Resident Program - Case of the Month

March 2018 - Presented by Dr. Trevor Starnes (Mentored by Dr. Karen Matsukuma)

Discussion

Gangliocytic paragangliomas are neoplasms usually found in the periampullary duodenum, as in this case. Though considered rare, the true incidence of gangliocytic paraganglioma is unknown and if catalogued would probably be underestimated. In a small Japanese study, 40% of duodenal tumors originally diagnosed as neuroendocrine tumors were actually gangliocytic paragangliomas.

This patient was asymptomatic, but symptoms can include melena, bowel obstruction, and abdominal pain. While the malignant potential of the tumor is considered low, a small subset (24 case reports out of approximately 200) of tumors have metastasized to lymph nodes, liver, or bone. Fortunately, no deaths due to metastatic spread have been reported. Risk of metastasis appears to be correlated with depth of invasion and size of tumor, but is not known to be related to histologic features such as cell type proportions or Ki-67.

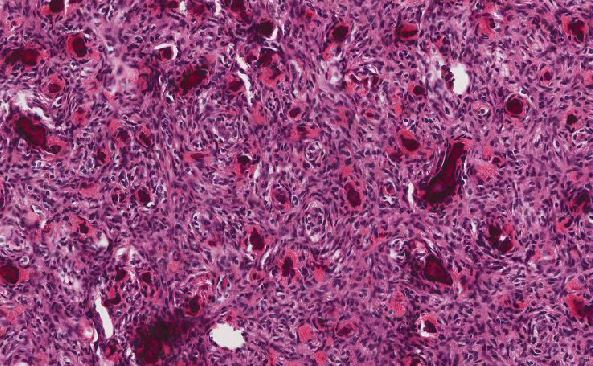

Gangliocytic paragangliomas are differentiated from similar entities by the presence of three characteristic cells types: Neuroendocrine epithelioid cells, spindled cells with nerve sheath appearance, and ganglion cells. A diagnostic challenge lies in the fact that the proportions of these cell types vary. Often the epithelioid cells are prominent while the spindled and/or ganglion cells are scarce, which explains why it may be misdiagnosed as a neuroendocrine tumor.

Examples of other tumors in the differential diagnosis of gangliocytic paraganglioma include ganglioneuroma and gastrointestinal stromal tumor. These will be more serious considerations when the epithelioid endocrine component is less apparent than in the present case. Ganglioneuromas will include a spindle cell proliferation and ganglion cells similar to gangliocytic paraganglioma. However, they will lack the epithelioid cells, and this is the key feature distinguishing them from gangliocytic paragangliomas. Gastrointestinal stromal tumors can be epithelioid or spindled, but will lack the sustentacular pattern of S-100 staining seen in gangliocytic paragangliomas, and will also be positive for DOG-1 and CD117.

It is important for pathologists to consider gangliocytic paraganglioma as part of the differential diagnosis in duodenal tumors with neuroendocrine or spindled cells, given that management will vary by diagnosis. For example, aggressive surgical management may be indicated for neuroendocrine tumors, but not gangliocytic paragangliomas. Caution is particularly warranted for small biopsies which may not provide an opportunity to observe all three cell types.

References

Iacobuzio-Donahue, Christine A, and Elizabeth Montgomery. Gastrointestinal and Liver Pathology. Philadelphia: Elsevier/Saunders, 2012.

Loftus TJ, Kresak JL, Gonzalo DH, Sarosi GA, Behrns KE. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma: A case report and literature review. International Journal of Surgery Case Reports. 2015;8:5-8.

Okubo Y, Nemoto T, Wakayama M, et al. Gangliocytic paraganglioma: a multi-institutional retrospective study in Japan. BMC Cancer. 2015;15:269.

Park HK, Han HS. Duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma with lymph node metastasis. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016;140(1):94–98.

Wong A, Miller AR, Metter J, Thomas CR. Locally advanced duodenal gangliocytic paraganglioma treated with adjuvant radiation therapy: case report and review of the literature. World Journal of Surgical Oncology. 2005;3:15. doi:10.1186/1477-7819-3-15.

Yoichiro Okubo. Gangliocytic Paraganglioma Is Often Misdiagnosed as Neuroendocrine Tumor G1. Archives of Pathology & Laboratory Medicine: October 2017, Vol. 141, No. 10, pp. 1309-1309.

Meet our Residency Program Director

Meet our Residency Program Director