Resident Program - Case of the Month

Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor (PMT) is a rare neoplasm most known for its association with tumor-induced osteomalacia (osteogeneic osteomalacia). PMTs occur over a wide age range but arise most commonly in middle-aged adults with an equal predilection for males and females. They most often occur in the extremities but can arise in any bone or soft tissue site. PMTs secrete fibroblast growth factor-23 (FGF-23), a protein which inhibits renal phosphate reabsorption in the proximal tubules. This results in phosphaturia, bone demineralization, and eventually osteomalacia. Clinically, most patients present with osteomalacia-related symptoms (e.g. pain due to widespread fractures). Rarely, PMTs can present without clinical evidence of phosphaturia and tumor induced osteomalacia.

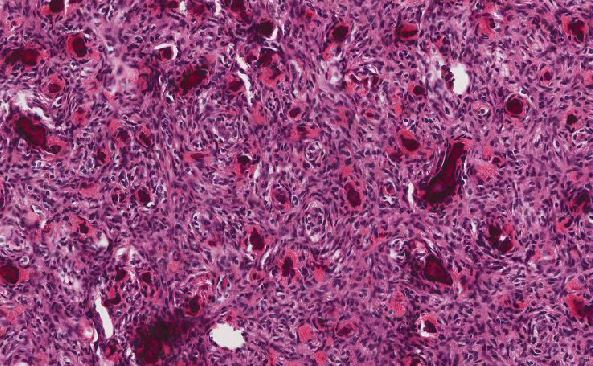

Histologically, these tumors are typically composed of non-descript spindle to stellate-shaped cells. There is often a characteristic chondromyxoid matrix with distinctive “grungy” or granular material. Well-developed capillary vascular networks can be present. Hemorrhage, ossification, and osteoclast-like multinucleate giant cells may also be present. Decalcification can obscure the distinctive calcification and make recognizing the PMT more difficult.

Most PMTs are histologically and clinically benign. Malignant PMTs are very rare but typically occur in the setting of repeated recurrences. Malignant PMTs can be recognized by typical histologic features of malignancy (e.g. hypercellularity, cytologic atypia, and frequent mitoses). Local recurrence is common even in benign PMTs. Complete surgical excision is the recommended treatment as this removes the FGF-23 source. The tumor-induced osteomalacia usually resolves following excision.

Due to their rarity, PMTs often go unrecognized or are misdiagnosed. Awareness of this entity is key for both clinicians and surgical pathologists to make the appropriate diagnosis. Initial clinical recognition of tumor-induced osteomalacia and determination of elevated serum FGF-23 levels should provide a high index of suspicion for a PMT. A thorough survey including imaging is often necessary to locate the site of the PMT. Localizing and accurately diagnosing the tumor are critical as surgical excision is the definitive treatment. Both clinicians and pathologists should keep in mind that, as in this patient’s case, more than one lesion may be identified clinically and that a non-PMT lesion may be biopsied first.

This patient’s sternum was subsequently resected and showed similar histologic features to the biopsy. One month after the resection, follow-up testing showed that the patient’s serum FGF-23 level had normalized.

References:

- Ghorbani-Aghbolaghi A, Darrow MA, Wang T. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor (PMT): exceptionally rare disease, yet crucial not to miss. Autops Case Rep. 2017 Sep 30;7(3):32-37.

- Folpe et al. Most Osteomalacia-associated Mesenchymal Tumors Are a Single Histopathologic Entity: An Analysis of 32 Cases and a Comprehensive Review of the Literature. Am J Surg Pathol. 2004 Jan; 28(1):1-30.

- Agaimy A, Michal M, Chiosea S, Petersson F, Hadrasky L, Kristiansen G, Horsch RE, Schrmolders J, Hartmann A, Haller F, Michal M. Phosphaturic Mesenchymal Tumors: Clinicopathologic, Immunohistochemical and Molecular Analysis of 22 Cases Expanding their Morphologic and Immunophenotypic Spectrum. Am J Surg Pathol. 2017 Oct; 41(10):1371-1380.

- Sent-Doux KN, Mackinnon C, Lee JC, Folpe AL, Habeeb O. Phosphaturic mesenchymal tumor without osteomalacia: additional confirmation of the “nonphosphaturic” variant, with emphasis on the roles of FGF23 chromogenic in situ hybridization and FN1-FGFR1 fluorsescence in situ hybridization. Hum Pathol. 2018 Oct;80:94-98.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director