Reality bite: How a tiny insect reshaped one scientist’s research and family life

Epidemiologist Kristen Aiemjoy discovered firsthand the dangers of an understudied infectious disease when her son got sick

In the middle of the night, Kristen Aiemjoy woke to screams. She hurried to her 8-year-old son Zavi’s room. He was having a violent night terror. His skin was flush with fever.

After administering Tylenol and applying a damp washcloth to his forehead, she finally got him back to sleep.

It was August 2023 in Bangkok, Thailand. Zavi, whose name has been changed for privacy, had recently returned from a hiking adventure with his grandfather. They had trekked through the jungles of Kaeng Krachan National Park in the southern part of the country, near the border of Myanmar. He had complained of a headache the previous day, which Aiemjoy had chalked up to dehydration.

Then again, his legs had been covered in bug bites.

Aiemjoy knows better than most the risks posed by certain insects. An assistant professor of epidemiology at the UC Davis School of Medicine, she spends part of each year studying the infectious diseases common to Southeast Asia, such as malaria and dengue fever. Aiemjoy specializes in the lesser known scrub typhus, a bacterial disease spread through the bite of an infected chigger, or tiny larval mite.

She hadn’t expected that her professional and personal lives would intersect so dramatically.

Diagnosis: Scrub tyhpus

On day three of high fever, Zavi was experiencing extreme fatigue. He could barely keep his head up during the day. He was pale. His condition was deteriorating. It was time to see a doctor.

Aiemjoy took Zavi to Mahidol University’s Hospital for Tropical Diseases, where she has an affiliation. Her colleagues drew blood to test for malaria and dengue, but results the following day proved negative. That’s when Zavi developed a cough.

Another anxious day passed. Suddenly from the couch, Zavi asked, “Mom, what’s this on my head?”

Spreading apart the hair on his scalp, Aiemjoy found a tiny, dark scab. One of the key indicators of scrub typhus is the appearance of an eschar where the chigger larva chews skin tissue and deposits the bacteria that leads to infection. They had completely missed it.

Aiemjoy immediately returned to the hospital. On the way, she emailed her mentor Stuart Blacksell, one of the worlds’ experts in scrub typhus diagnostics. The subject line read, “HELP!”

“I immediately recognized the urgency of the situation,” said Blacksell, who ordered a biopsy and a polymerase chain reaction (PCR) test that confirmed Aiemjoy’s suspicion. Her son had scrub typhus.

Clinical limitations

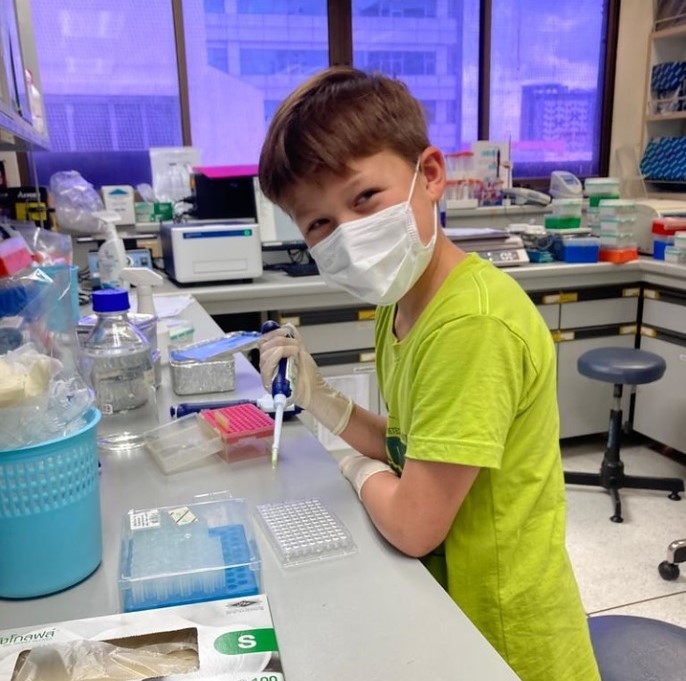

After a week of antibiotics, Zavi recovered. But his journey wasn’t over. He agreed to provide finger-prick blood samples to aid his mother’s research, which coincidentally involved measuring scrub typhus antibody responses over time.

Antibodies are proteins produced by a person’s immune system that detect harmful pathogens. The antibodies can be measured in the blood as markers of exposure before eventually decaying.

Published in The American Journal of Tropical Medicine and Hygiene and The Journal of Travel Medicine, the results of Aiemjoy’s studies showed that the best clinical scrub typhus tests can’t detect antibodies until at least 9-11 days after a patient’s fever begins.

That means when patients do seek medical care, it’s often too early to test for scrub typhus. And only 40-60% of infected patients develop a small, painless eschar (scab), which can be hard to locate on the body. The disease can easily go undiagnosed and the patient sent home untreated.

This is a very scary infection. There's really a need right now for low-cost, acute-phase diagnostics.”—Kristen Aiemjoy, epidemiologist, UC Davis School of Medicine

Scrub typhus complications can include acute respiratory distress syndrome, pneumonia, kidney or organ failure. Experts estimate the scrub typhus mortality rate is 6% without antibiotics.

“This is quite high. This is a very scary infection,” said Aiemjoy. “There's really a need right now for low-cost, acute-phase diagnostics.”

Current scrub typhus tests are expensive. For many people in regions like Thailand, Nepal and Myanmar, a $7.70 test — the cost of Aiemjoy’s research team’s tests, purchased at a discount — is completely inaccessible.

Her goal is to develop a test that would cost patients less than $2.

Disease prevalence

Scrub typhus is one of the most prevalent febrile diseases in the world, with some of the least accessible diagnostic technology.

“My personal opinion is that scrub typhus is the most understudied infectious disease that causes hospitalizations and severe illness globally,” Aiemjoy said. “In surveillance studies, it's often in the top three causes for being hospitalized with fever — up with dengue and malaria. Every time when you start looking for it, it's there.”

During the current high season for scrub typhus in the Kathmandu area of Nepal, researchers in another of Aiemoy’s studies are seeing 10-14 pediatric patients test positive for scrub typhus each week out of about 90 total weekly patients in a single hospital.

The problem is spreading. Last summer, scientists identified scrub typhus in chiggers found in North Carolina.

Yet scrub typhus isn’t even on the World Health Organization’s list of neglected tropical diseases.

“It's not something that causes a handful of people to get sick. This is a huge, huge cause of illness,” Aiemjoy explained. “And one of the reasons mortality is so high is because you just can’t get the diagnosis in time.”

Improving the diagnostic capabilities for scrub typhus buys more time, according to Blacksell. “We can ensure that patients in endemic regions receive the appropriate treatment as soon as possible, saving lives and reducing the burden of this potentially fatal disease,” he said.

He and Aiemjoy are working to provide evidence that earlier diagnosis will prevent lengthy hospital stays and save lives.

Aiemjoy remains hopeful. Splitting her time between California and Thailand, she is overseeing the work of a Ph.D. candidate who is developing a trap to catch the chiggers that spread scrub typhus. After raiding a hardware store in Bangkok, the team built an early prototype using sticky adhesive tape and a plastic soup bowl.

You work with what you’ve got, Aiemoy said. And, as in the terrifying days surrounding Zavi’s illness, what you’ve got can sometimes hit very close to home.