Gun Violence: UC Davis Researches Causes, Trends, Solutions

The recent string of mass shootings has once again captured the attention of the American public. The tragic shootings in an elementary school in Texas, a grocery store in New York, a church in California and locally in the streets of downtown Sacramento have many people wondering what can be done to prevent such tragedies.

Each time these incidents happen, familiar questions come up around the influence of mental health, social media, socio-economic factors, race and policies.

UC Davis LIVE took up these questions in an April 19 program with two experts from the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program:

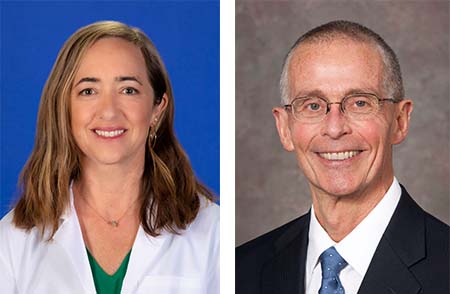

- Garen Wintemute, director of the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program and the California Firearm Violence Research Center, is a renowned expert on the public health crisis of gun violence and a pioneer in the field of injury epidemiology and prevention of firearm violence.

- Amy Barnhorst, vice chair for clinical services at the UC Davis Department of Psychiatry and an associate professor in the Department of Emergency Medicine, is a nationally recognized expert on the interface between firearms, suicide, mental illness and violence. She is the director of the BulletPoints Project, a state-funded effort to develop a firearm violence prevention curriculum for health care providers.

The following summary highlights many of the main topics discussed during the UC Davis LIVE program. Research from the Violence Prevention Research Program can be found here.

What does the data on gun violence tell us about trends?

According to our two experts, public mass shootings typically capture the public’s attention; however, they comprise only one percent of all deaths from firearm violence. The majority of deaths from firearms are suicides rather than homicides. Other kinds of firearm violence include domestic violence, unintentional injury, and more, all of which can lead to devastating consequences for the families of both victims and perpetrators and create a rippling effect in their communities.

From 2019 to 2020, the number of firearm homicides has seen an unprecedented increase, greater than any other time in the last 100 years of record keeping. Then between 2020 and 2021, the firearm homicide rate increased by 15%, resulting in an average increase of 45% across the states from 2019 to the start of 2022.

Barnhorst noted that one unexpected trend that was observed during the initial year of the pandemic was a small dip in firearm suicide rates, which had been rising in the United States over the last 17 years. This was despite the pandemic with people having to live in increased social isolation, going through a mental health decline and being concerned about illness.

Are trends in gun purchases linked to trends in firearm violence?

There was an unprecedented increase in gun purchases beginning in January 2020. The initial driver may likely have been the prospect of social unrest due to the pandemic, according to Wintemute. Other contributors followed later in the year in the form of political and racial tension and the prospect of new gun control measures following a federal election. The increase in gun purchases ended toward the end of 2021 but appears to be surging again in the spring of 2022.

The increase in gun purchasing was positively correlated with the subsequent increase in overall gun violence in the beginning of 2020, but that clear link attributed to purchasing alone was lost as the year rolled on, except for domestic violence.

Thirty years ago, there was a tight coupling between the rate of gun violence and the rate of gun purchasing, but that link disappeared about 15 years ago. One contributor may be that privately manufactured guns (“ghost guns”) came into the mix, making tracing gun ownership more difficult.

The definition of gun ownership also comes into play. Wintemute noted that it is estimated that roughly 80% of the instances of gun violence are committed by someone that is not the original, legal purchaser of the gun.

In addition, data indicates that about 40% of the people committing gun homicides are not prohibited from purchasing firearms. Lack of enforcement of existing laws has resulted in federal agencies like the military not reporting events even though they are required to.

How effective are background checks?

The evidence is mixed on the effectiveness of universal background checks to reduce rates of firearm violence. Establishing this link is difficult because the available data don’t always support rigorous research designs. It appears that effectiveness is increased by adding a permitting process, according to Wintemute.

What makes a community more vulnerable to gun violence?

There are several interconnected factors that make a community more vulnerable to gun violence. According to Barnhorst, it is important to examine social components that shape individual lives within the community. For example, she noted the importance of access to safe parks, schools and healthcare as well as employment opportunities and affordable housing. These key influencers are often governed by socio-economic and environmental factors — creating a self-perpetuating cycle — often more prevalent in marginalized communities where discrimination has taken a toll. Due to a lack of alternatives, these communities often become hotbeds for gun violence and substance abuse. Barnhorst said the key to preventing gun violence lies in early intervention, and not waiting until the last minute to pass some legislation.

How can we reduce the risk within specific communities of need?

In recent research by the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program, a large number of Californians reported having some experience with firearms violence. These include hearing gunshots in their neighborhoods, encountering sidewalk memorial to violent deaths or learning about violent events on social network. According to Barnhorst, investing early in people’s lives through schools, parks, neighborhood spaces and job opportunities can all add up to violence prevention. For example, people who have the privilege of growing up in safe spaces with a lack of stress, abuse and trauma grow up to be emotionally resilient and respond better to crises than individuals on the opposite side of the spectrum.

Wintemute voiced optimism about our collective capacity to bring about change. He urged people not to give up hope. “If you see something, say something,” he said. In 80% of cases, he said, people who commit mass shootings or slide into suicidal acts make their intentions known in advance either to family members or friends or via social media. In such cases, there’s always an opportunity to intervene. “We can’t turn away from one another,” he concluded.

Barnhorst and her team have developed a curriculum for healthcare providers to raise awareness about potential risk situations. Clinicians are encouraged to have conversations on how firearm violence affects their patients, who is at risk, what are the ways they can identify the risk, access to guns and more.

For example, if someone has a child at home or living with an adolescent or any person with alcohol abuse or a mental health condition, they should have an open discussion about safe storage so at-risk individuals don’t have immediate access to firearms during the times these individuals go through an emotional crisis. Barnhorst also recommended in some circumstances moving the firearms away from the house temporarily to prevent harm.

Resources