1998: 1497-1503.

- Mills, S. Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 4th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins, 2004.

- Mukhopadhyay, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the Urinary Bladder Following Cyclophosphamide Therapy. Evidence for Monoclonal Origin and Chromosome 9p Allelic Loss. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine: 2004. Vol. 128, No. 1: e8-e11.

- Baschinsky, et al. Carcinosarcoma of the Urinary Bladder—An Aggressive Tumor With Diverse Histogenesis. A Clinicopathologic Study of 4 Cases and Review of the Literature. Archives of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine: 2000. Vol. 124, No. 8: 1172–1178.

- Rosai, J. Surgical Pathology, 9th ed. New York: Mosby, 2004.

- Maestroni, U. et al. Bladder Carcinosarcoma: a case observation. Acta Bio Medica Ateneo Parmense: 2004. Vol. 75, 74-76.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director