Global team of scientists discover a new gene causing severe neurodevelopmental delays

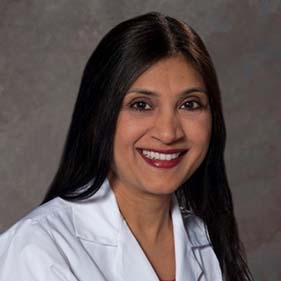

An international team of researchers led by UC Davis geneticist Suma Shankar has discovered a new gene implicated in a neurodevelopmental condition called DPH5-related diphthamide-deficiency syndrome. The syndrome is caused by DPH5 gene variants that may lead to embryonic death or profound neurodevelopmental delays.

Findings from their study were published in Genetics in Medicine.

“We are so excited about the novel gene discovery,” said the lead author Suma Shankar, professor in the Departments of Pediatrics and Ophthalmology and faculty at the UC Davis MIND Institute. Shankar is the director of Precision Genomics, Albert Rowe Endowed Chair in Genetics, and chief of Division of Genomic Medicine.

DPH5 is essential for protein biosynthesis. It belongs to a class of genes needed for the synthesis of diphthamide, a type of modified amino acid histidine, critical to ribosomal protein synthesis.

“We provide strong clinical, biochemical and functional evidence for DPH5 as a cause of embryonic death and major neural dysfunctions. Disruption to the work of DPH5 impacts multiple body systems and organs, including the heart,” Shankar said.

Parents with DPH5 variants now know that the chance of having a child with the disorder is one out of four. They may elect to do prenatal genetic testing before or during pregnancy.”—Suma Shankar

Collaborations spark discoveries

UC Davis led this project, with collaborations from across the world. Scientists from Germany, Saudi Arabia, Sweden, Massachusetts and California worked together to uncover this new gene.

The project started with an office visit. In 2018, Shankar saw a Syrian family with two kids showing severe neurodevelopmental delays in the precision genomics clinic. The parents who are blood related were interested in genetic testing to understand what was causing their kids’ symptoms. The analysis showed one specific gene, DPH5 with a ‘variant of uncertain significance’.

Shankar posted the variant on the GeneMatcher website to try to find other families with DPH5 variants. The program identified two families: one in Massachusetts and the other in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia. The Undiagnosed Disease Network Program had performed genome sequencing for the family in Massachusetts.

In total, the study discovered specific DPH5 variants in five kids showing neurodevelopmental delays. The youngest was 11 days old and the oldest was 10. Three were female and two were male. They had distinct head and facial features, profound disabilities, abnormalities in their hearts and feeding difficulties.

“We could say that the changes in the gene are likely disease-causing variants,” Shankar said.

Developing a DPH5 mouse model

As soon as Shankar and the team found the gene variant in the first family, they started working on a targeted mouse model. In collaboration with the UC Davis Mouse Biology Program, they developed a model with an altered DPH5 gene mimicking changes found in the first family.

The DPH5 variant on both copies of the gene in the mouse model proved to be deadly. Only one mouse was born alive but it died 24 days later. It showed impaired growth, head and facial deformation, and multisystem dysfunction, similar to that in humans.

“We had to create several mouse models with several generations. Yet, we were able to develop just one very small mouse with distinct craniofacial features,” Shankar said.

Testing the variant in human and yeast cells

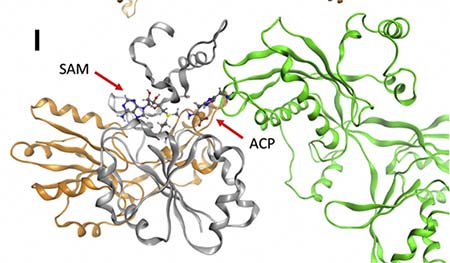

The team also studied the effects and interactions of the DPH5 variants in human and yeast cells. Working with researchers at Roche in Germany, they found that DPH5 variants in human and yeast cells led to absent or low DPH5 functioning.

In addition, the team worked with Swedish experts to perform computer simulation modeling of the variants. The simulations showed altered DPH5 structure and disruption of its interaction with eEF2, a protein essential for other protein synthesis.

Research supporting family decision making

The study expands the knowledge on diphthamide-deficiency syndromes and diseases related to ribosomal protein production. In the era of precision medicine and targeted therapies, knowing the underlying genetic causes of the disease may impact the care of individuals with such neurodevelopmental delays.

“Now, we can start thinking about studies to better understand the physiology of the disease and to determine the function of the DPH5 gene,” Shankar said.

The study showed that this is an autosomal recessive disorder. It means both parents must carry the gene mutation to have a child with a DPH5-related condition.

“Parents with DPH5 variants now know that the chance of having a child with the disorder is one out of four. They may elect to do prenatal genetic testing before or during pregnancy,” Shankar said.

This research was supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH) grants (U01HG007690, U42 OD012210) and DFG Priority Program 1927 'Iron-Sulfur for Life' and Children’s Miracle Network grant in Pediatric Genetics.