Residency Program - Case of the Month

December 2010 - Presented by Melissa Rodgers-Ohlau, M.D.

Answer:

Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH)

Additonal Lab Results:

Triglycerides – 538 (normal: 35-160 mg/dl)

Ferritin – 1701 (normal: 10-291 ng/ml)

Normal to decreased fibrinogen

Histologic description

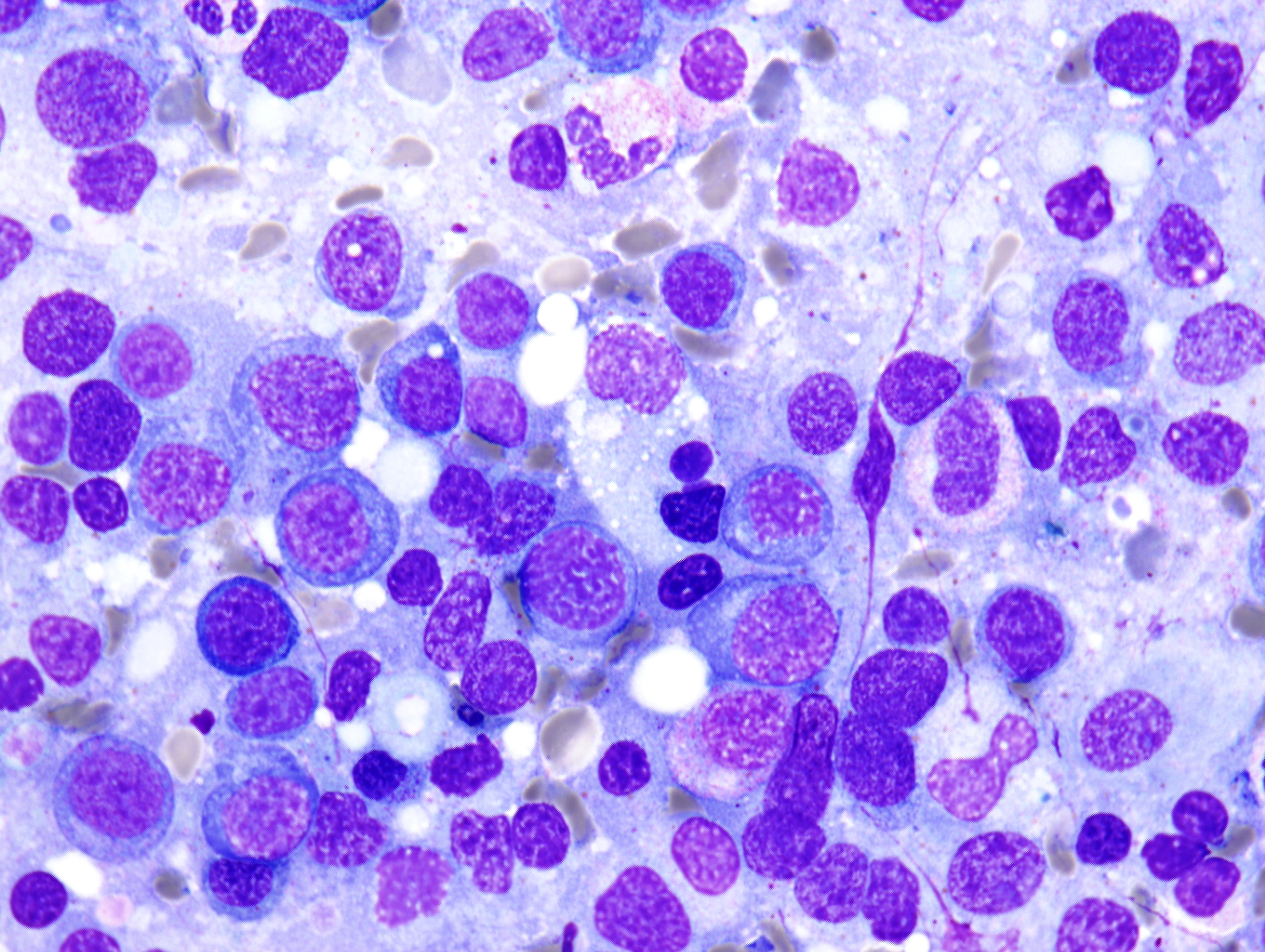

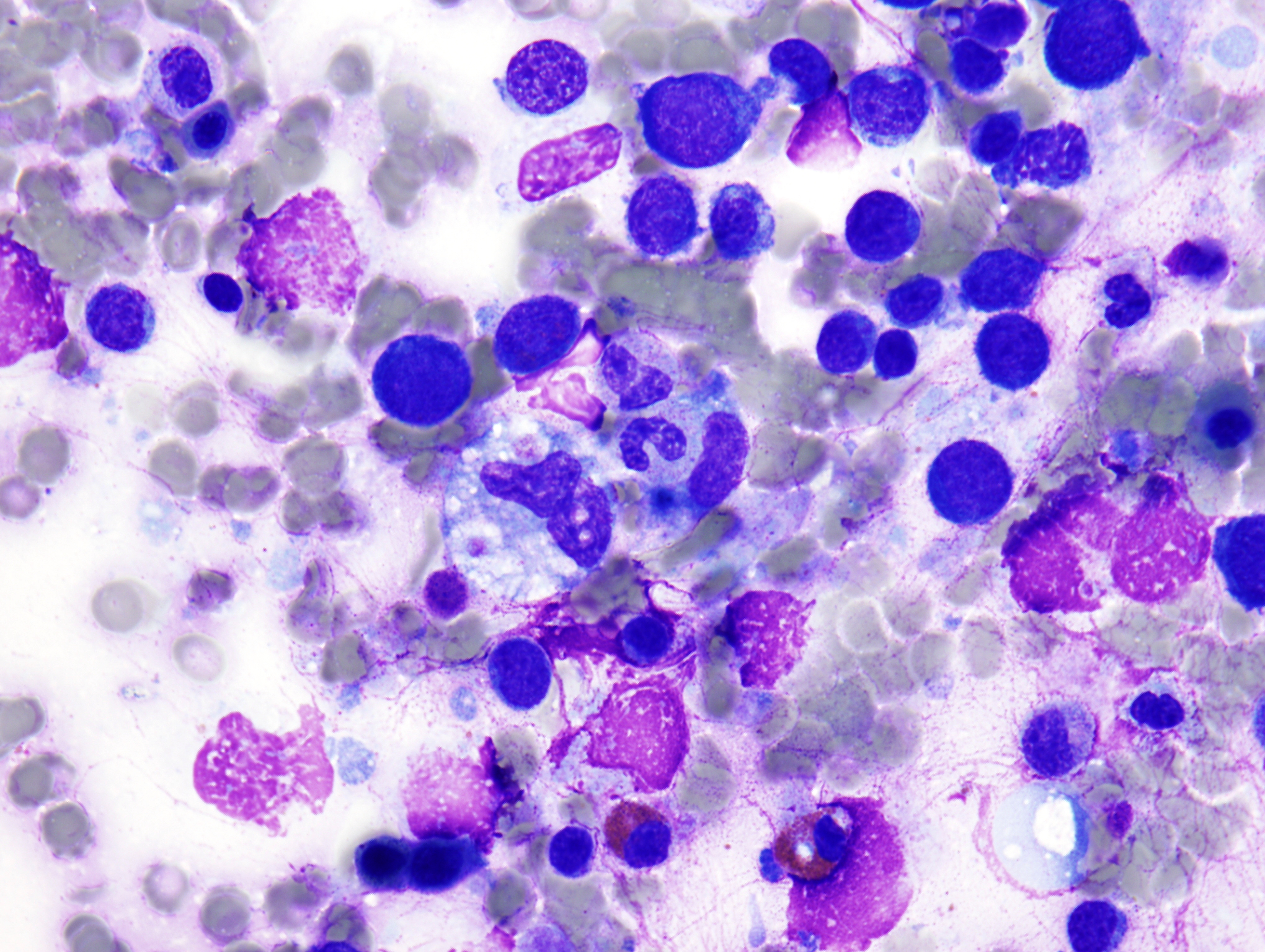

The peripheral smear demonstrated pancytopenia with normocytic, normochromic anemia, leukopenia, thrombocytopenia and no circulating blasts. Initially, the most striking features of the aspirate and core were the erythroid hyperplasia and erythroid dysplasia; a decrease in megakaryocytes was noted as well. Dysplastic features included megaloblastosis, abnormal nucleation, and multinuclearity in > 10% of the cells of erythroid lineage (Figures 1 and 2). The diagnosis of childhood MDS was considered; however, further inspection revealed hemophagocytosis of both erythrocytes and leukocytes throughout the specimen (Figures 3-5). These findings taken together with the clinical presentation and additional lab results – hypertriglyceridemia, elevated ferritin, decreased fibrinogen – ultimately led to a diagnosis of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis, secondary to recent EBV and CMV infections.

|

Figure 1 |

Figure 2 |

|

Figure 3 |

Figure 4 |

|

Figure 5 |

|

Discussion:

Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) is an aggressive, potentially life-threatening disease characterized by uncontrolled hyperinflammation. Cardinal symptoms include fever, hepatosplenomegaly, cytopenias and associated coagulopathy. Rash, lymphadenopathy and CNS symptoms may also be seen. Clearly the diagnosis may be easily missed, mistaken for an infectious process, malignancy or any number of other diseases with similar symptomatology. Biochemical markers include:

- Elevated triglyceride levels

- Elevated ferritin levels

- Elevated levels of the of soluble Il-2 receptor

- Elevated transaminases

- Elevated bilirubin levels

- Decreased fibrinogen

Despite the disease name, hemophagocytosis is found at presentation in only a handful of cases; instead, it tends to develop as the disease progresses. The initial bone marrow specimen may only reveal an increase in monocytes/histiocytes. Oftentimes, myelodysplastic syndrome may be suspected initially as marked dysplastic changes can be seen in the erythroid cell line. With regard to biochemical markers, LDH may be elevated, giving the impression of a hemolytic anemia; however, the reticulocyte count will not be elevated due to ineffective erythropoiesis.

HLH is categorized as either primary (Familial HLH - FHLH), an autosomal recessive disorder, or secondary (Acquired HLH). The clinical and biochemical manifestations are similar for both. FHLH is estimated to occur with a frequency of 1 in 50,000 births. Three genes have been associated with familial HLH: Perforin (PRF1); Munc13-4 (UNC13D); and Syntaxin11 (STX11). In addition, through linkage analysis, the 9q21.3-22 region has been found to be associated with HLH; no specific gene has been identified as yet. In the past it was believed that symptoms due to familial HLH always arose during infancy and early childhood. While 70% of cases present within the first year of life, it is becoming clear – with improvements in genetic testing – that the initial episode of HLH can occur anytime. In fact, there are cases documenting HLH from the prenatal period through the seventh decade.

Secondary HLH may be associated with:

- Infection:

- Viral:

- EBV, CMV, parvovirus, herpes simplex, VZV, HHV-8, measles, HIV

- Bacterial

- Brucella, Gram negatives and tuberculosis)

- Parasites (such as Leishmaniasis) and fungal infections

- Viral:

- Autoimmune disorders:

- SLE, RA, polyarteritis nodosa, MCTD, pulmonary sarcoidosis, systemic sclerosis and Sjogren syndrome.

- Malignancies:

- Leukemias and lymphomas (rare in children)

- Immune deficiencies:

- Chediak-Higashi syndrome (CHS)

- Griscelli syndrome (GS)

- X-linked lymphoproliferative syndrome (XLP)

It is important to note that distinctions between primary and secondary HLH are becoming blurred as more and more genetic links are being discovered. Furthermore, infection usually triggers HLH in an FHLH patient.

The clinical picture of HLH is due to an increased inflammatory response caused by hypersecretion of pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IFN-γ, TNF-α, soluble IL-2 receptor, IL-1b, IL-6, IL-8, IL-10 and IL-12. These mediators are secreted by an excessive proliferation of activated T lymphocytes and histiocytes which infiltrate all tissues. Cytokine production goes unchecked leading to inflammation, necrosis, organ dysfunction and ultimately, death. In spite of the excessive expansion of activated T-lymphocytes and histiocytes, patients with HLH have severe impairment of cells with cytotoxic function, namely natural killer (NK) cells and cytotoxic T-lymphoctes (CTL). NK cells and CTLs kill their targets via cytolytic granules containing perforin and granzyme. Upon contact between the effector cell and target cell an intracellular cytoskeletal scaffold rotates into the site where an immunological synapse forms between the two cells; cytotoxic granules are then carried along this scaffold to the synapse site. Upon contact between the effector cell and its target the cytotoxic granules degranulate, allowing perforin and granzyme to permeate the target cell membrane and deliver granzyme B into the target cell. Once internalized, granzyme B initiates apoptosis, destroying the target cell. Unfortunately, in HLH the cytotoxic capabilities of these cells (NK cells and CTLs) are disabled. As a result, activated T-lymphocytes and NK cells are incapable of eliminating infected cells and downregulating the antigen load. Because of this, the immune response – including the production of cytokines – continues in an attempt to rid the body of the unwanted antigen.

The diagnosis of HLH can be established if either:

- A molecular diagnosis consistent with HLH is made – Familial HLH:

- Perforin (PRF1), Munc13-4 (UNC13D), Syntaxin11 (STX11)

OR

- Five of eight diagnostic criteria for HLH are fulfilled (Familial and Acquired HLH):

- Clinical Criteria:

- Fever

- Splenomegaly

- Laboratory Criteria:

- Cytopenias (affecting at least 2 of 3 lineages):

- Hypertriglyceridemia and/or hypofibrinogenemia (fasting triglycerides >3.0 mmol/L, fibrinogen ≤1.5 g/L)

- Low or absent NK-cell activity (according to local laboratory reference).

- Ferritin > 500 microgram/L

- Soluble CD25 (i.e. soluble IL-2 receptor) > 2400 U/ml

- Histopathologic Criteria:

- Hemophagocytosis in bone marrow, spleen, CSF or lymph nodes; no evidence of malignancy

- Clinical Criteria:

Without treatment, HLH is usually rapidly fatal. In 1994, the Histiocyte Society developed a treatment protocol (HLH-94), predominantly for patients with FHLH; this protocol has since been slightly modified and now is known as HLH-2004. The HLH-94 protocol involves induction chemotherapy with dexamethasone, etoposide, cyclosporine (started at week 9), intrathecal methotrexate, plus pulses of dexamethasone and etoposide for up to 1 year. HLH-2004 is similar, except that cyclosporine is given on day 1 as opposed to waiting until week 9. The ultimate aim of these treatment protocols is to establish and maintain a stable clinical condition until the ultimate curative treatment, hematopoietic cell transplantation (HCT), can take place. HCT is appropriate for patients with familial, relapsing or severe and persistent HLH.

References:

- Filipovich, Alexandra. “Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH) and related disorders.” Hematology, 2009, pp. 127-131.

- Henter,Jan-Inge, M.D., PhD. “Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis (HLH).” Histiocytosis Association of America. http://www.histio.org/site/apps/nl/content2.asp?c=kiKTL4PQLvF&b=1850031&ct=2592057.

- Janka, Gritta and zur Stadt, Udo. “Familial and Acquired Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis.” Hematology, 2005. PP. 82-88.

- Jordan, Michael B., et al. “An animal model of hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis (HLH): CD8+ T cells and interferon gamma are esential for the disorder.” Blood, 2004. 104: 735-743.

- Lee, Je-Jung, et al. “Hemorrhagic Fever with Renal Syndrome Presenting with Hemophagocytic Lymphohistiocytosis.” CDC: Emerging Infectious Disease, Volume 8, Number 2, February 2002.

- McClain, Kenneth L., M.D., PhD. “Hemophagocytic lymphohistiocytosis.” Up To Date, 2009.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director