Case of the Month

February 2016 - Presented by Dr. Ananya Datta Mitra and Dr. Dorina Gui

Answer:

A. Metastatic melanoma to the small bowel

Histologic Description:

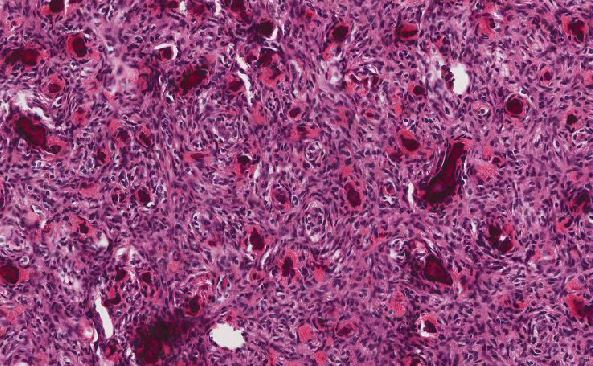

The tumor is involving the serosa, subserosa, muscularis propria and submucosa of the small bowel and colon. Microscopic examination showed nests of large cells with abundant eosinophilic and finely granular cytoplasm. (Figure C, 4X). The cells have prominent vesicular nuclei with large nucleoli. Prominent mitotic activity was also noted (Figure D, 20X).

Eleven of twenty lymph nodes are positive for metastatic melanoma (Figure E-F). The malignant cells were positive for S-100 (cytoplasmic and nuclear staining; Figure H), HMB-45 (cytoplasmic staining; Figure J), Sox-10 (nuclear staining; Figure G) and Melan-A (cytoplasmic staining; Figure J) and were negative for pankeratin AE1/AE3 (Figure K).

Discussion:

The immunohsitochemical stains strongly supported the diagnosis of metastatic melanoma.

Intestinal melanomas can be primary or metastases from cutaneous, ocular, or anal melanomas. Primary malignant melanomas of the small intestine are extremely rare (<2%) (1) and only a limited number of cases are described in literature (2, 3). Malignant melanoma accounts for 1–3% of all malignant disease in the gastrointestinal tract (GIT) (4) and cutaneous melanoma is one of the most common types of tumor to metastasize to the gastrointestinal tract (5). The small intestine is the most common site of melanoma metastases to the gastrointestinal tract (6). Distinction between a metastatic melanoma of the GIT from an unknown or a regressed primary lesion and a primary melanoma can be very difficult.

Primary melanoma of the small intestine

Primary melanoma of the small intestine is an extremely rare entity for which the cause is still a mystery. According to Mishima and colleagues (7), the origin of the disease might be from schwannian neuroblast cells associated with the autonomic innervation of the gut. Amar and co-workers (8) hypothesized that intestinal primary melanoma arise in melanoblastic cells of the neural crest, which migrate to the distal ileum through the omphalomesenteric canal. The amine-precursor uptake and decarboxylation (APUD) cell theory attributes ileum, to be the commonest site of primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine (9, 10).

Criteria to Diagnose Primary Melanoma

Diagnosis of primary intestinal melanoma is considered if histology shows a precursor lesion or melanosis in the intestinal mucosa (11). Histological features of metastatic intestinal melanoma that develop after spontaneous regression of primary cutaneous melanoma include lymphocytic infiltration of the dermis with melanophages, proliferation of atypical junctional melanocytes and melanocytic cells in the basal layer of surface epithelium, vascular proliferation, and reparative fibrosis (12). A clear distinction between primary intestinal melanoma and intestinal metastatic deposits can be difficult when considering histopathological features alone (13).

Criteria for the diagnosis of primary melanoma include absence of other primary site melanoma and no history of removal of melanoma or atypical melanocytic lesions from skin, retina, anal canal or occasionally at other locations like esophagus penis or vagina (2, 4).

To determine whether malignancy in the small bowel is a primary, Sacks et al. (14) established three diagnostic criteria : i) single lesion, ii) other organs free of primary lesions and absence of enlargement of draining lymph nodes and iii) survival time more than one year after the diagnosis (15).

In another study, Blecker et al. (6) recommended the following criteria for the diagnosis of primary melanoma of the small intestine: i) presence of a solitary mucosal lesion in the intestinal epithelium, ii) absence of melanoma or atypical melanocytic lesions of the skin and iii) presence of intramucosal melanocytic lesions in the overlying or adjacent intestinal epithelium.

Metastatic intestinal melanoma

Metastatic intestinal melanoma is very common in patients with a history of a cutaneous, anal, or ocular melanoma and among the affected individuals, the proportion with involvement of the small intestine ranges from 35% to 70% (5, 13, 16). Although approximately 60% of patients dying from melanoma have metastases to the GIT, only 1·5–4·4% of metastases are detected before death (16-19). Evidently, most patients with metastatic intestinal melanoma are clinically not diagnosed during their lifetime.

Superficial spreading melanoma is the most common type of cutaneous melanoma (70–80%) and the most prone to metastasize to the small intestine (20), although all cutaneous melanomas can do so. In contrast to primary intestinal melanoma, metastatic lesions are equally encountered in the ileum and jejunum (21). Bender and colleagues (21) defined four different types of metastatic melanoma of the small bowel: cavitary, infiltrating and polypoid, however, these types are not always distinct. Metastatic melanoma of the small bowel characteristically forms multiple polypoid masses (20) in the submucosal region and rarely presents as a solitary mass. Bender and colleagues (21) defined polyposis as the presence of more than ten polypoid lesions involving the jejunum and ileum. These polypoid lesions can be pigmented or amelanotic and ulceration in these lesions is very common (11, 21). Amelanotic lesions develop in almost half of all patients with metastatic intestinal melanoma and can coexist with melanotic tumors.

Most patients with metastatic intestinal melanoma are not diagnosed in early stages and come to attention only when complications occur or after death. Extraintestinal metastasis are detected in more than 50% of patients at the time of diagnosis (22). Although intestinal metastases classically develop 3–6 years after excision of the primary cutaneous melanoma, they are sometimes present at initial diagnosis or just 6 months after detection of primary cutaneous lesions (21, 23). Generally the symptom-free interval between surgical excision of cutaneous lesions and the diagnosis of small-bowel metastases lasts between 6 months and 90 months (22, 24).

Clinical presentation

Clinical presentation of small-intestine melanoma are abdominal pain (70%), intestinal obstruction, constipation, hematemesis, melena, anemia (20-50%), fatigue, weight loss, and presence of a palpable abdominal mass (10-20%) (11). Intestinal melanoma rarely presented as single or multiple polypoid lesions causing intestinal intussusception; bowel perforation (25). Substantial lymphadenopathy indicates spread to the mesenteric lymph nodes.

Diagnostic algorithm

Clinical examination with endoscopic and radiological imaging is essential for diagnosis of small-bowel melanoma. Diagnosis of intestinal melanoma is usually done by abdominal ultrasonography, conventional barium contrast studies, endoscopy, CT, or PET (26); however, the clinical detection rate is low (10–20%) (27). Routine radiographic screening for intestinal metastases is not recommended for patients with primary cutaneous melanoma or patients already diagnosed with metastatic disease not having gastrointestinal symptoms (20).

Treatment

Surgery is the treatment of choice both in patients with primary small-bowel melanoma and in those with intestinal metastatic melanoma (28). Wide surgical resection of the tumor with sufficient free margins proximally and distally from the lesion, together with mesentery to remove regional lymph nodes, is recommended in all patients in whom complete removal of the disease is feasible (4). Surgery is not a curative procedure for intestinal metastases and typically considered palliative for symptomatic lesions, however, complete resection of the tumor with free surgical margins might significantly improve prognosis with a 5-year survival rate of up to 40% and a disease-free period of up to 10 years (27). Yet, the median survival after complete tumor resection is 15 months (28).

No standard systemic therapies are available for patients with intestinal melanoma. Treatment of metastatic disease can include chemotherapy or immunotherapy (11). Both preoperative and postoperative chemotherapy regimens have been tried (29). In the past, immunotherapy with interleukin 2 was given alone or in combination with chemotherapy (30).

To summarize:

- Melanoma typically develops where melanocytes are found (skin, eyes, meninges, and anal region) and can also develop as a primary tumor in the small intestine.

- Primary tumors of the small bowel are rare, and most cases of small bowel melanoma are metastatic from cutaneous melanoma.

- The clinical picture of small-bowel melanoma is similar to the clinical presentation of other tumors involving the small intestine.

- Symptoms of intestinal melanoma present late in the progression of the disease, resulting in a poor prognosis.

- Although diagnosis is a challenge but can be made by abdominal ultrasound examination, barium contrast studies, endoscopy, CT, and PET.

- Surgical resection is a palliative procedure in patients with intestinal metastatic melanoma; however, in some patients, complete surgical resection of early diagnosed metastases in the intestine is associated with prolonged survival.

References

- Gill SS, Heuman DM, Mihas AA. Small intestinal neoplasms. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2001;33(4):267-82.

- Kruger S, Noack F, Blochle C, Feller AC. Primary malignant melanoma of the small bowel: a case report and review of the literature. Tumori. 2005;91(1):73-6.

- Mittal VK, Bodzin JH. Primary malignant tumors of the small bowel. Am J Surg. 1980;140(3):396-9.

- Atmatzidis KS, Pavlidis TE, Papaziogas BT, Papaziogas TB. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine: report of a case. Surg Today. 2002;32(9):831-3.

- Washington K, McDonagh D. Secondary tumors of the gastrointestinal tract: surgical pathologic findings and comparison with autopsy survey. Mod Pathol. 1995;8(4):427-33.

- Blecker D, Abraham S, Furth EE, Kochman ML. Melanoma in the gastrointestinal tract. Am J Gastroenterol. 1999;94(12):3427-33.

- Mishima Y. Melanocytic and nevocytic malignant melanomas. Cellular and subcellular differentiation. Cancer. 1967;20(5):632-49.

- Amar A, Jougon J, Edouard A, Laban P, Marry JP, Hillion G. [Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine]. Gastroenterol Clin Biol. 1992;16(4):365-7.

- Krausz MM, Ariel I, Behar AJ. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine and the APUD cell concept. J Surg Oncol. 1978;10(4):283-8.

- Tabaie HA, Citta RJ, Gallo L, Biondi RJ, Meoli FG, Silverman D. Primary malignant melanoma of the small intestine: report of a case and discussion of the APUD cell concept. J Am Osteopath Assoc. 1984;83(5):374-7.

- Liang KV, Sanderson SO, Nowakowski GS, Arora AS. Metastatic malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Mayo Clin Proc. 2006;81(4):511-6.

- Poggi SH, Madison JF, Hwu WJ, Bayar S, Salem RR. Colonic melanoma, primary or regressed primary. J Clin Gastroenterol. 2000;30(4):441-4.

- Crippa S, Bovo G, Romano F, Mussi C, Uggeri F. Melanoma metastatic to the gallbladder and small bowel: report of a case and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2004;14(5):427-30.

- Sachs DL, Lowe L, Chang AE, Carson E, Johnson TM. Do primary small intestinal melanomas exist? Report of a case. J Am Acad Dermatol. 1999;41(6):1042-4.

- Li G, Tang X, He J, Ren H. Intestinal obstruction due to primary intestinal melanoma in a patient with a history of rectal cancer resectioning: A case report. Mol Clin Oncol. 2014;2(2):233-6.

- Patel JK, Didolkar MS, Pickren JW, Moore RH. Metastatic pattern of malignant melanoma. A study of 216 autopsy cases. Am J Surg. 1978;135(6):807-10.

- Ihde JK, Coit DG. Melanoma metastatic to stomach, small bowel, or colon. Am J Surg. 1991;162(3):208-11.

- Dasgupta TK, Brasfield RD. Metastatic Melanoma of the Gastrointestinal Tract. Arch Surg. 1964;88:969-73.

- Reintgen DS, Thompson W, Garbutt J, Seigler HF. Radiologic, endoscopic, and surgical considerations of melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Surgery. 1984;95(6):635-9.

- Schuchter LM, Green R, Fraker D. Primary and metastatic diseases in malignant melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Curr Opin Oncol. 2000;12(2):181-5.

- Bender GN, Maglinte DD, McLarney JH, Rex D, Kelvin FM. Malignant melanoma: patterns of metastasis to the small bowel, reliability of imaging studies, and clinical relevance. Am J Gastroenterol. 2001;96(8):2392-400.

- Wade TP, Goodwin MN, Countryman DM, Johnson FE. Small bowel melanoma: extended survival with surgical management. Eur J Surg Oncol. 1995;21(1):90-1.

- Retsas S, Christofyllakis C. Melanoma involving the gastrointestinal tract. Anticancer Res. 2001;21(2B):1503-7.

- Caputy GG, Donohue JH, Goellner JR, Weaver AL. Metastatic melanoma of the gastrointestinal tract. Results of surgical management. Arch Surg. 1991;126(11):1353-8.

- Tarantino L, Nocera V, Perrotta M, Balsamo G, Schiano A, Orabona P, et al. Primary small-bowel melanoma: color Doppler ultrasonographic, computed tomographic, and radiologic findings with pathologic correlations. J Ultrasound Med. 2007;26(1):121-7.

- Kamel IR, Kruskal JB, Gramm HF. Imaging of abdominal manifestations of melanoma. Crit Rev Diagn Imaging. 1998;39(6):447-86.

- Albert JG, Gimm O, Stock K, Bilkenroth U, Marsch WC, Helmbold P. Small-bowel endoscopy is crucial for diagnosis of melanoma metastases to the small bowel: a case of metachronous small-bowel metastases and review of the literature. Melanoma Res. 2007;17(5):335-8.

- Agrawal S, Yao TJ, Coit DG. Surgery for melanoma metastatic to the gastrointestinal tract. Ann Surg Oncol. 1999;6(4):336-44.

- Lens MB, Eisen TG. Systemic chemotherapy in the treatment of malignant melanoma. Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2003;4(12):2205-11.

- Lens MB. The role of biological response modifiers in malignant melanoma. Expert Opin Biol Ther. 2003;3(8):1225-31.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director