The gift of life: A father and son's transplant journey

UC Davis Health performs its first living donor liver transplant

Andy Wright remembers the morning he woke up from anesthesia after his liver transplant.

His wife, Carie Wright, was beside him in the UC Davis Medical Center’s Intensive Care Unit. Within minutes of speaking, she noticed something had changed.

“Andy smiles again,” she said.

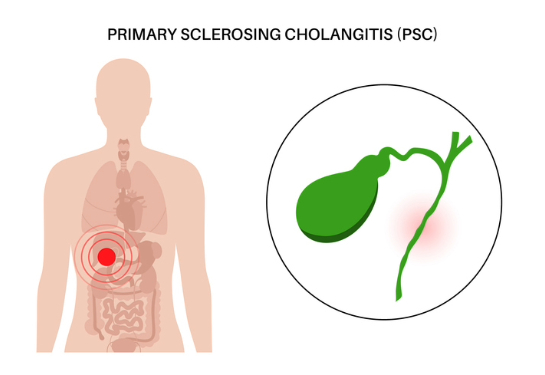

In 2008, while serving on US Air Force active duty, Andy was diagnosed by Michael J. Krier, chief of gastroenterology at David Grant Medical Center at Travis Air Force Base, with primary sclerosing cholangitis (PSC). The condition is a rare, chronic liver disease in which the bile ducts become inflamed and scarred, eventually causing liver damage, and potentially leading to liver failure. Krier referred Andy to the UC Davis Health hepatology team.

Andy’s health remained stable for years but began to decline rapidly about two years ago. He lost 50 pounds and battled a range of debilitating symptoms, including portal hypertension, esophageal varices, encephalopathy (brain fog), malaise, persistent leg cramps and ascites.

“Each day, I felt like I was just trying to survive,” Andy recalled.

Despite having low MELD (Model for End-Stage Liver Disease) scores, a common challenge for PSC patients, Andy was referred for a liver transplant by his hepatologist, Christopher Bowlus, chief of Gastroenterology and Hepatology at UC Davis Health.

Exploring the path to transplant

When Andy and Carie met with the transplant team at UC Davis Health, they learned that the waiting period for a typical liver transplant — in which the organ comes from a deceased donor — could range from less than 30 days to over five years.

To potentially shorten this wait, the team explained the option of a living donor liver transplant, a procedure in which a healthy person donates a portion of their liver to someone in need. This is possible because the liver is uniquely capable of regeneration: Both the donor's and recipient's livers can grow back to full size within a few months after surgery.

“I didn't realize a partial liver transplant was even an option,” Andy shared. “But I was hesitant. I didn't want to put any of my family or friends at risk.”

However, the Wright family was deeply concerned, too — about Andy. They could see how desperately he needed a new liver.

Without telling anyone, his son, Nick Wright, quietly went to get screened to see if he might be a match.

“One day, I had a really bad feeling I just couldn't shake,” Nick recalled. “So, I decided to start the process. He needed it done.”

After undergoing a thorough evaluation, Nick learned he was eligible to donate a portion of his liver to his father.

Andy, initially, didn’t like the idea.

“When Nick first told me he wanted to donate part of his liver, I was apprehensive,” said Andy. “A few days after Nick told me he wanted to save my life, my close friend Bruce Watts — who also happens to be Nick's boss — encouraged me to let Nick do this and to trust him. Between my family, close friends and the transplant team, I was convinced that Nick wanted to do it for the right reasons, and I could not deny him his choice to help me.”

The power of living donation

Living donor liver transplants are significantly less common than those from deceased donors in the United States. Not everyone qualifies for a living donor transplant, as the recipient must be healthy enough to thrive with only a portion of a liver.

Typically, candidates for living donor transplants have a lower MELD score compared to those awaiting a deceased donor organ, and their anatomy must be suitable for the procedure.

“In Andy’s case, he was an ideal candidate for a living donor liver transplant,” explained Lea K. Matsuoka, section chief for liver transplantation and hepatobiliary surgery at the UC Davis Transplant Center. “His MELD score was low, and he was in a condition where receiving a transplant early could prevent his health from deteriorating further.”

For the donor, safety is paramount. They must not be at increased risk for surgical complications. Physicians carefully evaluate the donor's liver size and anatomy to ensure it's appropriate for the recipient and can be safely divided. In addition, medical teams thoroughly assess the donor's overall health and liver function.

“The safety of the donor is always our top priority,” added Matsuoka. “They're giving this gift out of the goodness of their heart, and we want to make absolutely sure nothing happens to them.”

“The safety of the donor is always our top priority. They're giving this gift out of the goodness of their heart, and we want to make absolutely sure nothing happens to them.” —Lea K. Matsuoka

Father and son make transplant history

Andy and Nick underwent surgery on July 15, with close family in the waiting room. Some relatives were even flown in from Oregon, thanks to the efforts of Bruce Watts, so they could be there to support the family during the procedure.

During the procedure, surgeons removed Andy's failing liver. Andy then received the entire right lobe of Nick's liver — approximately 60% of the whole liver — while Nick retained his left lobe. In most cases, the liver regenerates in both the donor and the recipient within six to eight weeks.

The procedure was the first-ever living donor liver transplant performed at the UC Davis Transplant Center. Only a small number of transplant centers across the United States offer this complex and highly specialized procedure.

“This transplant marks a historic milestone for our center and a tremendous step forward in expanding access to life-saving care,” said Sophoclis Pantelis Alexopoulos, medical director for the Transplant Center and chief of abdominal transplant surgery. “It was made possible by the extraordinary dedication, skill and collaboration of our entire transplant team. I'm incredibly proud of everyone who helped bring this to life.”

“This transplant marks a historic milestone for our center and a tremendous step forward in expanding access to life-saving care.”—Sophoclis Pantelis Alexopoulos

Healing begins

Within hours of the procedure, Andy felt better than he had in over 10 years, despite the pain associated with recovering from surgery. When tested, his liver panels were nearly normal for the first time in two decades.

“It’s the little things you don't even notice,” he said. “I hadn't slept more than four hours a night in two years because of severe leg cramps. I used to get terrible abdominal pain, bouts of physical weakness, and my memory was trash. It's incredible to feel like I have my brain back.”

Andy was deeply grateful for his care at UC Davis Medical Center.

“The transplant team is incredible. They don't just treat you; they educate you and explain why they're doing what they do,” he shared. “For them, patient care is the priority. They're genuinely good people, doing this work for the right reasons. They're masters of their craft.”

He added: “I am forever grateful for Nick's selfless act, my wife Carie and daughter Megan's support throughout, the incredible transplant team's excellence, my family's caring and close friends’ empathy.”

A selfless gift

Nearly a week after the procedure, Nick walked down the hospital hallway and visited Andy. Both were scheduled to be discharged that day.

“It’s nice seeing him return to his old self,” Nick reflected at his dad’s bedside. “It's a huge relief for my entire family.”

Andy and Nick are looking forward to a healthier future and spending time together.

“We've got some plans,” Nick said with a smile. “It's exciting to have him back and to know he’ll be with us for a long time.”

When asked what advice he’d give to someone considering organ donation, Nick shared, “Donating part of your organ is a big decision, but when it's for someone you love, there’s no hesitation. I'd do it all again.”

How UC Davis is changing lives through transplant care

Inspired by Andy and Nick's story? Discover how the UC Davis Transplant Center is transforming lives through innovative care, compassionate support and world-class expertise.

Whether you're considering organ donation, exploring transplant options, or simply want to understand more, visit the UC Davis Transplant Center’s website to learn how to take the next step.