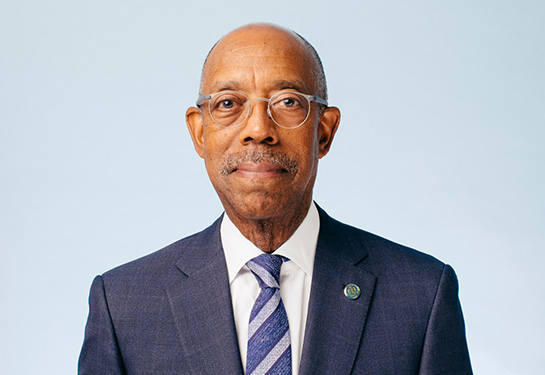

UC President Michael V. Drake: ‘It’s a great privilege to help others do well’

Drake — an ophthalmologist — talks about mentors, medicine and his hopes for the UC community

Michael V. Drake, the 21st president of the University of California, recently sat down for a Q&A with the UC Davis Eye Center. He oversees UC's world-renowned university system of 10 campuses, five medical centers, three nationally affiliated labs, more than 280,000 students and 230,000 faculty and staff.

Drake, who grew up in Sacramento, received his A.B. from Stanford University and his M.D. and residency training in glaucoma from UCSF. He subsequently spent more than 25 years on the faculty of the UCSF School of Medicine, ultimately as the Steven P. Shearing Professor of Ophthalmology and senior associate dean.

Your first summer job in the early ’70s was at the original Tower Records in Sacramento. What was that like?

I loved working at the record store. All my high school friends would come by to visit. We could play any record in the store, anytime. This was before streaming services, so if you wanted to hear certain music, you had to own it or wait all day to hear it on the radio. We were among a small number of people in the world who could listen to any record, at any time. It was a great way to spend the summer.

What music did you listen to then, and what do you listen to now?

A musician I listened to then — and who I listened to this morning, driving to work — was Miles Davis. My friends at the record store played rock-and-roll all day. You could always tell when it was my turn to play something because you'd hear Miles. To find new music now, I watch whoever is performing on “Saturday Night Live.” They do a good job of curating bands.

What was your childhood like growing up in Sacramento, and how did that influence your decision to go into health care?

My mother worked as a social worker at the county hospital — what is now UC Davis Medical Center. My father was a psychiatrist and was also involved in family practice primary care. What was known as general practice, back in the day. I knew my father worked hard at taking care of people, and that it meant a lot to him. I grew up thinking that was a normal thing to do.

I had severe asthma when I was growing up. I missed half of first grade due to my asthma. My father kept epinephrine for me in the refrigerator, with syringes that my parents would boil on the stove. It sounds archaic, but it was like a little ER. When I would have to wake him up in the middle of the night because I couldn’t breathe, my father never minded. He would just pop up out of bed and take me downstairs. He would give me the medication, and a minute later, I was better.

So, I learned two important things subliminally as a child. One is that it is a privilege to help people when they are in need. And second, that medicine could work and really could make people feel better.

How did you select ophthalmology for your residency?

I was one of those medical students who liked every specialty I rotated through. Ophthalmology, though, combined the problem-solving of medicine with the technical interventions of surgery. It was a great balance of those two things. In my rotations, I met people in the ophthalmology department who were great mentors and whom I still know today.

What influenced your choice of glaucoma as a subspecialty?

In medical school, I liked physiology as a way of thinking and approaching problems. Glaucoma is a physiologic disease that has surgical and medical interventions, so it had a lot of the things I was interested in. I also liked the public health demographics of glaucoma. Glaucoma is an addressable disease where we can make a real difference in people's lives with modern medicine.

Did you want to work in higher education when you began medical school?

Going to medical school and having a practice was my plan. What changed my mind was doing research as a medical student. One day during a general conversation about life and my future plans, one of my faculty research advisors, Dr. George Brecher, said, “You should think about an academic career. You could see patients, do research and teach. All the things you like doing — all together.” A few years later, during residency, I asked one of my professors, Dr. Dunbar Hoskins, Jr., about the long-term effects of a cyclo-cryotherapy procedure we did back then for intractable glaucoma. He said, “That's a great question. We don't really know the answer to that. You should do a study.”

I said, “Okay,” and set up a clinical study. I presented the results at our departmental alumni meeting. People were receptive. It put it in my mind that when you have a question that no one has the answer to, you can study it. I never realized you could do that or that it was an option until I met people who were doing it.

What excites you most about vision science at UC Davis and other UC institutes?

It’s been great to see the direction ophthalmology has moved. It is technically more sophisticated and has also focused on the visual care of broad populations.

For example, the field has been focused on the public health ramifications of visual disability, visual loss, and visual impairment while working to uplift communities broadly, working more on preventive care.

Dr. Carol Mangione from UCLA has done really great work in looking at the public health impact of visual impairment and ways that we might lean into that.

A friend and former resident, Dr. Robert Weinreb from the Shiley Eye Institute at UC San Diego, has done a lot of work on psychophysics, diagnostics, and being able to measure the way the visual system is performing and to monitor it.

Dr. Jamie Brandt, from UC Davis, identified the predictive value of central corneal thickness measurements in glaucoma. Around the world, central corneal thickness measurements are another critical part of protecting the vision of patients with glaucoma.

These are just a few examples of some UC-centric work that has informed the way that we deal with eye disease worldwide.

What’s the significance of having the Ernest E. Tschannen Eye Institute in Sacramento?

We have several wonderful eye institutes in the UC system that have done a great job. They have each become a world-connected center for vision research and advancing ophthalmology. It's terrific for this to be the case at UC Davis as well. UC Davis has had a great eye department for many years. Having an institute in the Sacramento area will help the community take that next step forward.

In September 2021, you visited the UC Davis Health campus. You attended the investiture ceremony for Dr. Paul Sieving as the inaugural holder of the Neil and MJ Kelly Presidential Endowed Chair in Vitreoretinal Science. What about that visit stood out for you?

I remember the sense of community. Many friends and committed, connected people came together for the first time since the pandemic started to celebrate the gift created for the Eye Center. Many faculty at the Eye Center have been my colleagues and friends since the very beginning of my career.

Dr. Sieving has had a tremendous impact on vision care and vision science. He was considering many different institutions. We were pleased and proud that he chose UC Davis. It was wonderful to have him inducted as the inaugural chairholder and to be able to celebrate the donors. The event was wonderful from all points of view.

As president of the University of California, how have you seen philanthropy influence the trajectory of our mission?

One of my great mentors, Dr. Lloyd Hollingsworth “Holly” Smith from UCSF, said something to me about 15 years ago. I was doing a recruitment for a dean, and we were walking across the street. Holly had an aura. If it were a movie, he'd have a little glow around him. As we were walking, he patted me on the shoulder and said, “Just remember that the difference between A and A+ is huge.”

As a university, we can get to the A level in many things on our own. But sometimes, it takes a little boost to get from A to A+. And often that boost comes from philanthropy. Our supporters investigate and determine areas where a financial boost can turn that next step into that next leap.

What does it mean to you that donors like Ernest Tschannen and Neil and MJ Kelly make significant philanthropic investments to departments such as the UC Davis Eye Center?

The philanthropists that I've worked with are very thoughtful people. They think carefully about where they want to make their investment, and they want it to make a difference.

I feel like we are partners in helping to make the world a better place in a meaningful way. It is among the real rewards of being in this kind of work to say that individuals can make a difference in the quality of life and the quality of the community that they live in.

What is your greatest hope during your tenure as president of the University of California?

I am fascinated by the different directions we're moving. It's great to see the number of nationally and internationally significant contributions being made broadly across the University of California. I think the UC Davis Eye Center will facilitate many of these contributions.

The University of California is a very large community of 500,000 people. The goal is to facilitate each of them fulfilling their human potential. And that goes for our students, staff and faculty. I want to help create circumstances for people to excel. Like I learned from my father, it’s a great privilege to help others do well.

Resources