Residency Program - Case of the Month

September 2010 Final Diagnosis - Presented by Heidi Jess, M.D.

Answer:

Low grade neuroendocrine carcinoma within a sacrococcygeal teratoma

Histologic description

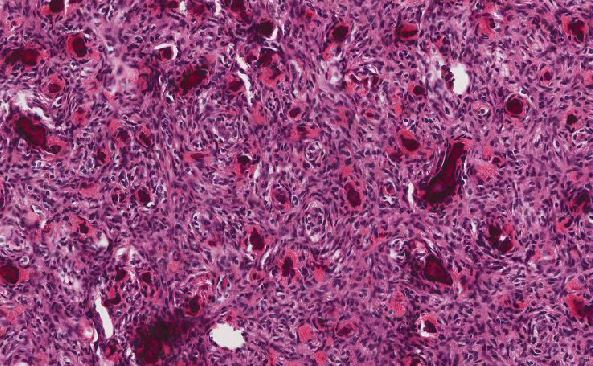

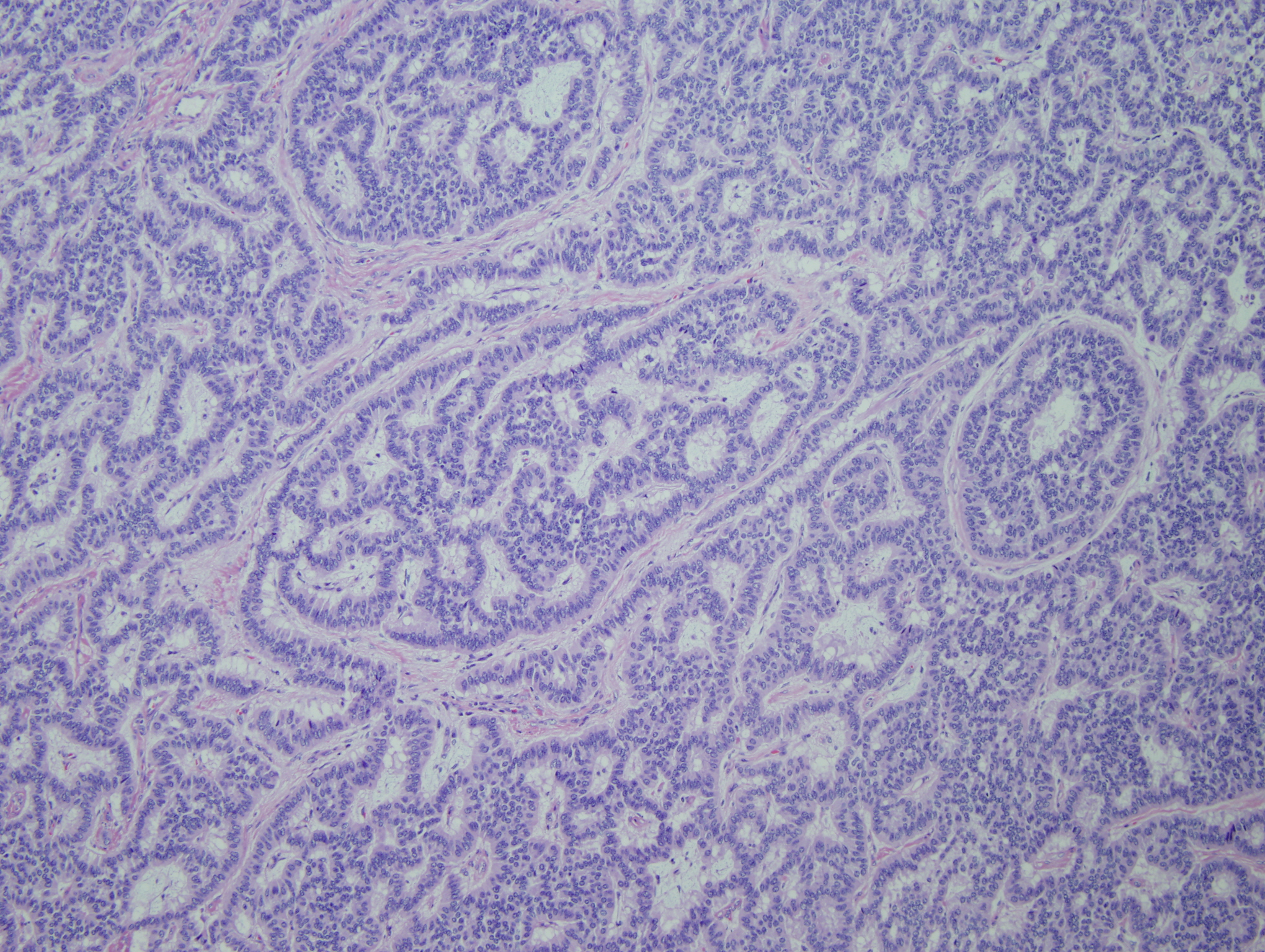

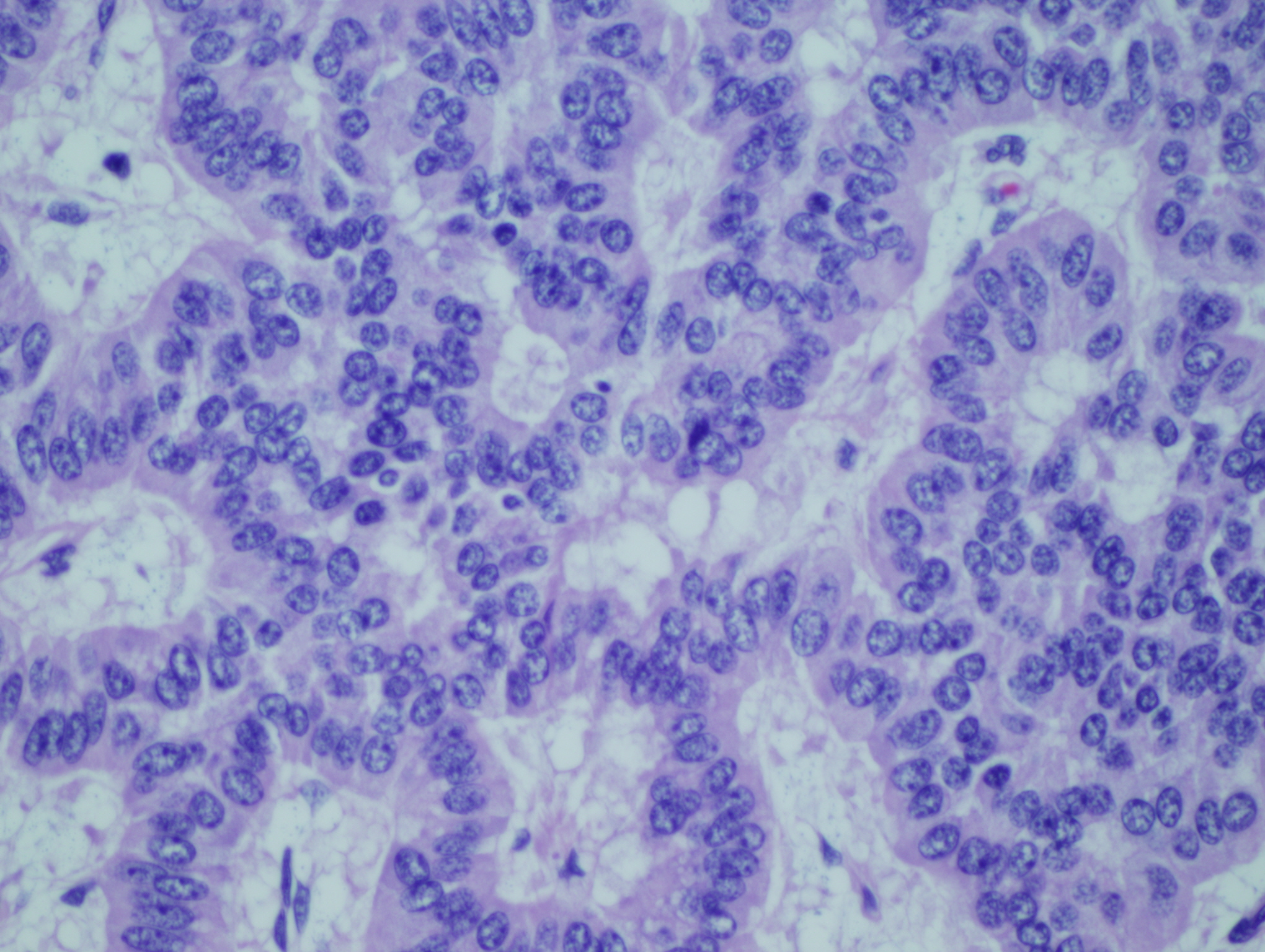

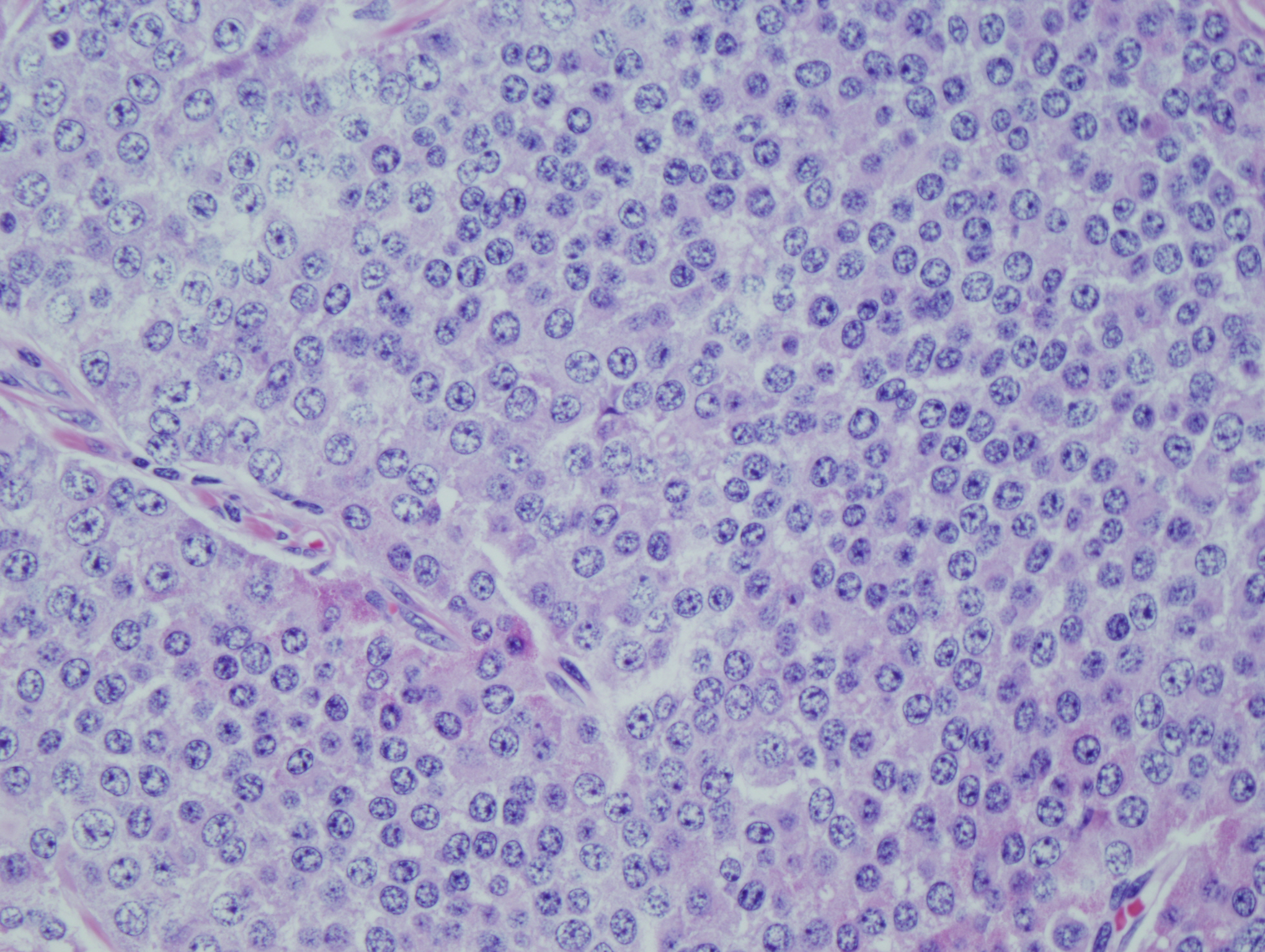

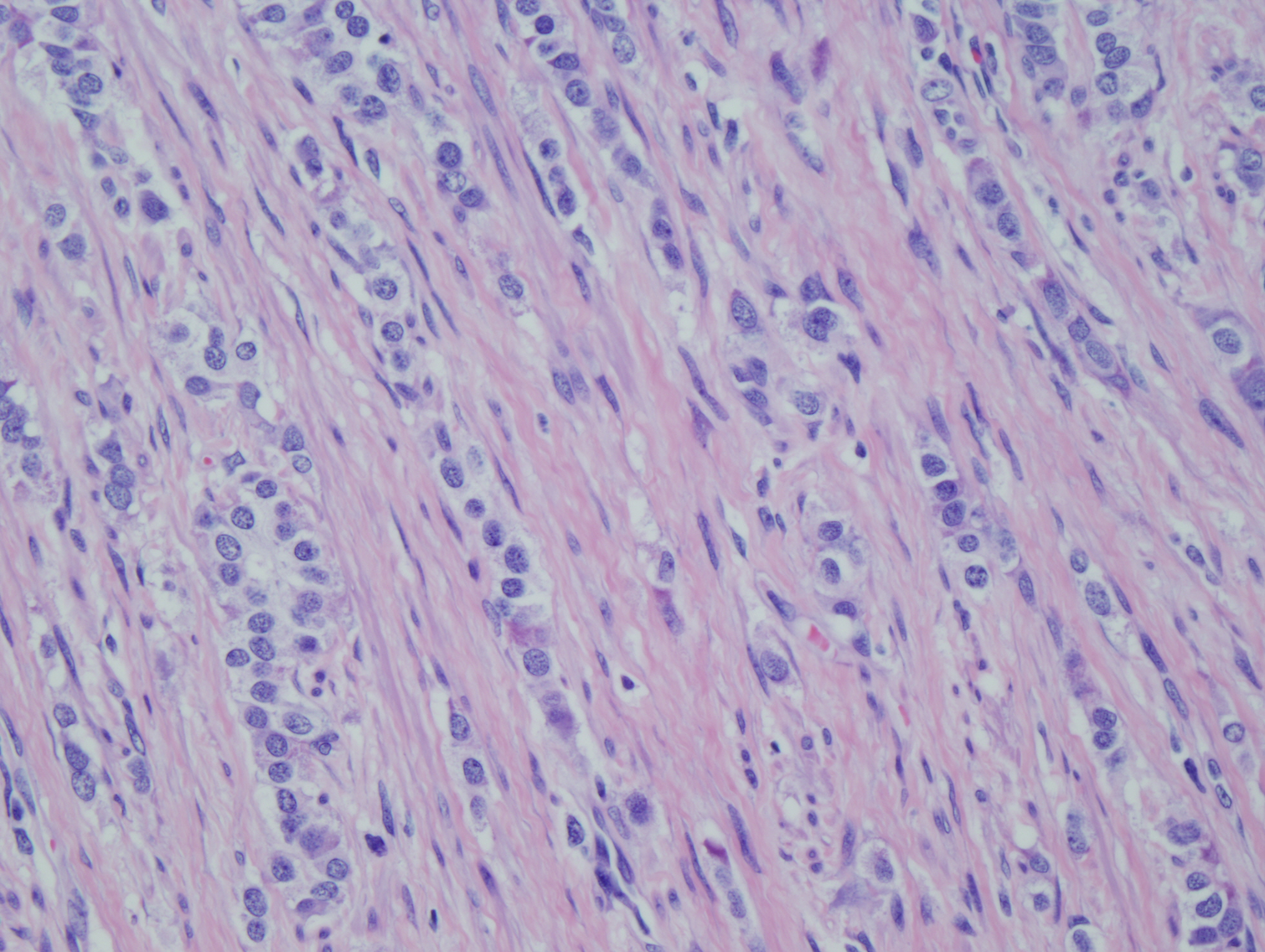

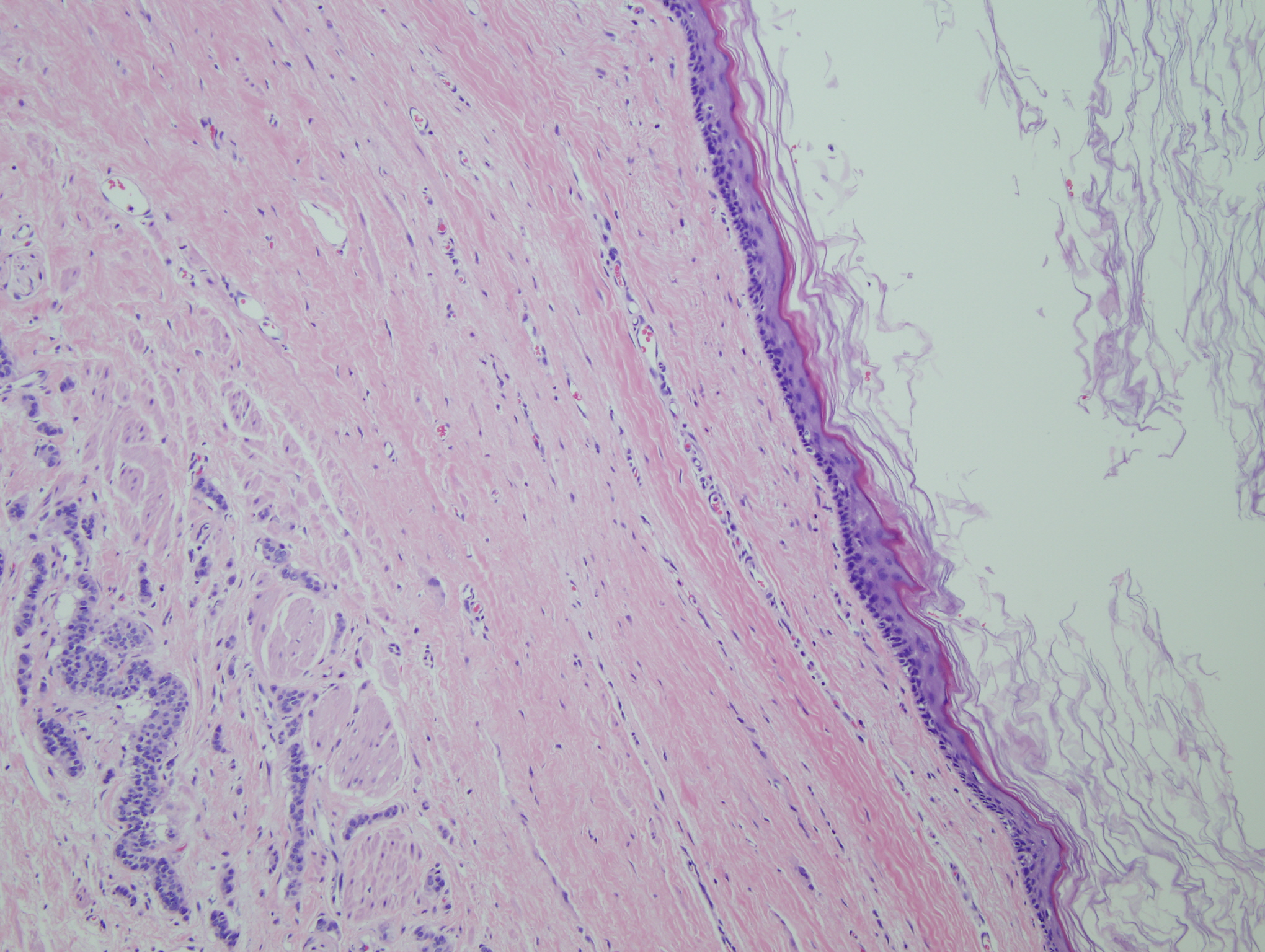

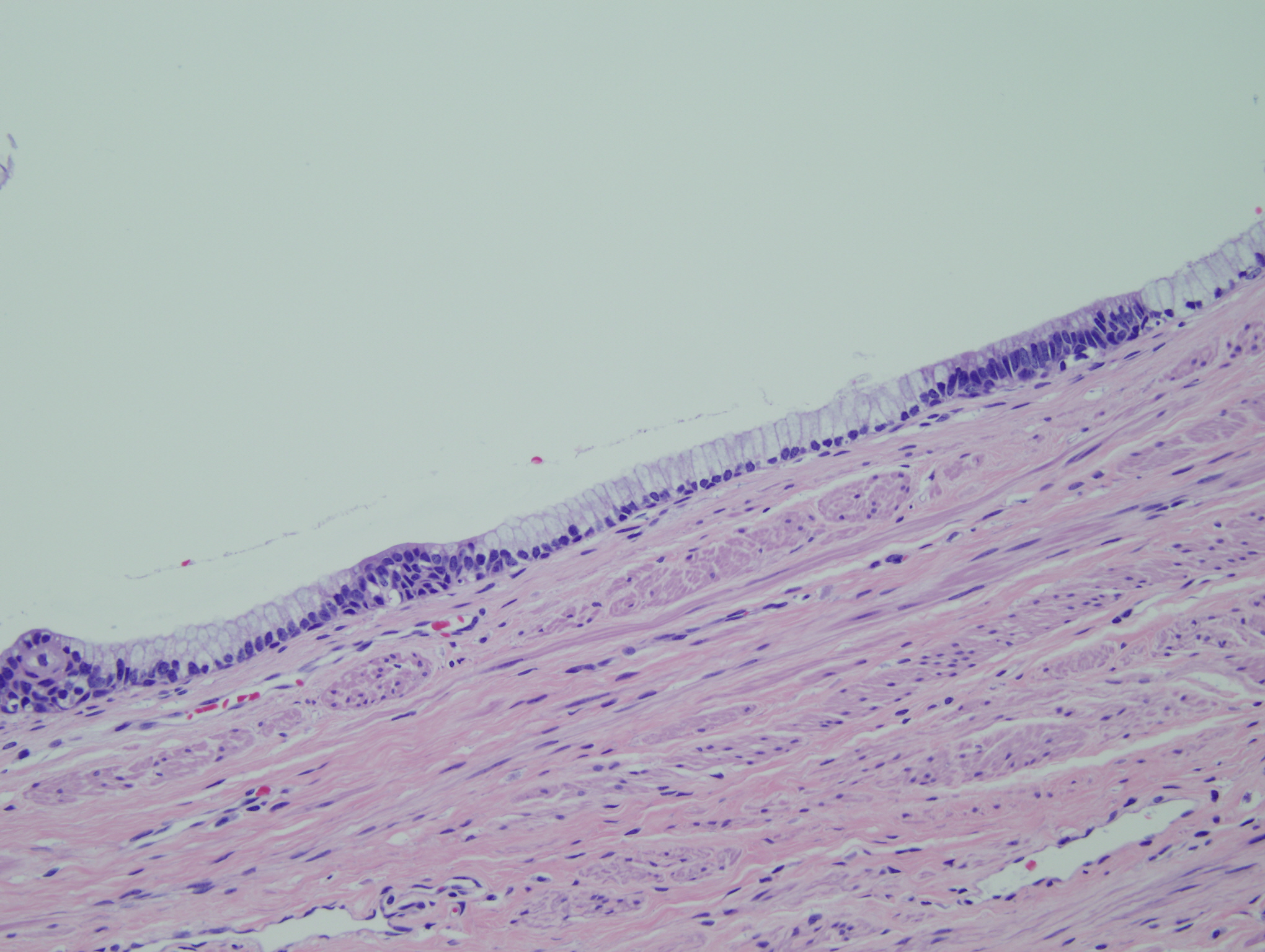

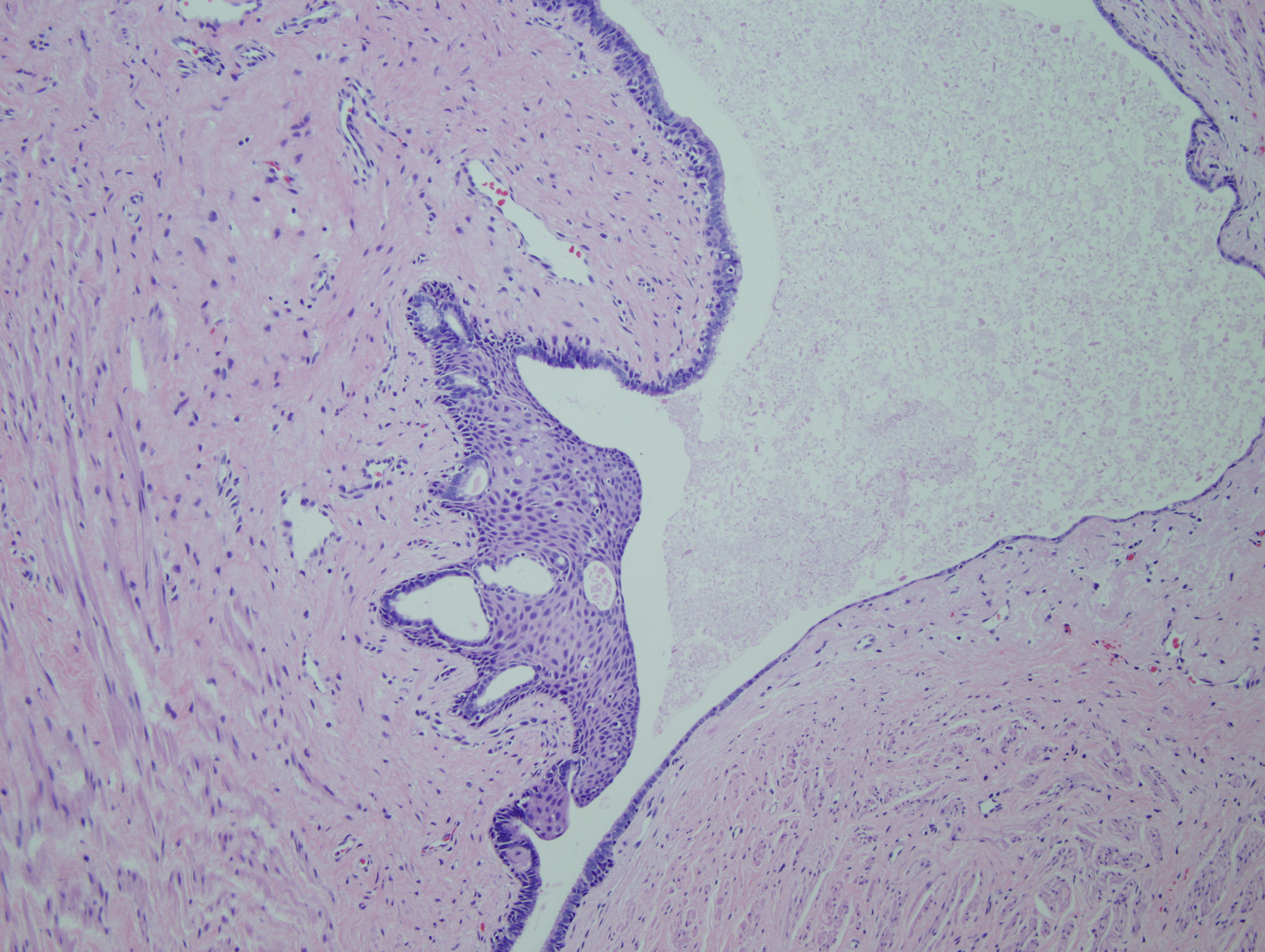

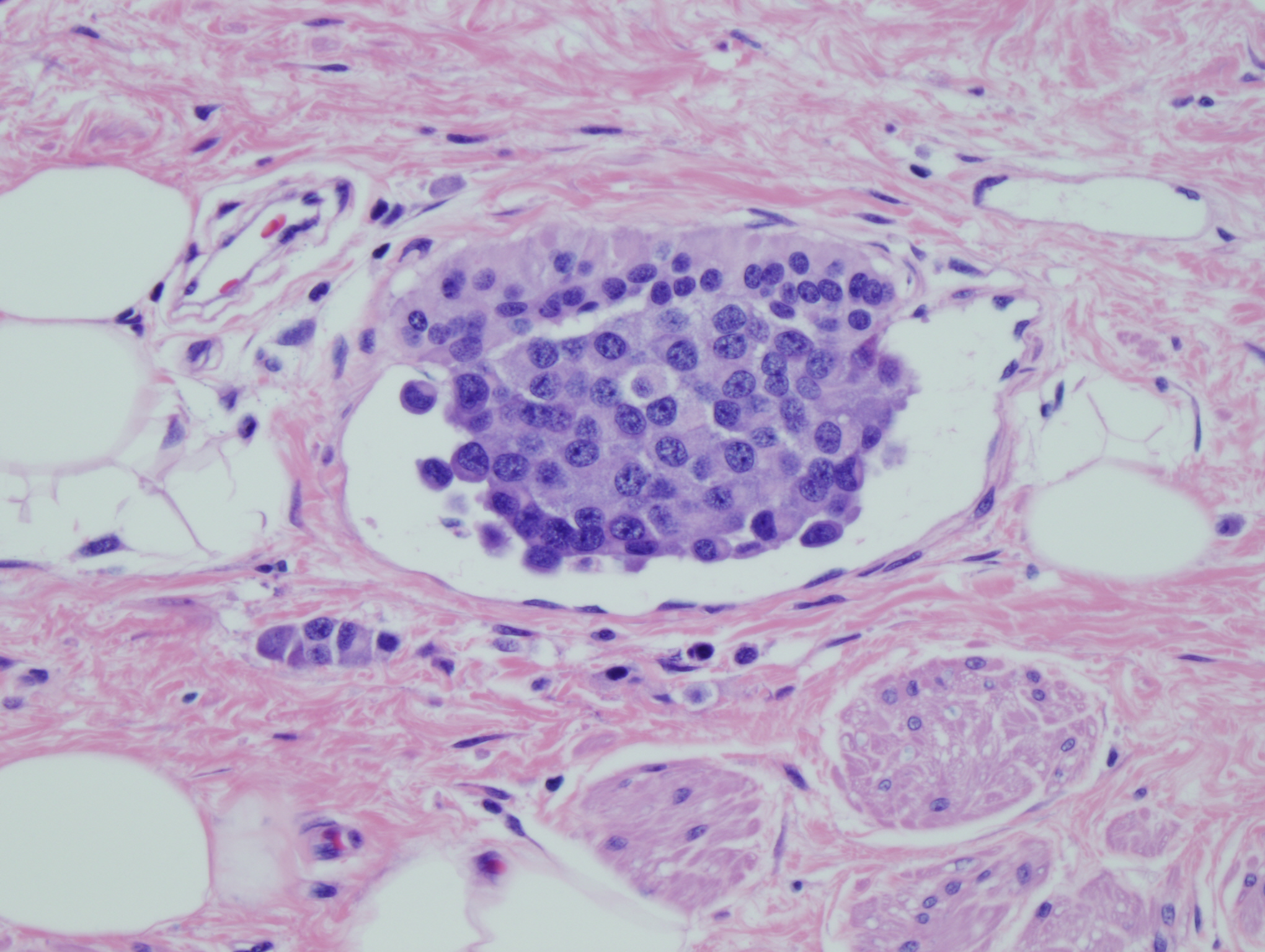

The sacrococcygeal soft tissue mass consisted predominantly of mature teratoma elements (Figures 6-8). Within the teratoma there were firm tan nodules measuring 2.5 cm in greatest dimension (Figures 1-5). Histology of the tan nodules revealed neoplastic cells with moderate nuclear to cytoplasmic ratios and finely clumped "salt and pepper" chromatin (Figure 4). Some of the cells had a prominent nucleolus. These cells are arranged in a predominantly trabecular pattern (Figures 1-3). Areas within the nodules also showed solid growth (Figure 4) and infiltrating single strands (Figure 5). Lymphovascular invasion was identified (Figure 9).

|

Figure 1: Neoplastic cells in a trabecular pattern adjacent to mature teratoma |

Figure 2: Fibrous trabecular pattern with anastomosing bands of tumor cells |

|

Figure 3: Trabecular pattern |

Figure 4: Neoplastic cells with moderate N:C ratio, eosinophilic cytoplasm, finely clumped chromatin and prominent nucleolus in a solid growth pattern |

|

Figure 5: Infiltrating tumor cells in single strands |

Figure 6: Neoplastic cells in infiltrating stands adjacent to squamous lined cystic component of mature teratoma |

|

Figure 7: Mature teratoma cystic component lined by bland mucinous cells |

Figure 8: Mature teratoma with mucinous cyst with focal squamous differentiation

|

|

Figure 9: Lymphovascular invasion |

|

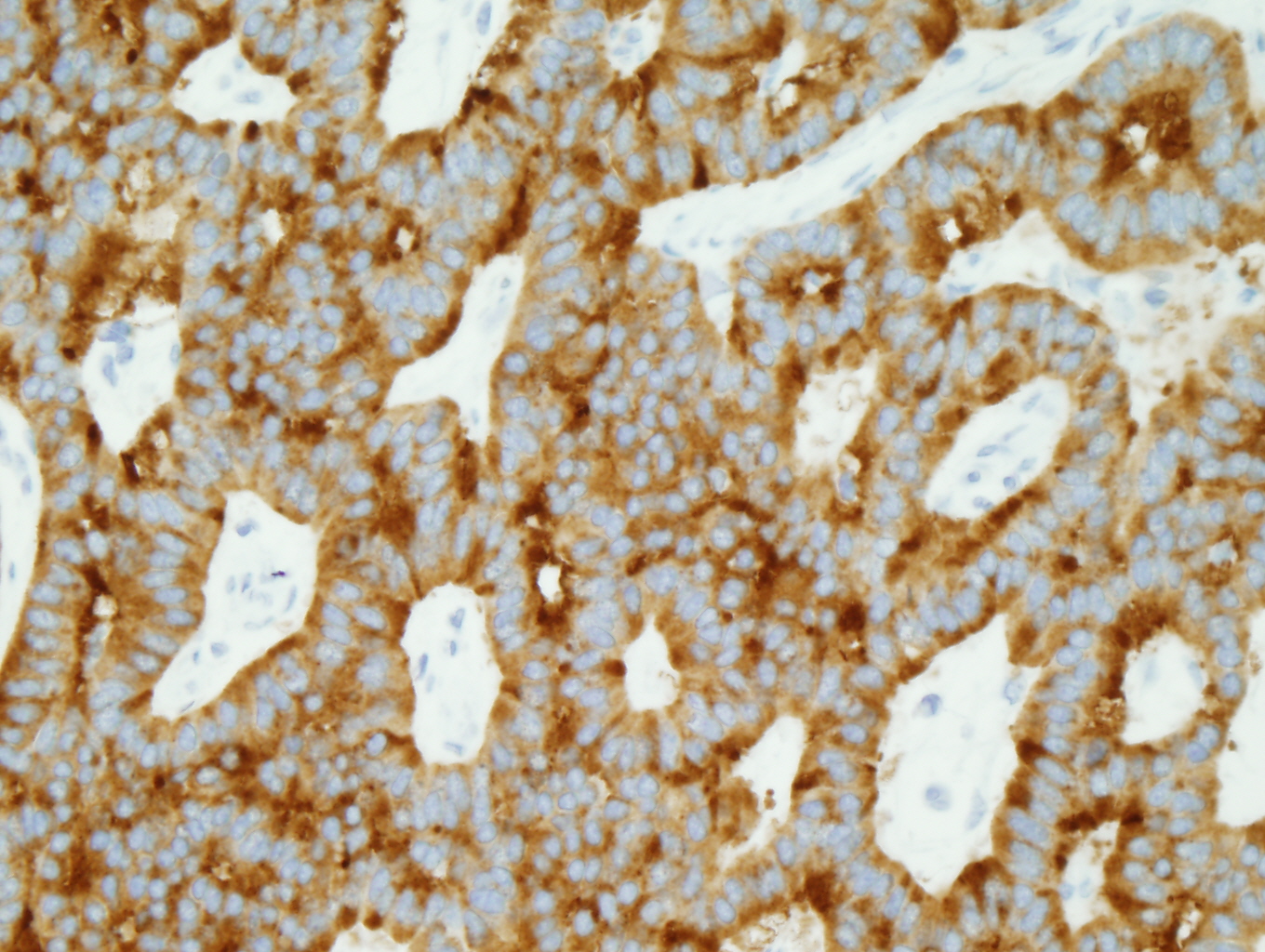

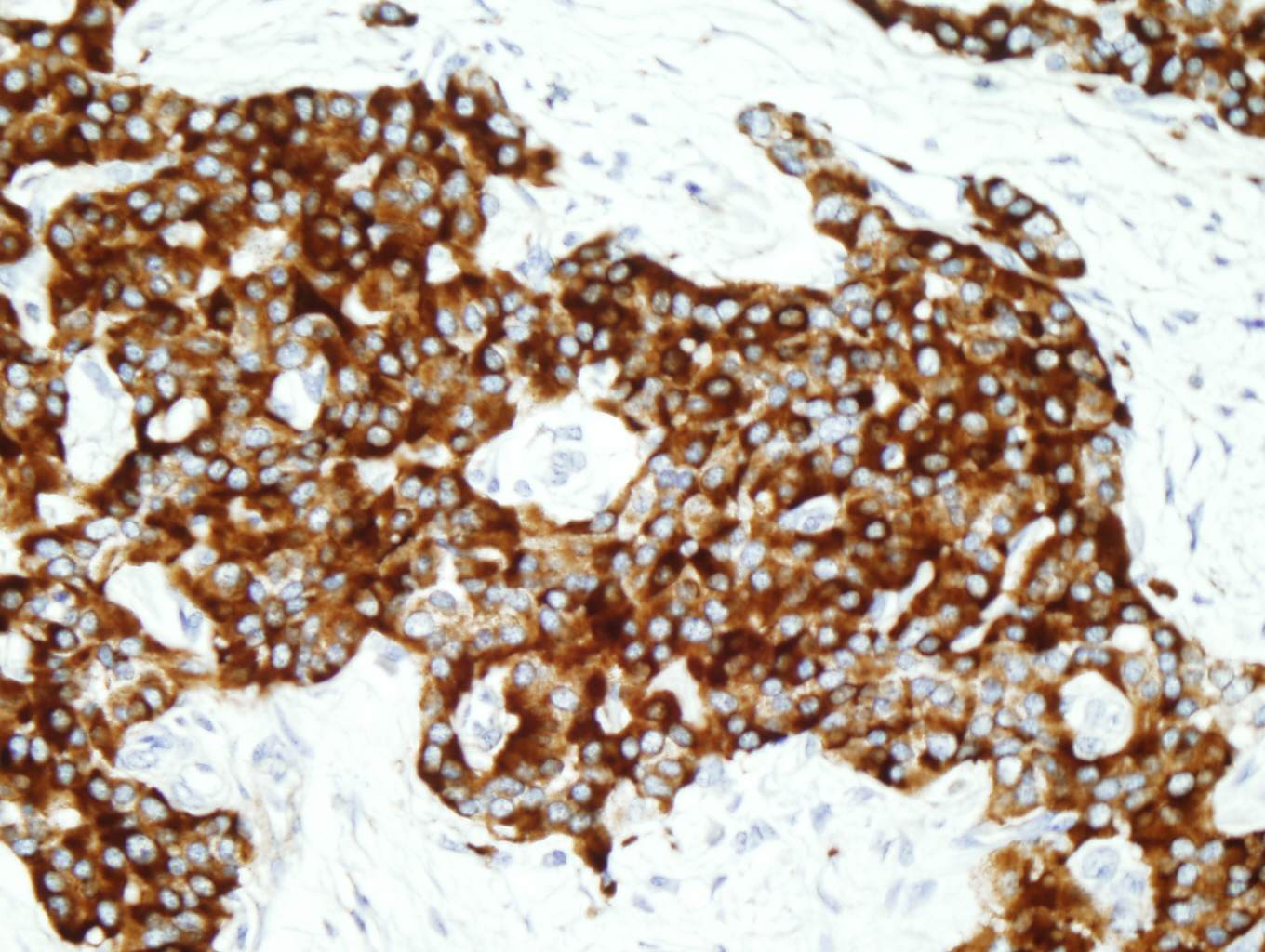

Immunohistochemistry

|

Figure 10: AE1/AE3 positive |

Figure 11: Synaptophysin positive |

|

Figure 12: Trabecular pattern |

|

Discussion:

Tumors within the presacral space and sacrococcygeal area are uncommon tumors with an incidence of 1:40,000. Approximately 45-50% of presacral masses are malignant or have areas of malignant change within them (4). Teratomas within the presacral space most commonly occur in infancy and have an incidence of 1 in 30,000-43,000 live births with a 3-4:1 female-to-male ratio (2,4,7). Sacrococcygeal teratomas in adults are very rare (2,7). Patients with sacrococcygeal teratomas most often are asymptomatic. If symptoms are present, they are often reflective of the tumor size, mass effect and infection which may result in nerve compression with paresis or paresthesias, bladder dysfunction and constipation (1,4).

Macroscopically, teratomas are partially cystic masses filled with gelatinous fluid or keratin. Microscopically, they contain a variety of cell types derived from more than one germ layer. Teratomas can be classified into three histologic categories: mature, immature, and malignant. Mature teratomas have benign epithelial-lined cysts, mature cartilage and/or muscle. Immature teratomas contain primitive mesoderm, endoderm or ectoderm admixed with the mature elements. Malignant teratomas contain frank malignant tissue which may or may not be of germ cell origin (7).

Carcinoid tumors within the presacral space are rare and most often represent direct extension or metastatic spread from adjacent rectal carcinoids (4,5). Dujardin et al found 20 cases of primary neuroendocrine carcinoma in the presacral space reported in the literature in 2009. Nine of the cases were associated with a tailgut cyst and three originated from a sacrococcygeal teratoma (3).

The majority of teratomas are benign and the treatment consists of complete surgical resection (4,7). If the lesion is not completely removed, the tumor may recur locally. In addition, studies have shown that failure to remove the coccyx has been associated with a high risk of recurrence, due to potential nidus of totipotential cells within the coccyx (2,7). There is a 1-12% risk of malignant transformation in adult patients (1). For malignant teratomas, additional treatment with chemotherapy and/or radiation is recommended (7). Due to the rarity of sacrococcygeal teratomas, standard recommendations for chemotherapy and radiation have not been defined. The prognosis of mature teratoma is good while malignant teratoma is poor with a higher tendency to recur and metastasize (2,7). The overall 5 year survival rate for presacral neuroendocrine carcinoma with metastisis has been reported to be 20-30% (3).

The differential diagnosis of sacrococcygeal teratoma includes tail gut cyst, chordoma, menigocele, neurofibroma, fibrosarcoma, giant cell tumor of sacrum, pilonidal cysts, sacral osteomyelitis, fistula or abscess formation, granuloma and tuberculosis (2,7). Malignant components within a teratoma need to be differentiated from primary and metastatic tumors. Colonoscopy and other imaging modalities are required to differentiate between primary presacral carcinoid and metastasis.

References:

- Afuwape et al, Adult Sacrococcygeal Teratoma: A Case Report, Ghana Medical Journal, Vol 43, No 1, March 2009.

- Arazi et al, Primary Neuroendocrine Carcinoma Arising Within a Mature Sacrococcygeal Teratoma, Orthopedics, Vol 30, No 10, Oct 2007.

- Dujardin et al, Primary neuroendocrine tumor of the sacrum: case report and review of the literature, Skeletal Radiol, No 38, 2009.

- Ghosh et al, Presacral tumors in adults, Royal Colleges of Surgeons of Edinburg and Ireland, Vol 5, No 1, 2007.

- Luong et al, Presacral carcinoid tumour, Review of the literature and report of a clinically malignant case, Digestive and Liver Dsiease, No 37, 2005.

- Mills et al, Sternberg's Diagnostic Surgical Pathology, 5th ed, 2010.

- Ng et al, Sacrococcygeal Teratoma in Adults, Cancer, Vol 86, No 7, Oct 1999.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director