Defying the odds: Recovery of a teenage stroke survivor

A 17-year-old boy receives life-saving neurological care at UC Davis Medical Center

It was two weeks after Thanksgiving and 17-year-old Joshuah Sanchez had just come home from high school wrestling practice in Galt. He was winding down for the evening when he began to feel dizzy. He assumed it was the beginning of another epileptic seizure, like the ones he’d had before, but seconds later he felt the worst headache of his life.

“That’s when I knew something was off, and so I called to my mom to call 9-1-1,” Sanchez recalls. “After that it was all kind of a blur, but I remember being transported to a hospital.”

Paramedics administered morphine for the headache with no results. Upon arrival at Lodi Memorial Hospital, the attending physician suspected something abnormal and ordered a CT scan. The scan confirmed bad news: Sanchez had experienced a subarachnoid hemorrhage. That means there is bleeding due to a ruptured brain aneurysm, specifically in a fluid-filled space between the brain and the skull.

He was quickly transferred to UC Davis Medical Center, a destination hospital for stroke patients from 33 counties.

Young stroke patients

Strokes in teenagers are relatively rare but can have devastating consequences. Doctors realized Sanchez had a ruptured terminal left internal carotid artery aneurysm.

“This aneurysm needed to be treated because it can rupture again,” recalled Ben Waldau, a neurosurgery professor at UC Davis who oversaw Sanchez’s care at the medical center. “Typically, the second time such an aneurysm ruptures is fatal.”

This aneurysm needed to be treated because it can rupture again. Typically, the second time such an aneurysm ruptures is fatal.” —Ben Waldau

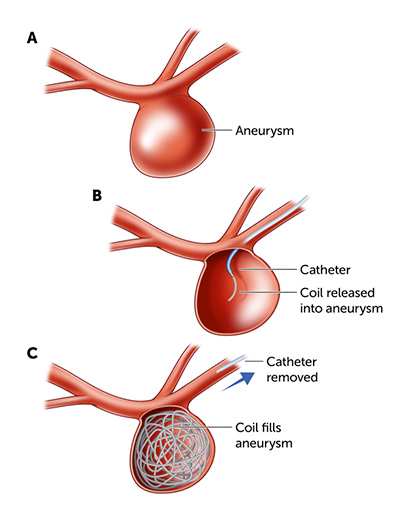

An aneurysm is the bulging of an artery that begins as a weak spot that balloons out and can subsequently rupture. While a ruptured aneurysm in a survivor may only bleed for a few seconds before closing off again, the aneurysm poses a high risk of bleeding again if untreated.

There are two common ways to treat an aneurysm.

The most common, known as coiling, is the least invasive. With coiling, providers insert a light, flexible coil through the blood vessels of the arm or groin and allow it to coil inside the ballooned portion of the affected artery. This helps a blood clot form inside the ballooned portion, thereby preventing another bleed.

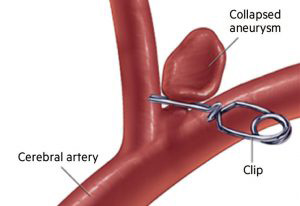

The other treatment requires surgery to open the head and skull to expose the aneurysm. Surgeons then close off the ballooned area with a metal clip which has tines that are about 2 to 20 mm long.

“The advantage of clipping is that the treatment is more durable,” Waldau said. “Clipping lasts longer than coiling. With coiling, he would need to be screened every year with imaging and possibly retreated since about 20% of aneurysms come back after coiling in the short term. This percentage may be even higher in pediatric patients with ruptured aneurysms.”

Waldau decided to clip the aneurysm since it would be the least disruptive to Sanchez’s lifestyle in the long term, given that he was only 17.

“In my experience, especially in pediatric cases, aneurysms can come back after coiling, perhaps because their aneurysmal walls are more unstable than in adults,” Waldau continued. “This is where the value of microsurgical clipping as definitive therapy comes in. With clipping, the aneurysm almost never comes back, and I only screen every 10 years.”

Twenty-one days after the surgery, Sanchez walked out of the hospital and went home to Galt.

By January, he had begun attending classes again.

Despite some challenges with short-term memory, Sanchez continued the school year, crediting support from his mom, teachers, and peers. He attended prom in April and graduated from Liberty Ranch High School last Friday.