Resident Program - Case of the Month

May 2019 - Presented by Alison Chan (Mentored by Chihong Zhou)

Discussion

The diagnosis in this case was ganglioneuroma, based on the morphology of the cell block and confirmed by immunohistochemistry. The specimen demonstrated dominantly Schwannian stroma composed of Schwann cells with wavy and tapered nuclei in a haphazard fashion and loose homogenous fibrous stroma. Rare large cells are also identified consistent with ganglion cells. The immunohistochemical staining supports the diagnosis: S100 positive, Neurofilament protein (NFP) positive, CD117 negative, and Smooth Muscle Actin (SMA) negative. The diagnosis was also later confirmed with the surgical mass excision. Of note, the cytology slides’ background consists of abundant sheets and groups of glandular epithelial cells with scattered goblet cells which are consistent with intestinal epithelium, secondary to the transduodenal procedure.

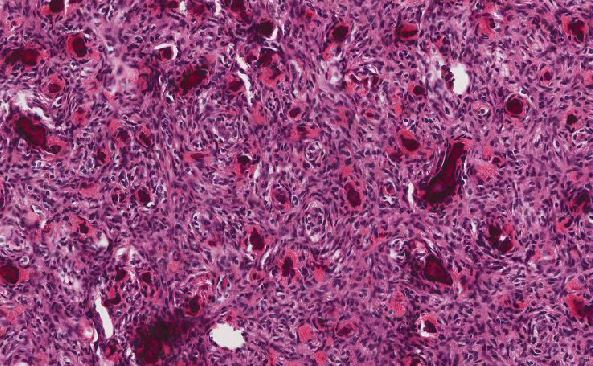

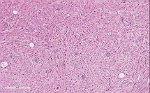

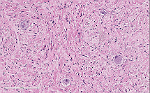

Below are images from the surgical resection specimen:

Click on images to enlarge.

Ganglioneuromas fall under the spectrum of neuroblastic tumors arising from primitive sympathetic ganglion cells. The undifferentiated and often clinically aggressive end of the spectrum is represented by neuroblastoma, which is the most common extracranial solid tumor of childhood. Ganglioneuromas represent the most differentiated end the spectrum of these neuroblastic tumors. The spectrum between the two ends is represented by ganglioneuroblastoma which may or may not have an aggressive clinical course. Ganglioneuromas are rare, fully differentiated benign tumors although they originated from neuroblasts.

Ganglioneuromas are most commonly located in the posterior mediastinum and retroperitoneum, but can also present in the adrenal glands and gastrointestinal tract. This lesion most commonly affects patients between the age of 10 to 30 years, with no gender predilection. Ganglioneuromas clinically present as a slow-growing, large solitary, painless mass and rarely is associated with catecholamine secretion that causes systemic symptoms, such as diarrhea and sweating. Though, it has been reported that up to 30% of patients may have elevated catecholamine levels without any clinical symptoms. Treatment consists of complete excision in which local recurrences are rare.

On all imaging modalities, the lesion will appear well circumscribed and homogenous. There may be extensive calcifications present. Adrenal ganglioneuromas are commonly identified as incidental findings, approximately 0.3%-2% of all adrenal incidentalomas. These tumors usually surround major blood vessels without compression or occlusion.

Grossly, ganglioneuromas are well-circumscribed, smooth, and encapsulated. These tumors have a rubbery texture that have a gray-white or yellow cut surface. It can have calcifications present, but hemorrhage and necrosis should be absent.

Microscopically, ganglioneuromas typically consists of abundant uniform spindled Schwann cells in a collagenous stroma that is intermixed with mature ganglion cells. These spindled cells usually have the classic wavy, elongated, and tapered nuclei that are arranged in fascicles or in haphazard patterns. The ganglion cells appear in clusters, nests, or singly and may vary in size and number. The surrounding stroma may demonstrate myxoid changes, cystic changes, fibrosis, calcifications or lymphoid aggregates. On immunohistochemistry, this neoplasm exhibit positivity with S100, neuron-specific enolase (NSE), synaptophysin, vimentin, and neurofilament protein (NFP).

The main differential diagnoses should include neurofibroma and schwannoma, both benign peripheral nerve sheath tumors. The presence of ganglion cells would not be a characteristic feature of either neurofibroma or schwannoma although Schwannian stroma might be seen in both of those lesions. Schwannomas will demonstrate compact hypercellular Antoni A areas and hypocellular Antoni B areas; and nuclear palisading around fibrillary process (Verocay bodies). Ganglioneuromas are also rich in unmyelinated axons, which is identifiable on immunostains for neurofilament protein (NFP). These structures are generally lacking in schwannoma. Ganglioneuromas should also be distinguished from their malignant counterparts, ganglioneuroblastomas and neuroblastomas, based on their lack of immature cells, neuropils and necrosis. The immature cells seen in the malignant counterparts vary from neuroblasts to a wide range of differentiation including some mature or nearly mature ganglion cells. In cases without the classic tapered and wavy nuclei, other spindle cell lesions should also be considered. These can be differentiated based on their specific immunohistochemical staining patterns.

| Diagnosis: | S100 | NFP | SMA | CD117 |

| Ganglioneuroma | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Schwannoma | Positive | Negative | Negative | Negative |

| Malignant Peripheral Nerve Sheath Tumor | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Neurofibroma | Positive | Positive | Negative | Negative |

| Leiomyoma | Negative | Negative | Positive | Negative |

| GIST | Negative | Negative | Negative | Positive |

Sources

Cibas ES, Ducatman BS. "Soft tissue. In: Cytology: Diagnostic Principles and Clinical Correlates". 4th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2014:488-491.

Decarolis B, Simon T, Krug B, et al. "Treatment and outcome of Ganglioneuroma and Ganglioneuroblastoma intermixed". BMC Cancer. 2016;16:542. Published 2016 Jul 27. doi:10.1186/s12885-016-2513-9.

Domanski HA. "Fine-needle aspiration of ganglioneuroma". Diagn Cytopathol. 2005 Jun;32(6):353-6. doi:10.1002/dc.20269.

Güler B, Özyılmaz F, Tokuç B, Can N, Taştekin E. "Histopathological Features of Gastrointestinal Stromal Tumors and the Contribution of DOG1 Expression to the Diagnosis". Balkan Med J. 2015;32(4):388–396. doi:10.5152/balkanmedj.2015.15912.

He WG, Yan Y, Tang W, Cai R, Ren G. "Clinical and biological features of neuroblastic tumors: A comparison of neuroblastoma and ganglioneuroblastoma". Oncotarget. 2017;8(23):37730–37739. doi:10.18632/oncotarget.17146.

"Immunoquery". Diagnosis Panel. Accessed March 22, 2019.

Jedynak, Andrzej. L Gill Naul, ed. "Imaging in Ganglioneuroma and Ganglioneuroblastoma". Medscape. WedbMD. Updated November 13, 2015. Accessed February 25, 2019.

Marino-Enriquez A, Hornick J. "3 – Spindle Cell Tumors of Adults". In: Practical Soft Tissue Pathology: a Diagnostic Approach: A Volume in the Pattern Recognition Series. 2nd edition. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2019:15-100.

Mylonas KS, Schizas D, "Economopoulos KP. Adrenal ganglioneuroma: What you need to know". World J Clin Cases. 2017;5(10):373-377.

Rodriguez FJ, Folpe AL, Giannini C, Perry A. "Pathology of peripheral nerve sheath tumors: diagnostic overview and update on selected diagnostic problems". Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123(3):295–319. doi:10.1007/s00401-012-0954-z

Shin, JH.; Lee, HK.; Khang, SK.; Kim, DW.; Jeong, AK.; Ahn, KJ.; Choi, CG.; Suh, DC. "Neuronal tumors of the central nervous system: radiologic findings and pathologic correlation". Radiographics. 22 (5): 1177–89.

Surbhi, Metgud R, Naik S, Patel S. "Spindle cell lesions: A review on immunohistochemical markers". Journal of Cancer Research and Therapeutics. 2017;13(3):412-418. doi: 10.4103/0973-1482.176178.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director