Lipoprotein(a): A less understood but critical risk factor for heart disease

Endocrinology researchers investigate impact of diet on lipoprotein(a) levels

UC Davis Health endocrinology researchers are taking aim at a less understood but critically important risk factor for heart disease: lipoprotein(a), or Lp(a).

The group is doing a study funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) on the non-genetic influences of Lp(a) concentrations. They recently published research on this topic in the journal Atherosclerosis to address the under-researched aspects of Lp(a) regulation.

An elevated level of lipoprotein(a) is a prevalent risk factor for cardiovascular disease. Genetic factors play a major role in Lp(a) concentrations. In fact, Lp(a) levels are 70% to 90% genetically determined.

Racial differences in Lp(a) concentrations have also been well documented. Black individuals are more likely to have elevated Lp(a) than white, Hispanic or Asian individuals.

“While Lp(a) levels are mostly regulated by genetics, there is evidence of extensive variability in Lp(a) levels between individuals and groups that cannot be fully explained by genetic factors alone,” explained Enkhmaa Byambaa, professor of endocrinology, diabetes, and metabolism at UC Davis Health. “For this study, we set out to examine the potential role of non-genetic influences on Lp(a) levels.”

What is lipoprotein(a) and why does it matter?

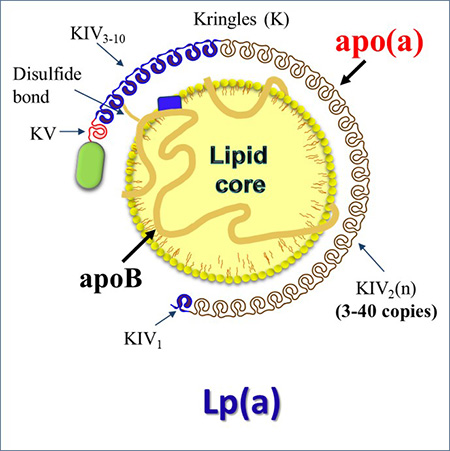

Lipoproteins include low-density lipoprotein (LDL-C), high-density lipoprotein (HDL) and Lp(a), among others. While most people know that LDL-C, or “bad” cholesterol, can cause heart disease, fewer people know about the potential risk posed by Lp(a).

It is estimated that up to 20% of people worldwide have high levels of Lp(a), which is associated with a risk of heart attack or other serious cardiovascular events.

“A patient’s Lp(a) levels are one of the strongest indicators of their genetic risk for cardiovascular disease,” Byambaa explained. “Despite the association between Lp(a) and cardiovascular disease, it flies under the radar. It is not as well-understood as other risk factors and current tests are not well standardized.”

Because Lp(a) particles vary in size, commonly used lab tests are not ideal. Physicians and researchers specializing in this field have called for the development of more accurate, standardized tests that measure Lp(a) levels in nanomoles per liter instead of milligrams per deciliter.

“The better we can understand the nature of lipoprotein(a) and the more precise testing methods we can develop, the more we will be able to help physicians better identify high-risk patients. This will also support the research into the mechanisms underlying the link between lipoprotein(a) and heart disease,” Byambaa said.

-wb.jpg)

Non-genetic influences on Lp(a) concentrations

In their paper, the researchers reviewed current evidence and studies on non-genetic factors influencing Lp(a) levels. They paid particular attention to diet, physical activity, hormones and certain pathological conditions. They found that strong, consistent evidence suggests that:

- Replacement of dietary saturated fat with protein, carbohydrates or unsaturated fat increases Lp(a) levels by 10–15%.

- Hormone replacement therapies of androgens and estrogens impact Lp(a) levels. This is in contrast to the body’s sex hormone levels under non-pregnant conditions.

- Both hyperthyroid and hypothyroid conditions modestly impact Lp(a) levels.

- Lp(a) levels increase with chronic kidney disease and nephrotic syndrome.

- Lp(a) levels are associated with hepatocellular damage – a decrease is seen with disease progression. Whether non-alcoholic fatty liver disease influences Lp(a) remains unclear.

“Our findings on non-genetic influences on Lp(a) concentration indicate a role for diet, hormones and liver and kidney diseases,” Byambaa said. “However, more data is needed to firmly establish any potential role for other factors, such as physical activity, exercise, and certain liver diseases.”

The better we can understand the nature of lipoprotein(a) and the more precise testing methods we can develop, the more we will be able to help physicians better identify high-risk patients. This will also support the research into the mechanisms underlying the link between lipoprotein(a) and heart disease.” —Enkhmaa Byambaa, associate professor of endocrinology, diabetes and metabolism

The connection between lipoprotein(a), diet and saturated fatty acids

Byambaa and her team have been awarded a four-year, $2.5 million NIH grant to continue studying the impact of dietary changes on Lp(a) levels.

Lifestyle modifications, including dietary changes, are recommended to patients as a first-line therapy to reduce cardiovascular disease risk. Guidelines recommend patients lower their intake of saturated fatty acids and replace them with unsaturated fats or complex carbohydrates.

“A reduction in saturated fatty acid in a patient's diet has been shown to decrease LDL-C,” Byambaa explained. “However, in the small number of human clinical trials that assessed Lp(a) level, a consistent increase was found in response to a reduction in saturated fatty acid intake – a counter observation to the effect on LDL-C.”

For their study, the researchers will assess the changes in Lp(a) properties in response to a reduction in saturated fatty acid. They’ll examine the impact of the diet change on proatherogenic and proinflammatory oxidized phospholipids, which are carried in Lp(a). Research suggests that oxidized phospholipids play an important role in atherosclerosis - the buildup of fats, cholesterol and other substances in and on the artery walls.

“Our hope is this study will assist us in adopting precision nutrition as part of a heart-healthy lifestyle for a more holistic cardiovascular disease risk prevention and management tool,” Byambaa said.