Resident Program - Case of the Month

January 2018 - Presented by Dr. Ananya Datta Mitra (Mentored by Dr. Alaa Afify)

The correct answer is A.) Carcinosarcoma (Malignant Mixed Mullerian Tumor, MMMT)

Discussion

Carcinosarcoma (Malignant Mixed Mullerian Tumor or MMMT)

Uterine carcinosarcoma (malignant Mixed Mullerian tumor, MMMT) is an uncommon uterine tumor that accounts for less than 5% of uterine malignancies and typically occurs in elderly women. Risk factors include prior tamoxifen therapy, unopposed estrogens and pelvic irradiation (10- to 20-year time interval).[1, 2] These tumors are increasingly thought of as carcinomas that demonstrate sarcomatoid differentiation,[3-5] although many gynecologists continue to classify them as sarcomas. Nevertheless, they are extremely heterogenous and clinically highly aggressive neoplasms. Due to this heterogeneity they are very difficult to identify. WHO defines carcinosarcoma as neoplasm composed of an admixture of malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components.

Clinical Features

The mean age of patients presenting with endometrial carcinosarcoma is in the 7th decade, but usual age ranges from 4th-9th decades. Patients usually present with vaginal bleeding, but may have symptoms related to a pelvic mass or metastatic disease. Given that carcinosarcomas are, in essence, of epithelial derivation, they are staged as endometrial carcinomas; this is explicitly stated in the 2009 FIGO staging system for endometrial carcinomas.[6] The 5-year survival for carcinosarcoma is around 30% and the 5-year survival in surgical stage 1 disease (confined to the uterus) is approximately 50%.[7-9] This highly aggressive profile is in contrast to other high grade endometrial cancers where 5 year survivals in stage 1 disease are approximately 80% or better.

There have been numerous studies to define the prognostic factors in carcinosarcoma, however, surgical stage is the most important prognostic indicator. Other factors that have been proposed are presence of heterologous elements, grade of carcinomatous and sarcomatous components, the percentage of tumor demonstrating sarcomatous differentiation, the depth of myometrial invasion and the presence of lymphovascular invasion.[3, 5, 10]

Morphology

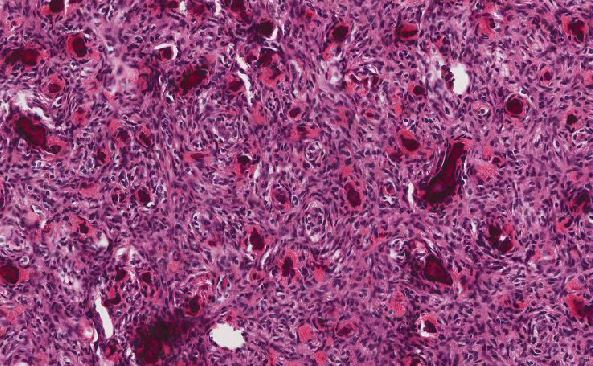

Grossly, carcinosarcomas are often bulky, necrotic and hemorrhagic polypoid tumors, which fill the endometrial cavity and may protrude through the cervical os. There may be deep myometrial invasion and cervical involvement. Occasionally, they are confined to an endometrial polyp.[11, 12] A histological diagnosis of carcinosarcoma depends on identifying high-grade malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components typically showing a sharp demarcation between both, although occasionally this demarcation may be indistinct. The epithelial element may include serous, grade 3 endometrioid, clear cell and undifferentiated carcinoma in order of frequency. Admixtures may be seen and typing of the epithelial component may be difficult; in some cases, a hybrid morphology (with features of serous and endometrioid carcinoma) or a malignant squamous component is present, which may be a clue to the diagnosis. The mesenchymal component can be homologous or heterologous. The former is typically a high-grade sarcoma and eosinophilic hyaline globules are frequently noted. If heterologous elements are present, then rhabdomyoblasts or malignant cartilage is the most common. Osteosarcomatous and liposarcomatous differentiation may rarely occur. On occasion, carcinosarcomas are associated with a component of primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET); in such cases, markers such as neurofilament, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP) and synaptophysin may be useful in highlighting this component, which is more analogous to a central than a peripheral PNET without EWSR1 gene rearrangement.[13] Occasional examples of a yolk sac tumor component and melanocytic differentiation have also been reported.[14, 15]

The relative proportions of epithelial and mesenchymal components vary widely; thus, extensive sampling in an undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma may reveal areas diagnostic of carcinosarcoma. Uncommonly, carcinosarcomas have a low-power growth pattern, which mimics an adenosarcoma; however, this is usually a focal finding, there is no stromal condensation, and the epithelium and the stroma are overtly malignant at high-power magnification. In general, immunohistochemistry is of limited value in the diagnosis of carcinosarcoma as both malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components should be seen on morphological examination. However, immunohistochemistry may be useful in confirming the presence of a heterologous mesenchymal component which, as discussed earlier, is an adverse prognostic indicator in stage I neoplasms.

Histogenesis

Although previously regarded as a subtype of uterine sarcoma, it is now well established that most carcinosarcomas are epithelial neoplasms that have undergone sarcomatous transformation, the epithelial component being the driving force; as such, they can be considered as akin to metaplastic or sarcomatoid carcinomas.[4, 10] In fact, it would be more logical to include carcinosarcoma among the subtypes of uterine epithelial malignancies rather than within the mixed epithelial and mesenchymal neoplasms and certainly these should no longer be regarded as subtypes of uterine sarcoma. There are multiple lines of evidence for its epithelial origin, including a pattern of spread that is similar to that of other ‘high grade’ uterine carcinomas with rare exceptions and that morphologically the tumor within lymphovascular channels and metastatic sites usually comprises the epithelial, or much less commonly, a mixture of the epithelial and mesenchymal components rather than the sarcoma.[5] There is also experimental evidence that most carcinosarcomas are monoclonal neoplasms rather than representing collision tumors.[16, 17] p53 expression is usually concordant between the epithelial and mesenchymal components exhibiting a diffuse, null or wild-type pattern of expression, thus suggesting a common lineage for the two components.[17] Occasionally, the sarcomatous component only manifests itself in the metastasis or recurrence of a high-grade endometrial carcinoma.

Differential Diagnosis

Tumors that may raise problems in the diagnosis of uterine carcinosarcoma include:

- Endometroid adenocarcinoma with spindle cell elements versus carcinosarcoma : In this tumor, the endometroid elements, fuse indiscernibly with spindle cell elements, that are never high grade histologically. In most cases the endometroid component is no more than FIGO grade 2 and the spindle cell component is cellular and occasionally mitotically active, but not markedly atypical. In contrast carcinosarcoma contains easily distinguishable, high-grade epithelial and mesenchymal elements. However, it is to be remembered that endometroid carcinomas can contain chondroid and osteoid elements and the presence of heterologous elements by themselves do not signify carcinosarcoma.

- When considering a diagnosis of undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma within the uterus a carcinosarcoma should always be excluded; in such cases, extensive sampling in the hysterectomy specimen may reveal diagnostic areas of carcinosarcoma. Thus when dealing with a biopsy or curettage composed only of high-grade sarcoma, not otherwise specified (NOS) or rhabdomyosarcoma, it is appropriate to render a descriptive diagnosis and state in a note that the differential includes a carcinosarcoma in which the carcinomatous component has not been sampled.

- “Dediffrentiated” endometrial carcinoma vs carcinosarcoma

“Dediffrentiated” endometrial carcinoma is described as a well to moderately differentiated endometroid adenocarcinoma juxtaposed with an undifferentiated carcinoma.[18, 19] Undifferentiated carcinoma is an uncommon, but not rare, neoplasm included in the WHO classification of endometrial carcinomas.[18-20] It is defined as ‘a tumor composed of medium or large cells with complete absence of squamous or glandular differentiation and with absent or minimal (<10%) neuroendocrine differentiation’. It may occur in pure form or in combination with and probably as a result of dedifferentiation in a low-grade (grade 1 or 2) endometrioid adenocarcinoma. Misdiagnosis of dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma as a carcinosarcoma may occur, given the characteristic sharp demarcation between the two components with the undifferentiated carcinoma being misinterpreted as undifferentiated sarcoma. In the former, the epithelial component is low grade whereas in carcinosarcoma, if endometrioid, it is typically high grade. The undifferentiated component in dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinoma usually is composed of non-cohesive cells and is typically positive, albeit typically very focally, with cytokeratins and epithelial membrane antigen (EMA); even when there is only focal positive staining with these markers, it is characteristically intense. Undifferentiated endometrial carcinomas and dedifferentiated endometrioid adenocarcinomas may be associated with mismatch repair (MMR) abnormalities, which is not usually the case with carcinosarcomas, although there is loss of staining in as much as 6% of tumors in one study.[21]

Points to Remember

- On histologic examination, the diagnosis of carcinosarcoma is made in the presence of high-grade malignant epithelial and mesenchymal components typically showing a sharp demarcation.

- Carcinosarcomas should be staged similarly to endometrial carcinomas and not using uterine sarcoma staging systems as their pattern of carcinomas.

- Percentages and types of the epithelial and mesenchymal elements should be included on the pathology report.

- In stage I uterine carcinosarcomas, adverse prognostic indicators include serous and clear cell morphology and the presence of a heterologous mesenchymal elements.

- Extensive sampling in an undifferentiated sarcoma or pleomorphic rhabdomyosarcoma may reveal areas diagnostic of carcinosarcoma.

References

- McCluggage WG, Abdulkader M, Price JH, et al. Uterine carcinosarcomas in patients receiving tamoxifen. A report of 19 cases. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society 2000;10:280-284.

- Seidman JD, Kumar D, Cosin JA, et al. Carcinomas of the female genital tract occurring after pelvic irradiation: a report of 15 cases. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists 2006;25:293-297.

- Bitterman P, Chun B, Kurman RJ. The significance of epithelial differentiation in mixed mesodermal tumors of the uterus. A clinicopathologic and immunohistochemical study. The American journal of surgical pathology 1990;14:317-328.

- McCluggage WG. Uterine carcinosarcomas (malignant mixed Mullerian tumors) are metaplastic carcinomas. International journal of gynecological cancer : official journal of the International Gynecological Cancer Society 2002;12:687-690.

- Sreenan JJ, Hart WR. Carcinosarcomas of the female genital tract. A pathologic study of 29 metastatic tumors: further evidence for the dominant role of the epithelial component and the conversion theory of histogenesis. The American journal of surgical pathology 1995;19:666-674.

- Pecorelli S. Revised FIGO staging for carcinoma of the vulva, cervix, and endometrium. International journal of gynaecology and obstetrics: the official organ of the International Federation of Gynaecology and Obstetrics 2009;105:103-104.

- Silverberg SG, Major FJ, Blessing JA, et al. Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed mesodermal tumor) of the uterus. A Gynecologic Oncology Group pathologic study of 203 cases. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists 1990;9:1-19.

- Yamada SD, Burger RA, Brewster WR, et al. Pathologic variables and adjuvant therapy as predictors of recurrence and survival for patients with surgically evaluated carcinosarcoma of the uterus. Cancer 2000;88:2782-2786.

- George E, Lillemoe TJ, Twiggs LB, et al. Malignant mixed mullerian tumor versus high-grade endometrial carcinoma and aggressive variants of endometrial carcinoma: a comparative analysis of survival. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists 1995;14:39-44.

- McCluggage WG. Malignant biphasic uterine tumours: carcinosarcomas or metaplastic carcinomas? Journal of clinical pathology 2002;55:321-325.

- Rossi A. [Carcinosarcoma (malignant mixed Mullerian tumor) arising in an endometrial polyp. Report of a case]. Pathologica 1999;91:282-285.

- Kahner S, Ferenczy A, Richart RM. Homologous mixed Mullerian tumors (carcinosarcomal) confined to endometrial polyps. American journal of obstetrics and gynecology 1975;121:278-279.

- Euscher ED, Deavers MT, Lopez-Terrada D, et al. Uterine tumors with neuroectodermal differentiation: a series of 17 cases and review of the literature. The American journal of surgical pathology 2008;32:219-228.

- Amant F, Moerman P, Davel GH, et al. Uterine carcinosarcoma with melanocytic differentiation. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists 2001;20:186-190.

- Shokeir MO, Noel SM, Clement PB. Malignant mullerian mixed tumor of the uterus with a prominent alpha-fetoprotein-producing component of yolk sac tumor. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc 1996;9:647-651.

- de Jong RA, Nijman HW, Wijbrandi TF, et al. Molecular markers and clinical behavior of uterine carcinosarcomas: focus on the epithelial tumor component. Modern pathology : an official journal of the United States and Canadian Academy of Pathology, Inc 2011;24:1368-1379.

- Wada H, Enomoto T, Fujita M, et al. Molecular evidence that most but not all carcinosarcomas of the uterus are combination tumors. Cancer research 1997;57:5379-5385.

- Altrabulsi B, Malpica A, Deavers MT, et al. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium. The American journal of surgical pathology 2005;29:1316-1321.

- Silva EG, Deavers MT, Bodurka DC, et al. Association of low-grade endometrioid carcinoma of the uterus and ovary with undifferentiated carcinoma: a new type of dedifferentiated carcinoma? International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists 2006;25:52-58.

- Silva EG, Deavers MT, Malpica A. Undifferentiated carcinoma of the endometrium: a review. Pathology 2007;39:134-138.

- Hoang LN, Ali RH, Lau S, et al. Immunohistochemical survey of mismatch repair protein expression in uterine sarcomas and carcinosarcomas. International journal of gynecological pathology : official journal of the International Society of Gynecological Pathologists 2014;33:483-491.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director