Resident Program - Case of the Month

May 2022 – Presented by Dr. Melissa Ha (Mentored by Dr. Han Sung Lee)

Discussion

Paragangliomas are rare catecholamine-secreting neuroendocrine neoplasms composed of chromaffin cells and most commonly proliferate from paraganglia (sympathetic or parasympathetic) or the adrenal medulla (known as pheochromocytomas). Thus, extra-adrenal paragangliomas are more commonly found in the head, neck, upper thorax, and along the prevertebral and paravertebral sympathetic chain, making the appendix an unusual site for a paraganglioma. However, they can arise aberrantly in any area of the body that contain embryonic neural crest cells. Distinct signs and symptoms on presentation can be due to catecholamine effects, but they may also be asymptomatic and discovered incidentally.

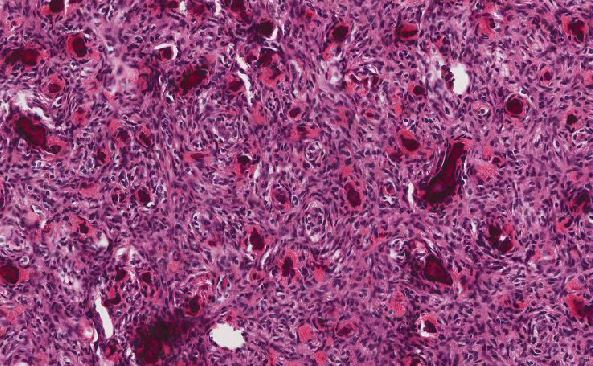

When diagnosing such tumors, the most salient feature histologically is the Zellballen pattern of growth in which neoplastic cells proliferate in distinct clusters and nests. Cells will stain chromogranin positive, synaptophysin positive, GATA3 positive, and pankeratin negative. S100 highlights the “sustentacular cells” rimming the zellballen. Important differential diagnoses to consider include neuroendocrine “carcinoid” tumors (NET) which can look histologically similar but will stain pankeratin positive and infrequently stain S100 positive. SATB2 and CDX2 can help distinguish NET of rectal/appendiceal or small intestine origin, respectively. Parathyroid tumors will also stain positive for neuroendocrine markers, and GATA3, but will stain negative for S100 and positive for pankeratin instead.

All paragangliomas have metastatic potential, but multifocal primary tumors can frequently occur, so definitive metastasis is diagnosed when such tumors are found in sites lacking chromaffin tissue like bone, brain, and lymph nodes. However, molecular markers can help to inform clinical prognosis. Specifically, mutations in the mitochondrial enzyme succinate dehydrogenase B subunit (SDHB) carry the strongest genetic association with malignancy and metastasis, thus warranting a check for the SDH status of the tumor. Although not definitive nor universally accepted, risk stratification systems can also be used to help determine malignant potential. Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS), adapted for paragangliomas, is one such system. Each microscopic feature listed in the table below is assigned a score. A combined weighted score of 4 or greater predicts biologically aggressive behavior.

| PASS microscopic features | Score |

| Vascular invasion | 1 |

| Capsular invasion | 1 |

| Periadipose tissue invasion | 2 |

| Large nests or diffuse growth | 2 |

| Focal or confluent necrosis | 2 |

| High cellularity | 2 |

| Tumor cell spindling | 2 |

| Cellular monotony | 2 |

| Mitotic figures >3/10 HPF | 2 |

| Atypical mitotic figures | 2 |

| Profound nuclear pleomorphism | 1 |

| Hyperchromasia | 1 |

(Thompson LDR, 2002)

In general, complete surgical excision is the mainstay treatment and is often curative. Preoperative management with catecholamine blockers may be necessary for hormone secretors. Of note, pheochromocytoms and paragangliomas can be sporadic, but almost one-third have familial etiology and are associated with various syndromes including von Hippel-Lindau (VHL), multiple endocrine neoplasia (MEN1 and MEN2), neurofibromatosis type 1 (NF1), and Hereditary leiomyomatosis and renal cell carcinoma (HLRCC).

References

- Delfin L, Asa SL. Paraganglioma. PathologyOutlines.com website. Accessed April 21st, 2022.

- Ikram, A., & Rehman, A. (2021). Paraganglioma. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing.

- Thompson L. D. (2002). Pheochromocytoma of the Adrenal gland Scaled Score (PASS) to separate benign from malignant neoplasms: a clinicopathologic and immunophenotypic study of 100 cases. The American journal of surgical pathology, 26(5), 551–566.

- Kantorovich V, King KS, Pacak K. SDH-related pheochromocytoma and paraganglioma. Best Pract Res Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2010;24(3):415-424. doi:10.1016/j.beem.2010.04.001

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director