Study finds caregiver-child relationships improved after seven-session intervention

Challenging behaviors improved, communication increased after PC-CARE

Only about 25 percent of children with challenging behaviors receive mental health treatment, and dropout rates are high for those who do. This makes brief and effective intervention programs to improve relationships between children and their caregivers needed.

A growing number of open trials (clinical trials in which both the researchers and participants know which treatment is being administered) and comparison studies have supported the use of Parent-Child Care (PC-CARE), a seven-session intervention program developed at the UC Davis CAARE Center.

A new study by researchers at UC Davis Children’s Hospital uses the first randomized controlled trial to evaluate PC-CARE’s effectiveness for children with challenging behaviors and their parents or caregivers. The study design randomly assigns participants to an experimental or control group and is often referred to as the gold standard in research. The study’s findings were recently published in the Journal of Child Psychiatry Human Development.

“Many families struggle with managing challenging child behaviors, but it is difficult to find behavioral health support. Because PC-CARE is brief and able to be conducted in many locations, it may allow providers to help more families in a shorter amount of time,” said Brandi Hawk, a co-developer and supervisor of PC-CARE and the principal investigator of the study. “As the first randomized controlled trial of PC-CARE, these findings are necessary for solidifying PC-CARE as an evidence-based treatment.”

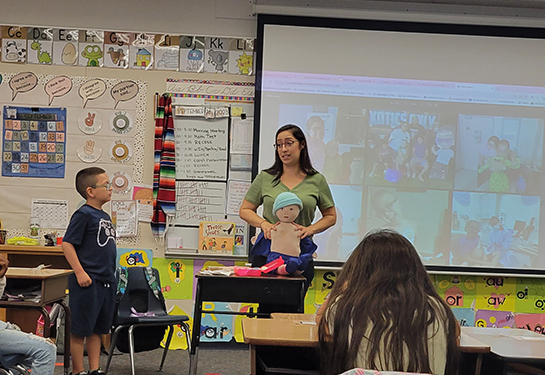

Helping children and their caregivers through lessons, coaching

In this study, primary care pediatricians referred 102 children to the study from Sept. 2018 to March 2020. Study participants were referred from two pediatric clinics within the university health system.

To be included in the study, participants:

- Were 2-10 years old

- Had one participating primary caregiver who lived with the child at least 50% of the time

- Were pediatric patients within a university health system

- Had family that was able to participate in services in English

- Had challenging behaviors, as reported by the caregiver

From those referrals, the parents or caregivers of 49 eligible children agreed to participate in the study, attended an initial assessment and were randomly assigned to either a treatment group or a waitlist group (which was the control group).

For those in the treatment group, PC-CARE treatment consisted of six weekly, 50-minute treatment sessions. Children and their caregivers participated in all sessions. Sessions consisted of the following:

- Caregivers completed a form, measuring their child’s behavior. Therapists conducted a brief check-in about the week with caregivers and the children.

- Therapists taught a 10-minute lesson on positive communication, calming skills and behavior management skills to caregivers and children. New skills were taught each week and built upon each other.

- Therapists conducted a four-minute observation of the child and caregiver playing together, coding the caregivers’ use of five specific positive communication skills known as PRAISE (which stands for praise, reflections, imitations, behavioral descriptions and enjoyment).

- Praise: A positive evaluation of the child, including both nonspecific (e.g., “Nice!”), and specific praise (e.g., “Nice work playing gently with the toys!”).

- Reflections: Repetition or rephrasing the child’s appropriate verbalizations (e.g., Child: “I’m building a house.” Parent: “You are building a house.”).

- Imitation: An overt statement indicating that the caregiver is following the child’s lead (e.g., Parent: “I’m driving my car just like you.”).

- Behavioral Descriptions: A non-evaluative description of the child’s behavior (e.g., “You are drawing a rainbow.”) or progress toward goals (e.g., “You are really concentrating.”).

- Enjoyment: A verbal expression of positive feelings about the current situation that would not be considered praise (e.g., “I’m having fun playing with you.”).

- While therapists did teach and coach parents to use the PRIDE skills, they equally focused on teaching other regulation and behavior management strategies to help the family find which strategies work best for them in different situations.

- Therapists coached caregivers to use the skills within the context of play for 20 minutes.

- Therapists reviewed accomplishments made by the caregiver and child in session, assigned 5 minutes in play daily and encouraged them to use attained skills throughout the day.

Families placed on the waitlist received no PC-CARE services and were contacted after six weeks to attend another assessment and begin treatment.

Study therapists provided services at either a pediatric primary care clinic or an outpatient mental health clinic associated with the same university health system. Each family’s schedule and preference dictated where their sessions were held.

Many families struggle with managing challenging child behaviors, but it is difficult to find behavioral health support. Because PC-CARE is brief and able to be conducted in many locations, it may allow providers to help more families in a shorter amount of time.”—Brandi Hawk

Communication, behavior improvements in seven weeks

After seven weeks, study findings showed that:

- Parents reported that children’s behavior improved.

- Caregivers demonstrated improvements in their positive communication skills.

- Caregivers reported less parenting stress after completing treatment.

- Caregivers doubled their total number and proportion of PRIDE skills from pre- to post-treatment, whereas caregivers in the waitlist, or control group did not.

“These findings provide evidence that PC-CARE may increase access to services by addressing the attrition, length and location barriers of other parenting interventions,” said Hawk, who noted that their seven sessions had an 81 percent retention rate. “While other effective interventions exist, they are often time consuming, have high attrition rates and may not be easily adapted to different site locations.”

Hawk added that there is a need for effective interventions that can keep families engaged.

“These study findings show that PC-CARE offers notable benefits to both children and caregivers in seven short weeks,” Hawk said.

The study was funded by a grant from the Children’s Miracle Network at UC Davis.

The study’s co-authors were Susan Timmer, Lindsay Armendariz, Deanna Boys, Anthony Urquiza and Erik Fernandez y Garcia, of UC Davis Children’s Hospital.