Resident Program - Case of the Month

December 2019 - Presented by Dr. Alison Chan (Mentored by Dr. Regina Gandour-Edwards)

Discussion:

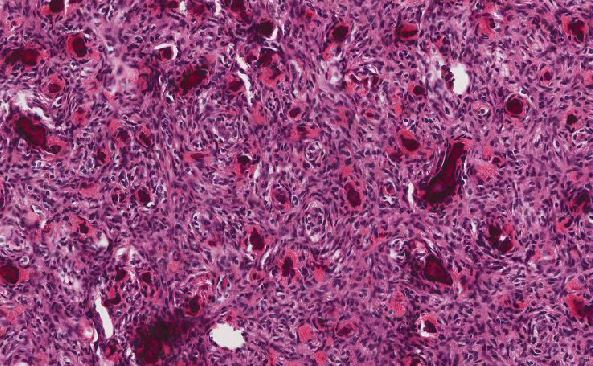

The diagnosis in this case was small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, based on the morphology and confirmed by immunohistochemistry. This tumor has the classic nested pattern of small round tumor cells in an organoid architecture. The cells exhibit a high nucleus to cytoplasmic ratio with finely granular and evenly dispersed “salt and pepper” nuclear chromatin and inconspicuous nucleoli. The cells are positive for CD56 and synaptophysin, which support the diagnosis.

Small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma is a rare tumor of the bladder, accounting for less than 1% of bladder cancer cases. It is categorized as a neuroendocrine tumor (NET), which includes the large-cell carcinoma of the bladder and carcinoid tumors. Although small cell carcinoma is rare, it is the most common NET of the bladder and is very aggressive with a poor prognosis. This entity affects predominantly Caucasians and usually males more than females at a 3:1 ratio. Individuals commonly present at 60-70 years of age range and are usually diagnosed at advanced stages with frequent metastases.

There are no known specific causes to the development of small cell carcinoma, but smoking has been thought to be a risk factor. There are several theories on the pathogenesis of the small cell carcinoma of the bladder. One theory is where small cell carcinoma is of urothelial origin where it arises through metaplastic changes. This theory arises due to the frequent association of small cell carcinoma with the different variants of urothelial carcinomas. It could explain how smoking is a risk factor for both types of cancers. A second theory is the tumor arises from a urothelial stem cell. A third belief is that the scattered neuroendocrine cells within the bladder undergo a malignant transformation.

An individual with small cell carcinoma of the bladder usually presents with painless gross hematuria. This is the most common symptom and can be associated with dysuria, obstructive symptoms, weight loss, abdominal pain, and recurrent urinary tract infections. However, many of these symptoms are nonspecific and can be seen in other genitourinary tract diseases. Rarely, they can present with paraneoplastic syndromes which include hypercalcemia, hyperphosphatemia, and ectopic adrenocorticotropin hormone (ACTH) secretion. Commonly, urologists will perform a cystoscopy to visualize the size and location of the tumor. A transurethral resection of the bladder tumor (TURBT) can be performed to acquire tissue for pathologic diagnosis or for therapeutic removal of the tumor. Histologic examination of biopsied tissue allows for an accurate diagnosis. Exfoliative urine cytology may or may not show the tumor cells.

On gross examination, the tumor may be large, solid, single or multiple, nodular or polypoid, and is located most commonly in the lateral walls and the dome. The tumor may or may not show ulceration of the urothelial surface. This tumor can also be grossly seen to be infiltrating into the rest of the bladder. Upon gross exam of the tumor, one cannot distinguish between a small cell carcinoma from a urothelial carcinoma, especially when the two entities may co-exist. Metastases frequently involve the regional lymph nodes. However, it can spread to distant areas such as the bone, liver, and lung.

Histologically, the small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma has a similar morphology as other neuroendocrine tumors. The tumor will have nests, sheets, or trabeculae of small round to oval cells with a high nucleus to cytoplasm ratio. The cells are loosely attached to each other, have evenly dispersed granular chromatin in a “salt and pepper” appearance. There will be scant cytoplasm with inconspicuous nucleoli. The Azzopardi phenomenon can be present, where DNA from crushed cells are present within necrotic venules. This finding was not present in this case. The mitotic count will be high with more than 20 mitoses per high power field.

Immunohistochemical stains can be used to support the diagnosis. The stains that are commonly positive are neuron-specific enolase (NSE), chromogranin-A, synaptophysin, CD57, and CD56. Small cell carcinoma can be positive for epithelial markers, such as cytokeratin 7 (CK7), epithelial membrane antigen (EMA), and CAM 5.2. It should be noted that cytokeratin CAM 5.2 stains positively in both urothelial carcinoma as well as small cell carcinoma, but urothelial carcinoma stains along the membrane while small cell carcinoma has a dot-like perinuclear pattern.

The differential for a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma includes lymphoma, high-grade urothelial carcinoma, large-cell carcinoma of the bladder, and metastases from another neuroendocrine tumor. Lymphoma can be seen arising in the urinary tract and accounting for less than 5% of all extranodal lymphomas and less than 1% of all primary neoplasms of the urinary tract. Patients will clinically present similarly with one or more lesions present with possible erythema or ulceration of the urothelium seen on cystoscopy. Immunohistochemical stains can be used to distinguish it from a small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma, where lymphoma is positive for leukocyte common antigen (LCA) and negative for neuroendocrine and cytokeratin markers. Large-cell carcinoma of the bladder has a different cytologic appearance with large polygonal cells, low nuclear to cytoplasmic ratio, frequent nucleoli, coarse chromatin, and a high mitotic rate. The immunohistochemical staining pattern will be like the small cell neuroendocrine carcinoma. A high-grade urothelial carcinoma may mimic a small cell carcinoma if it has scant cytoplasm and can be found to coexist in the same tumor. However, the cytologic features show marked pleomorphism with coarse nuclear chromatin and prominent nucleoli. It should stain negatively for the neuroendocrine specific stains. Metastases from another organ site, such as the lung, should be ruled out using clinicopathologic correlation because immunohistochemistry may not be helpful. There are cases of small cell carcinoma of the bladder that stain positively with TTF-1, thus the stain cannot rule out a metastatic lung small cell carcinoma versus a primary bladder small cell carcinoma.

Sources:

Çamtosun A, Çelik H, Altıntaş R, Akpolat N. Primary small cell carcinoma in urinary bladder: a rare case. Case Reports in Urology. 2015;2015. https://doi.org/10.1155/2015/789806.

Cattrini C, Zanardi E, Rubagotti A, Boccardo F. Small cell neuroendocrine bladder cancer: an organ-specific perspective – beyond the abstract. Urotoday. 2019, June 24. https://www.urotoday.com/recent-abstracts/urologic-oncology/bladder-cancer/113239-small-cell-neuroendocrine-bladder-cancer-an-organ-specific-perspective.html. Accessed 10/30/19.

Ghervan L, Zahari A, Ene B, Elec FI. Small-cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: where do we stand? Clujul Medical. 2017;90(1):13-17. doi: 10.15386/cjmed-673

Holger Moch, Peter A. Humphrey, Thomas M. Ulbright, Victor E. Reuter (Eds): WHO Classification of Tumours of the Urinary System and Male Genital Organs (4th edition). IARC: Lyon 2016.

Ismaili N. A rare bladder cancer--small cell carcinoma: review and update. Orphanet J Rare Dis. 2011;6:75. Published 2011 Nov 13. doi:10.1186/1750-1172-6-75

Zhao X, Flynn EA. Small cell carcinoma of the urinary bladder: a rare, aggressive neuroendocrine malignancy. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine. November 2012;136(11):1451-1459.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director