Smarter homes, smarter care: How a nursing professor is shaping the future for older adults

Professor Roschelle “Shelly” Fritz's smart home research and global nursing summit are shaping the future of aging-in-place technology

Roschelle “Shelly” Fritz remembers it like it was yesterday. While working as an emergency department nurse in Boise, Idaho, a patient came in that would change the trajectory of her life.

“Mr. Smith,” she calls him to protect his identity, arrived by ambulance. The 79-year-old was in and out of consciousness with extremely low blood sugar. A concerned neighbor had found him unconscious, slumped over in his recliner in his home — a Life Alert button hanging around his neck.

“When I asked him, ‘Mr. Smith, you weren't feeling good. Why didn't you push your Life Alert button?’ And he said, ‘What? What button?’ – He didn't even remember it was around his neck,” she recalled. “That was the straw that broke the camel's back for me.”

Fritz knew technology was evolving rapidly and being used effectively in other fields like transportation and banking. She wanted to harness it in nursing care to improve patients’ lives.

She embarked upon a Doctor of Philosophy in Nursing Science Degree from Washington State University, where she paired up with a computer scientist in the field of artificial intelligence (AI). They started designing a smart home hoping to create and train an algorithm to recognize clinically relevant behavior changes occurring at home.

Fritz advanced her technology as a fellow with the Betty Irene Moore Fellowship for Nurse Leaders and Innovators. She then joined the School of Nursing faculty to further advance her work in a supportive and more diverse environment. The school’s work with the Healthy Aging in a Digital World initiative and Family Caregiving Institute provided a place where her work and knowledge could be leveraged to keep older adults independent.

Lifesaving monitors you don’t know are there

Today, Fritz develops health technologies that use AI to monitor people’s well-being at home, helping them stay independent longer. Her work focuses on detecting early signs of health problems before they turn into emergencies, reducing the need for hospital visits. The goal is to support older adults in aging at home rather than moving to higher levels of care.

“It’s a simple idea. When you don't feel well, you move differently. And we think we can automate recognition of that and allow the technology to work alongside humans in the health care system, and the family and patient, to be able to understand when a health event is either happening or about to happen,” explained Fritz, now a professor at the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing at UC Davis.

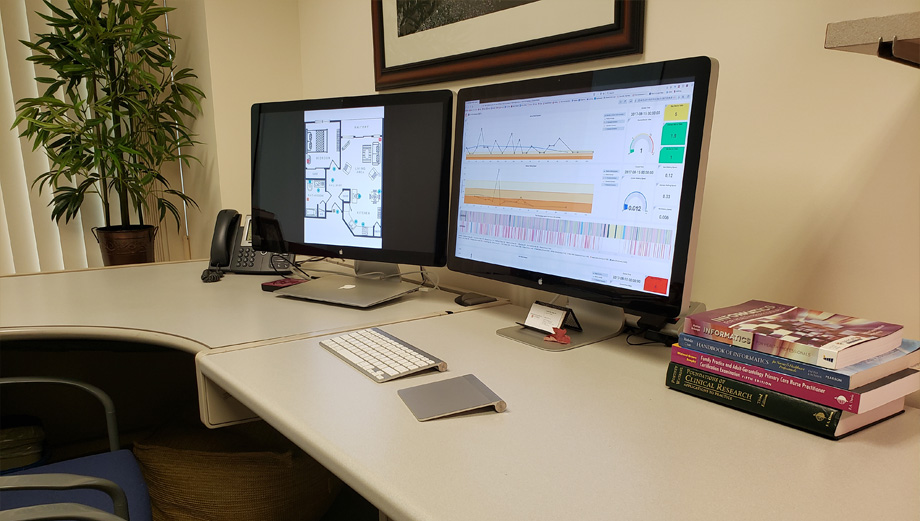

Fritz’s lab is called SAGE (Smart Aging and Gero Environments). It is pioneering a unique approach to health monitoring by using AI-driven data analysis. Researchers monitor passive infrared, light, temperature, humidity and door-use contact sensors — without cameras or microphones — to track how people move within their house. By establishing patterns and tracking deviation in those patterns, researchers can determine behaviors that are directly correlated to health.

“This sensor data is ambient, unobtrusive and does not require the older adult to interact with it at all,” she added.

The lab has deployed the technology in 100 homes of older adults enrolled in studies lasting from six to 24-month. Data collected recognizes 11 common activities of daily living with greater than 98% accuracy. In addition to the sensors and machine learning models, which have proven capable of accurately recognizing certain changes in health states, nurses conduct telehealth visits with the study participants.

“Nurses gather real-world health updates, providing crucial context that helps engineers train algorithms to detect meaningful changes in health status. We bridge cutting-edge AI with real human insights to spot health changes early — because the best care happens before a crisis,” she said.

Committed to technology and older adults

“Dr. Fritz’s experience, expertise and passion for developing creative and minimally invasive technology solutions to promote health for older adults aligns so well with both the initiative and institute,” said Heather M. Young, national program director of the Betty Irene Moore fellowship. “Dr. Fritz is a seasoned clinician who can inform design in a way that assures that older adults and caregivers benefit the most from her innovation to advance their goals to thrive at home.”

Studies suggest that 75% of older adults overwhelmingly want to stay in their homes. But nearly half of them do not believe they will be able to because of the increasing needs and risks that come with age. That’s where aging-in-place initiatives, like the one Fritz is developing, come into play.

“Since this field is rapidly evolving, isolated efforts, like mine, can’t keep up with the pace of innovation,” Fritz explained. “I believe that other nursing scientists working in technology and aging must collaborate. By sharing insights, validating research and developing care models that integrate technology, we can make solutions more effective, user-friendly and aligned with the needs of both patients and caregivers.”

By sharing insights, validating research and developing care models that integrate technology, we can make solutions more effective, user-friendly and aligned with the needs of both patients and caregivers.—Professor Roschelle “Shelly” Fritz

A global gerontology center for nursing science

Fritz will host a two-day workshop in Betty Irene Moore Hall March 12-13, 2025, with the goal of creating a global gerontology center for nursing science where scholars from different countries can connect and share ideas faster than through traditional research publications. She recognizes that technology in health care evolves quickly and waiting for studies to be published can slow progress. This international center would give nurses working on futuristic care models a dedicated space to collaborate, support each other and advance research that benefits older adults worldwide.

“We want the Betty Irene Moore School of Nursing, in which this global center will be housed, to be the hub of the organization. Then spokes will go out to different countries where others are working on health technology and nursing care models to position us for what it looks like in the future, especially for nurses,” Fritz said. “In my opinion, nurses are going to be the health data brokers of the future.”

Fritz received a $14,000 seed grant from UC Davis Global Affairs, which supports work that is fostering collaborations to advance groundbreaking discovery with global partners.

What if?

As Fritz seeks more grant funding and growing her collaboration circles, her “why’” for this work remains “Mr. Smith.”

She argues that had he lived in the smart home she’s developing, the AI would have alerted his routine was off, perhaps signaling a deviation from his custom of getting into bed at night. A family member or community health worker could have been notified.

“He lived alone and nobody found him until the next morning, when he didn't pick up his paper off the sidewalk. He had a Life Alert but didn’t remember. But what if we’d been able to intervene earlier in the process,” she questioned.

“We aim for our algorithm to recognize health changes in real time and in ways that are just as sophisticated and accurate as our country’s nuclear and transportation industries. We should be able to do this for older adults.”