17-year-old Roseville girl nearly dies of walking pneumonia

Teen reunites with UC Davis Health team that saved her life

It was a happy homecoming for 17-year-old Callie McCune, who returned to UC Davis Children’s Hospital in October, two months after her hospital stay.

She was walking and talking, beaming with excitement to thank the team who saved her life.

“Her recovery has been so inspiring,” said UC Davis pediatric critical care physician Kate Phelps. “It was wonderful to see Callie again doing so well.”

It was a 180-degree transformation from her time in the Pediatric Intensive Care Unit (PICU), fighting for her life.

A cold that led to hospitalization

Callie had a cold in August, but her cough lingered and wouldn’t quit.

Callie didn’t have a history of breathing problems, but when her coughing led to vomiting, her mother took her to the nearest emergency room. She learned then that Callie had mycoplasma pneumonia, a bacterial pneumonia that is also called “walking pneumonia.”

She was admitted to her local hospital. Her oxygen level was at about 93% and she was given a face mask that fit over her nose and mouth, allowing her to breathe air from a ventilator.

Within the next 24 hours, she went through four ventilators with little improvement.

“They tried everything. She was declining rapidly,” remembered Cara Cosentino, Callie’s mother.

Fluid was filling Callie’s left lung. She was diagnosed with acute respiratory distress syndrome, a life-threatening lung injury that allows fluid to leak into the lungs.

She was intubated (a breathing tube was placed into her windpipe and the breathing tube was connected to a ventilator) and transferred to UC Davis Children’s Hospital to get the advanced level of care that she needed.

Less than 50% chance of survival

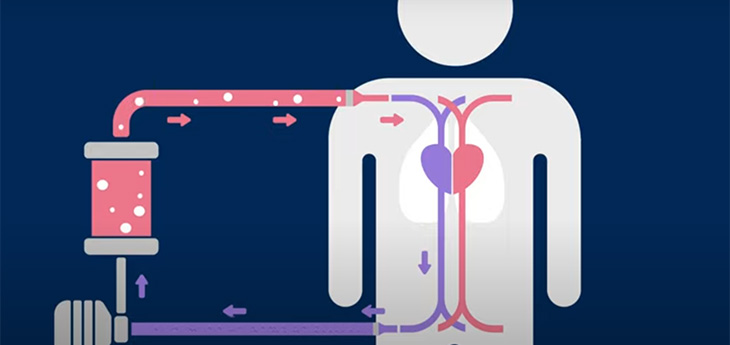

Once Callie was admitted to the PICU at UC Davis Children’s Hospital, her doctors recommended Extracorporeal Membrane Oxygenation (ECMO), a heart-lung bypass machine to give Callie’s lungs a chance to heal. UC Davis Children’s Hospital’s ECMO program recently received the Extracorporeal Life Support Organization’s Gold Award for Excellence in Life Support.

“We signed the paperwork for ECMO and they gave us the chance for our whole family to come in and say goodbye to her. We had no time to digest what was happening. She was deteriorating so fast,” Cosentino said.

Doctors told Cosentino that she had less than a 50% chance of survival.

Callie was placed on the ECMO machine by midnight. She had two people at her bedside at all times. A specially trained ECMO nurse was there to manage the ECMO machine. A bedside nurse was also there to take care of Callie’s needs. Callie was in a special bed that tilted so that her body was nearly vertical. This took pressure off her lungs.

“Those were some challenging times. We were praying for miracles every day and the outlook wasn’t very good,” Cosentino said.

A new diagnosis

While Callie was on ECMO, another complication emerged. Callie was getting her blood drawn daily and her blood was clotting before it even got to the lab.

She was diagnosed with cold agglutinin disease, a rare autoimmune disease in which the body’s immune system attacks red blood cells. It most commonly affects seniors over the age of 65, but Callie had it.

“There was a one-in-a-million chance of her getting that. Almost every day at least one doctor told me that they had never seen this before in someone Callie’s age,” Cosentino said.

Despite these setbacks, Cosentino said that she never lost hope that her daughter would recover. She said they would play music every night for Callie — Taylor Swift was one of her favorites — and Cosentino stayed by her daughter’s bedside.

After 10 days on ECMO, the team took Callie off of the ECMO machine — and her lungs had to start working once again on their own.

“Some people who go through ECMO don’t come out of it or they remain catatonic. But miracles do happen and Callie was our true miracle,” Cosentino said.

Just as they had hoped, Callie was able to breathe on her own. Then slowly, more milestones served as beacons of hope.

“I remember the one day I was able to give her a hug. That was big. I knew we had a chance,” Cosentino said. “Once she was off of ECMO, she was hellbent on getting home and she worked toward that goal.”

Callie started physical and occupational therapy every day once she was off of ECMO. She began to regain her mobility once more. She communicated through sign language (something she learned by taking ASL in high school) and by writing on a dry erase board since she remained on a ventilator through the end of her hospital stay.

Callie was discharged from UC Davis Children’s Hospital on Sept. 18 and was transferred back to her local hospital for care.

So often, our patients leave the ICU and we do not get to see them again. Seeing her walk through those doors smiling, talking and healthy is the most rewarding feeling.”—Laura Kenny

Returning to normal life

Callie is now a senior in high school and continues to get better each day. She has graduated from occupational therapy and continues with physical therapy twice a month. She sees her pediatrician twice a week, where they monitor her oxygen levels, which have improved significantly.

Cosentino calls Callie’s recovery a miracle. She credits a lot of prayers and her daughter’s care team, who got her through the toughest days.

“The doctors, nurses, the whole team were amazing. We just can’t thank them enough. They saved my baby,” Cosentino said.

Cosentino was grateful for the opportunity to bring her daughter back to the PICU to show the team how far she has come.

“So often, our patients leave the ICU and we do not get to see them again,” said Laura Kenny, assistant nurse manager of pediatric critical care and the ECMO/ECLS coordinator. “Seeing her walk through those doors smiling, talking and healthy is the most rewarding feeling.”