Toxic stress in childhood can lead to chronic health conditions. Here are 4 ways to protect your kids.

In California, 1 in 3 children is at risk for toxic stress and nearly 2 million children are affected by adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). When a child encounters ACEs, which can include abuse, neglect or household challenges like substance abuse at home or the incarceration of a parent, it can trigger toxic stress. Prolonged exposure to toxic stress can lead to ACE-related health conditions including chronic lung disease, heart disease and mental health conditions.

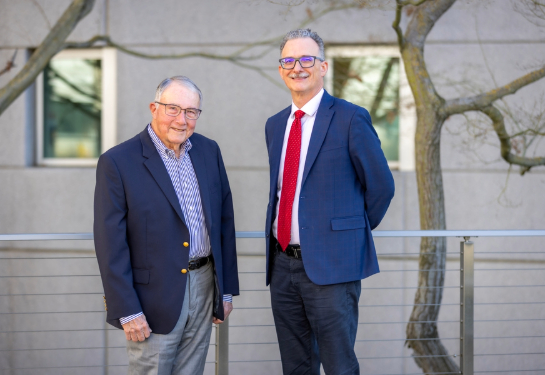

In the latest Kids Considered two-part podcast episode about toxic stress, UC Davis pediatrician Lena van der List and UC Davis chief of pediatric infectious diseases Dean Blumberg focus on this subject. They talk with pediatrician and author Nadine Burke Harris, who is the former First Surgeon General of California and former First 5 California chair; and Jackie Thu-Huong Wong, executive director of First 5 California.

In this Q&A, Burke Harris and Wong share resources and discuss what parents can do to protect their children from the effects of toxic stress.

Tell us about the original ACEs study, conducted by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and Kaiser Permanente, in the mid-1990s.

Burke Harris: This research helped doctors and clinicians understand that when we experience stress or trauma, it can affect our health.

The study found that:

- 2/3 of children in the study experienced one or more of these ACEs.

- 8% (one in 8) experienced four or more ACEs.

The other striking thing was that the more of these ACEs a person has, the greater the risk to their health. For someone who experienced four or more ACEs:

- Their risk for heart disease was double.

- For depression, the risk was 4.5 times.

- For chronic lung disease, the risk was more than double.

Understanding that gives us the opportunity to do something about it. That’s the piece that was exciting to me.

Can you describe how experiencing toxic stress can actually change a person’s physiology over time?

Burke Harris: Toxic stress can trigger stress hormones like cortisol in our brain. When we experience something scary, that activates our brain’s alarm system. These makes our heartbeat faster. It affects our adrenaline, increases our blood pressure. Prolonged activation of the stress response can change the way a child’s immune system functions.

How can parents and providers recognize signs of toxic stress? Are there specific behaviors they should look out for?

Burke Harris: In kids, it can mean headaches, tummy aches, frequent infections and asthma triggers. It can lead to difficulty with attention and learning, challenges with mood, depression, anxiety or suicidal ideation. It can affect a child’s growth and their height.

What is the appropriate treatment for ACEs?

Wong: The treatment is to create safe, stable, nurturing relationships and environments. The four ways to build resilient kids are:

- Be calm. Calmness creates a peaceful environment that helps children manage their emotions.

- Be steady. Being consistent helps make the world more predictable for children.

- Be there. Singing, reading and playing with kids can help their brains grow.

- Be nurturing. Showing love and affection builds a safe and secure connection.

According to data, more than 60% of California adults have experienced at least one ACE and 16.3% have experienced four or more ACEs. Many of these people will go on to have a child. How can parents work to ensure that their own exposures to toxic stress are not passed on to their children?

Wong: To stop the intergenerational transfer of stress, educating parents and raising awareness are key. And letting families know that they are not alone. That’s the basis of the Stronger Starts campaign. The first step is in knowing what is toxic stress and what are ACEs.

Many health care providers have incorporated screening for ACEs in their pediatric wellness visits. We use the PEARLS (pediatric ACEs and life events screener). How should health care providers explain this screening to families in the clinic?

Burke Harris: I’ve been screening for ACEs since 2008. I’ve had a lot of conversations with parents and helping families understand why we are doing this screening.

New science is telling us that exposures to these experiences can lead to increased risk of different health conditions and learning difficulties. We screen everybody now. That’s important and can be reassuring to families. This is a public health issue. The research shows the earlier we intervene, the better outcomes are. The goal of the screening is to identify and provide supports and resources to reduce your child’s health risk.

Are there effective strategies or interventions parents and providers can implement to support children who have experienced ACEs?

Burke Harris: One of the most important things is education and resources for families. I had one 3-year-old patient who had failure to thrive. Her previous pediatrician had provided PediaSure supplementation but hadn’t screened for ACEs. But when we screened her, she had seven ACEs. Even though this child had no behavioral issues, we prescribed parent-child psychotherapy. The therapy includes both the parent and the child and really helps the parent understand how to provide that safe, stable and nurturing environment for their child, and recognizing if the parent has ACEs how to prevent that intergenerational transfer to the child.

By adding the parent-child psychotherapy, along with the nutritional supplementation, that child went from not growing to getting back on the growth curve. Even though the child was not having behavioral problems, her body was making stress hormones. This treatment was teaching mom and working with the family to reduce the child’s stress hormones that would allow her to grow again.

Resources