Mock drill prepares UC Davis nursing students for public health emergencies

A pregnant woman. An older adult with dementia missing their caregiver. A son, with his father, separated from his mom, the only English-speaking member of the family.

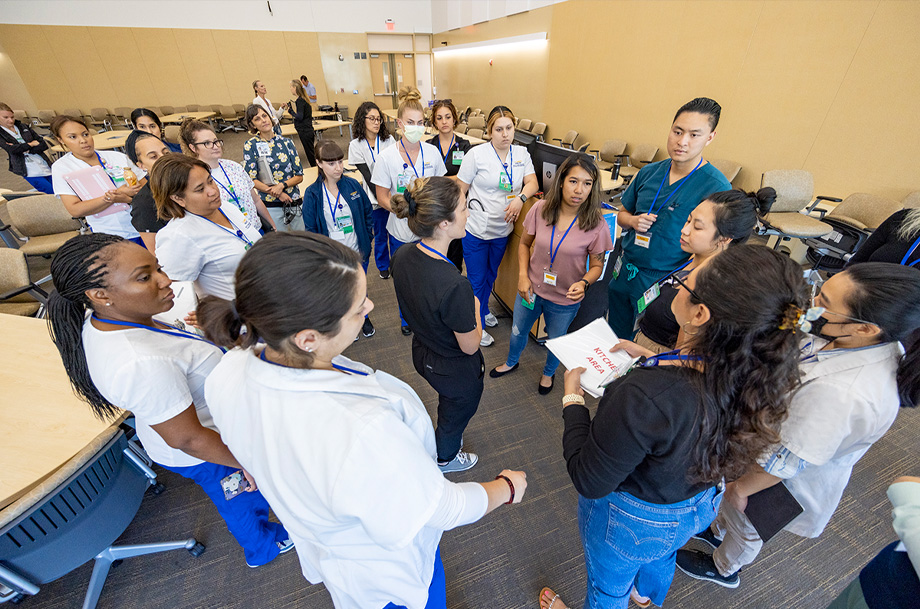

These evacuees recently visited a staged shelter set up at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at UC Davis earlier this week. But they were not actually experiencing these scenarios. They were role-playing in a mock drill for students in the Master’s Entry Program in Nursing.

The experience is part of the School of Nursing’s Nurturing Healthy Communities course for students with only two quarters left before they complete their 18-month program. Instruction emphasizes working with diverse communities in providing health promotion, chronic disease management, transitional support and crisis intervention.

“The simulation is designed to give them some exposure to what it's like to be nurses at an evacuation shelter. It’s a really important function of public health nursing to support disaster response. Yet this isn't really something that we often do a lot of training about in schools,” said Jennifer Edwards, course instructor and the school’s simulation director.

Edwards and a team of faculty, patient actors and community partners from public health departments in the area staged a triage tent outside Betty Irene Moore Hall and a nearby classroom to serve as the shelter. Students played the roles of shelter administrators, triage nurses, evacuees and emergency operations center staff leading the emergency effort and getting resources.

School of Nursing clinical nurse educator Cindy Wilson says she wishes she had this type of training in school.

“The very first time I had to set up a shelter, I didn’t even know that was my job. I didn’t know what it meant in a practical sense,” admitted the former director of nursing for the public health department in Nevada County, Calif. “With this four-hour simulation, they’ll have four hours more training than I did.”

Clinical care takes back seat

Mock drills are designed to test providers on how prepared they are to handle an emergency like a fire, flood, earthquake or any such incident that causes injury and death. But this is not typical disaster training. While many exercises focus on the obvious injuries — a burn, broken limb or open wound — this creates an opportunity for students to triage community members whose other needs make them particularly vulnerable.

“Students are using their clinical knowledge and broadening it in a real-world scenario,” Edwards explained.

That includes the very real risk of infection prevention and need for control. Students must set up procedures to combat the spread of infectious diseases like COVID-19 or norovirus. They need to consider who needs medication, where they can get it and who can wait for care. They practice communications skills to compassionately reassure those most at risk and who are marginalized in society.

“Having never experienced this before, it was it was an eye opener because so many people come from different backgrounds. You don't really know what resources they have available until they tell you or you ask them questions,” said student Erica Stansfield. “I think in some ways I learned a lot from asking more about the patients. I really enjoyed connecting with them and making sure that they were OK.”

After the first 45-minute disaster management portion of the drill, students took a quick break and then simulated closing the shelter. They had to consider the many challenges of returning residents back to the community safely, which teaches them case management and medication consideration skills.

“It was fun, a little chaotic,” explained student Kristy Phal. “It showed me a lot because there were issues popping up during the event of the simulation and we had to think quick on our feet.”

Community assessment drives simulation

The experience of the students mirrors the reality of nurses who practice in rural areas and how they provide care for people with a wide range of conditions including chronic diseases, mental health challenges and maternal health. So, the School of Nursing looked to its community partners to learn what they wish students knew prior to entering the workforce.

“In public health, our clients are the community. We may do one-on-one client care, but in the large scheme we’re trying to move the needle to increase the health of the population of our community,” said Char Weiss-Wenzl, director of public health nursing for the Nevada County Public Health Department.

A $500,000 grant from the Health Resources and Services Administration, funded the Public Health Nursing — Empowering Nurses, Teaching Rural care Using Simulation Training project. With those funds, Associate Dean for Practice Deb Bakerjian asked leaders from county public health departments and rural and underserved Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to identify gaps in nursing knowledge and skills in public health.

“Students don’t get enough time or exposure to the realities of public health in most nursing schools. This beautifully highlights how academics can partner with the community to try and meet the needs they have,” Bakerjian said.

“My hope from this experience is that, at the very least, they think about the humanity of their patients. Don’t get caught with blinders on regarding immediate medical needs. Think about the social determinants of health,” Weiss-Wenzl added.

Bakerjian plans to leverage project findings to create a toolkit and simulations that others can benefit from. while hope is that the grant will strengthen the future public health nursing workforce by building students’ interest and skills, this week students left the experience with a new perspective on how to be resourceful when resources are scarce.

“The shelter environment asks them to use their critical reasoning, their clinical knowledge and bring it all together,” Edwards said. “If they're in this experience in real life, they've had an opportunity to sort of work through those feelings in a safe place."