Resident Program - Case of the Month

September 2022 – Presented by Dr. Heather Greene (Mentored by Dr. Anna Romanelli and Ellen Papathakis, CLS)

Discussion

The organism isolated in this case, which was found in the patient’s blood and cerebrospinal fluid, was Haemophilus influenzae. H. influenzae is grouped into two basic varieties, encapsulated (“typeable”) or unencapsulated (“nontypeable”). The capsule may contain one of six antigens (a-f), with antigen type b being the most clinically relevant. The antiphagocytic polysaccharide capsule is the primary virulence factor of H. influenzae. Unencapsulated H. influenzae is a member of the normal upper respiratory flora, colonizing at least 50-80% of people.1 As respiratory organisms, H. influenzae infections begin in the respiratory tract, sinuses, or middle ear. Typically, only encapsulated H. influenzae can invade into the bloodstream to cause sepsis or meningitis, while all strains can cause otitis media or acute sinusitis.1 The rate of carriage of the typeable varieties is low, 1-2%, and the carriage rate of type b is <1% since the development of the vaccine.1

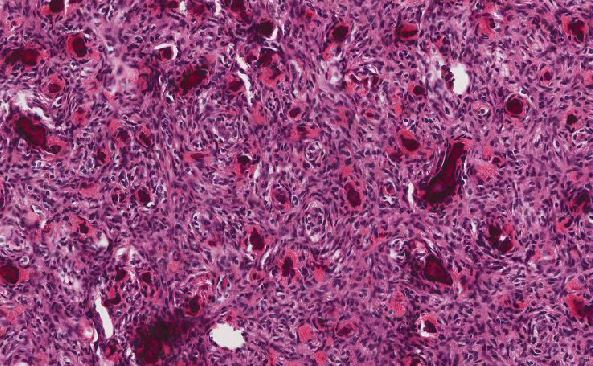

H. influenzae are small, pleomorphic, gram-negative bacteria which vary in morphology according to their growth medium and length of incubation.1 While they often take on a coccobacillary form, the H. influenzae seen in this case took on a pleomorphic, ballooned appearance. While typeable H. influenzae isolates (e.g., type b) often show an obvious capsule, this isolate did not. A sample of the isolate from this case was sent to an outside laboratory for capsular antigen typing, with the results currently pending.

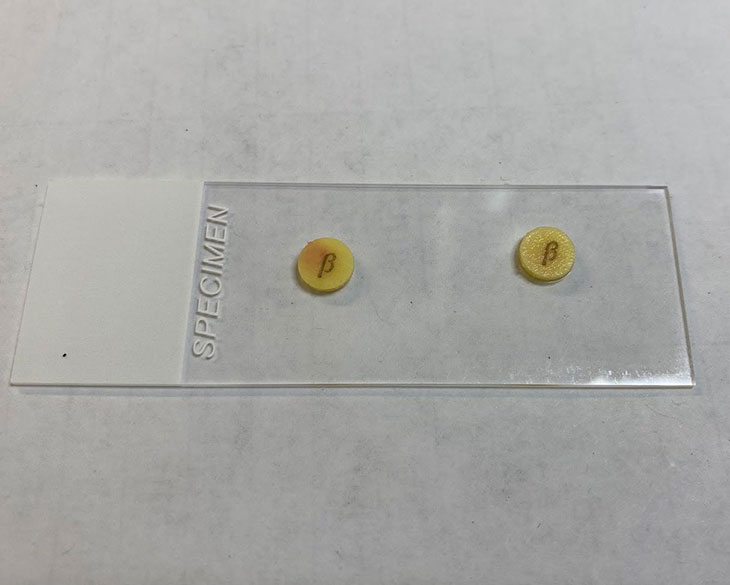

In our case, the organism was identified by the Biofire FilmArray identification instrument for both the blood and CSF specimens, then MALDI-TOF was utilized to confirm the identity of the pure colonies growing on the chocolate agar. Aerobic growth of H. influenzae requires factors X and V, which are not available to the organism on standard sheep blood agar plates. However, these are released during the heating process when chocolate plates are produced, hence its ability to grow on chocolate agar only. On the other hand, H. influenzae is able to grow on sheep blood agar only with the supplementation of the X and V factors. In this case, the satellite test is performed, where an isolate of Staphylococcus aureus is streaked down the middle of the sheep blood agar plate already inoculated with H. influenzae. S. aureus facilitates the release of factors X and V from the blood, enabling the H. influenzae to grow around the streak line, also referred to as satelliting. Since 25% of Haemophilus influenzae isolates produce a beta-lactamase, beta-lactamase testing was performed on the isolate to guide treatment (see image). Although this isolate did not produce a beta-lactamase, the patient was continued on ceftriaxone since third-generation cephalosporins are the first-line treatment for H. influenzae meningitis.2

Image: Beta-Lactamase Test (positive control on left and patient’s isolate on right)

In this case, the 6-month-old otherwise healthy baby was not vaccinated against HiB, which was a significant risk factor for his infection. Prior to the Haemophilus influenzae type b (Hib) vaccine, Hib was the leading cause of meningitis in children under 5 years of age.3 Haemophilus influenzae type b was also the major cause of epiglottitis, and was also implicated in many cases of pneumonia, sepsis, cellulitis, and arthritis.4 It is recommended that all infants receive the Hib vaccine series starting at around 8 weeks of age and receive 3-4 Hib vaccines in total, depending on which FDA-recommended vaccine schedule is chosen.

While infection with H. influenzae type b does not pose a significant risk of transmission to adults, nonimmune siblings and nonimmune close contacts under 4 years old are at risk.1 In this case, the patient had two unvaccinated siblings, one of whom had a cough at the time of his diagnosis. She was admitted for observation and prophylactic antibiotics. She did not have any positive blood cultures, and her symptoms were determined to be due to an unrelated viral upper respiratory infection.

Invasive Haemophilus influenzae infections are reportable conditions in all fifty states. Through this protocol, the CDC tracks the effectiveness of Hib vaccines and monitors for emerging strains. While invasive infections due to H. influenzae type b remain low, rates of invasive infections due to other non-b types and nontypeable H. influenzae are increasing.5

References

- Haemophilus, Bordetella, Brucella, and Francisella. In: Riedel S, Hobden JA, Miller S, Morse SA, Mietzner TA, Detrick B, Mitchell TG, Sakanari JA, Hotez P, Mejia R. eds. Jawetz, Melnick, & Adelberg's Medical Microbiology, 28e. McGraw Hill; 2019. Accessed August 28, 2022.

- Joseph W. St. Geme, Katherine A. Rempe, 172 - Haemophilus influenzae, Editor(s): Sarah S. Long, Charles G. Prober, Marc Fischer, Principles and Practice of Pediatric Infectious Diseases (Fifth Edition), Elsevier, 2018, Pages 926-931.e3, ISBN 9780323401814

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Haemophilus Influenzae Type b (Hib) VIS. Accessed August 28, 2022.

- Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. A Look at Each Vaccine: Haemophilus Influenzae Type B (Hib) Vaccine. Accessed August 28, 2022.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Haemophilus Influenzae Disease (including Hib): Surveillance. Accessed August 28, 2022.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director