Angelica Martin: The health policy whisperer

Fourth-year medical student provides classmates with the know-how to change laws to benefit the underserved

The messages from classmates first started to flash across Angelica Martin’s phone screen during health policy lectures early on in medical school.

Whenever the professor dove deeper into weighty topics such as federal legislation, the notifications intensified. Martin had quickly become the go-to, first-year student who could explain in rapid-fire typing – in real time– things they may have forgotten from their high school civics class.

She loved to untangle policy discussions and help classmates understand how new rules and regulations can benefit the medically underserved.

Then, barely four months into her first year at UC Davis School of Medicine, she took her passion one step further: Martin created a resourceful elective for students to better comprehend their policy-based curriculum. She named her course First Aid for Health Policy.

The course is one of many innovative accomplishments by Martin, an aspiring surgeon in her fourth year of medical school.

“Just like when I was younger and served as a bridge between the field of medicine and my community,” said Martin, a former teenage Spanish-English hospital interpreter, “I realized I had the knowledge and language to serve as a bridge between the field of health policy and my medical school peers.”

She added: “These are good and smart students who have the capacity to change things. They want to change things.”

Martin is on a mission to show them how.

Childhood in Los Angeles includes first-hand experience with poverty

Martin spent her childhood in Echo Park, a low-resource, predominantly Latino community outside downtown Los Angeles.

She observed her widowed mother, an immigrant from Nayarit, Mexico, negotiate with landlords to accept Section 8 housing vouchers. She spent countless hours in community clinic waiting rooms for one of the few specialists willing to accept Medi-Cal to treat her brother’s bronchitis.

In high school, she volunteered at the local Good Samaritan Hospital, often the only Spanish speaker in the emergency department and a vital link between physicians and patients. Such as the time when she relayed to a young woman with abdominal pain that her baby would be fine – except the patient had no idea she was pregnant.

Martin built empathy, trust and comfort by using precise intonations and body language appropriate to the patient’s culture.

“I didn’t know it at the time,” Martin recalled, “but I was helping Good Samaritan provide what is commonly called ‘culturally competent care.’”

Martin attended Belmont High School, where she noticed that few students went on to college. Wanting to see better opportunities, she brokered a deal with the administration to launch an Advanced Placement chemistry class – the school’s only college-level science course.

She relies on a self-proclaimed stubborn streak, and pure grit, to prove others wrong. Like when a high school music teacher implied that girls were too small to take a leading role in the jazz band, because he always assumed they couldn’t sustain notes as long as boys.

Martin practiced extra hard to prove him wrong, and it paid off. She won the role of lead alto saxophonist. The teacher apologized.

“Just because it hasn’t been done,” Martin likes to say, “doesn’t mean it can’t be done.”

College years further opened her eyes to health inequities

Her academic drive impressed the Gates Millennium Scholars Program, which awarded her a full ride to Wellesley College in Massachusetts, a private, liberal arts campus for women. That’s where a public health course opened her eyes to inequities that further influenced her desire to be a doctor.

As an undergrad, she co-founded Proyecto Doctoritas, a community health program in Guatemala that promotes immunization and access to primary care providers.

“What I think is beautiful about public health done right is that it’s community-led,” Martin said. “I also grew to appreciate why understanding public health would help me to more effectively address all the systematic health disparities that I’d witnessed since I was a little girl.”

She graduated with two degrees – biology and women’s and gender studies – then moved down the interstate to Boston University for its renowned Master of Public Health program.

What she experienced in the middle of the program was life changing.

Martin was seeking an internship required for her masters when a friend encouraged her to apply for a position with the powerful LA County supervisor, Gloria Molina. Martin, however, was repulsed at the idea. “That’s politics,” she told her friend. “Politics has nothing to do with public health.” Besides, Martin argued, “politics is messy.”

Nevertheless, she took the internship.

Advocating for the underserved and studying for the MCAT

To her surprise, the temporary job taught Martin that politics, public policy and advocacy are critical components needed to improve the health of the underserved.

Now she was hooked on advocacy.

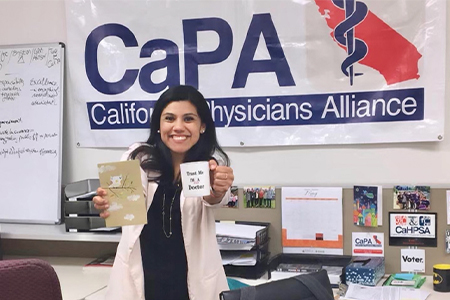

Martin returned to Boston to finish her MPH, then accepted a full-time position in Molina’s office until the supervisor was termed out. Martin then took a job at California Physicians Alliance, or CaPA, a group that represents progressive doctors in favor of universal health care. During the day she would help students create CaPA chapters across the state, while at night she would study for the Medical College Admissions Test (MCAT).

Eventually she was promoted to associate director of CaPA. She also continued to study for – and take, and retake – the MCAT.

She later made the decision to quit her job and focus on getting into medical school. Martin was accepted into the full-time, post-baccalaureate premed program at UC Davis. The arduous program, which offers biology curriculum and MCAT preparation skills, is attractive to disadvantaged students and makes them more competitive applicants for med school.

After finishing the post-bacc and a stint as CaPA executive director, Martin was accepted to the UC Davis School of Medicine. It was a perfect match for a student eager to take part in the school’s culture of reducing health disparities. That, plus, all the advocacy opportunities at the Capitol just three miles away.

“I wanted to be somewhere where they would support me to become the physician I wanted to become,” she said.

She understands how broken the health care system is. And she understands, because of her background in health care, that policy is really a lot of the reason why the health care system is broken.”—Erik Fernández y García, associate professor of clinical pediatrics

A surprising revelation after enrolling at UC Davis School of Medicine

When Martin sat through her first health policy class, she noticed many classmates looked lost on basic political science facts.

Some students didn’t know how a bill becomes law, while others didn’t understand the structure of the health care system. Martin was happy to share her knowledge over messages and in hallways. But she wanted to do more.

She vented to her academic coach, Erik Fernández y García. She told him the School of Medicine could benefit from an introductory policy course like the ones she led for CaPA on college campuses, which motivated students to advocate for the underserved.

Fernández y García offered a simple response: “OK, why don’t you do that here?”

And, just like that, she put together a syllabus, shared it with the Office of Medical Education and received approval to create MDS 484: First Aid for Health Policy.

“I think it’s great that she identified a need and didn’t just complain but actually created something in a scholarly way,” said Fernández y García, an associate professor of clinical pediatrics. “She understands how broken the health care system is. And she understands, because of her background in health care, that policy is really a lot of the reason why the health care system is broken.”

First Aid for Health Policy is a lecture series in the beginning of the school year that brings some of California’s leading health care experts, as well as those from the UC Davis School of Medicine to eight lunch-hour sessions. The next series starts Sept. 1.

Featured speakers have included Sandra Hernández, the president of the California Health Care Foundation; Anthony Wright, executive director of Health Access; and Glennah Trochet, the former Sacramento County Health Officer.

Some of the lecture topics are: “How a bill becomes law,” “Our current healthcare system,” “The structure of government,” and “How to conduct a legislative visit.”

Medical students receive an elective credit for attending six of the eight lectures in each series. More than 200 students have attended.

The lectures seek to train future health care leaders how to testify in front of legislators, support grassroots movements, incorporate social determinants of health into their clinical assessments and plans, and improve the health care system, especially for those who can’t easily access it.

Wright, whose nonprofit Health Access and its foundation are among the state’s principal voices for expanding Medi-Cal, calls Martin an “impressive leader” because of her passion for advocacy.

“There’s a lot of important conversations going on in the Capitol about what the health system is going to look like,” Wright said. “Medical students want to have a say – to be part of a profession and a system that is more inclusive, equitable, and more affordable.”

Wright worked with Martin, when she served as executive director of CaPA, to bring busloads of Health4All coalition advocates to the Capitol to rally for health care for every Californian, including those who are undocumented. He says Martin is part of a new generation of politically active students growing impatient with the status quo and craving change.

Martin, he said, is now at the right place, at the right time.

“UC Davis has a unique perch, being so close to the Capitol of the biggest state in the nation, to make a difference,” Wright said. “I’m glad she’s taking advantage of it with her own voice and trying to bring in her fellow students as well.”

UC Davis has a unique perch, being so close to the Capitol of the biggest state in the nation, to make a difference. I’m glad she’s taking advantage of it with her own voice and trying to bring in her fellow students as well.” —Anthony Wright, executive director, Health Access

Ambitious accomplishments during medical school

As if planning a lecture series wasn’t enough to keep Martin busy during the rigors of medical school, she’s also managed to get involved in multiple projects related to advocacy, on and off campus.

She and other students helped revive the school’s dormant CaPA chapter. She’s also been part of Organized Medicine, which is aligned with the Sacramento Sierra Valley Medical Society (for which she served as the UC Davis student representative).

She has received numerous honors and accolades, including most recently a 2022 Excellence in Public Health Award from the U.S. Public Health Service.

In addition, Martin is a scholar in TEACH-MS, the competitive UC Davis medical school pathway for students set on caring for patients in urban underserved communities.

Martin looks forward to this final year of school, when she’ll experience clinical rotations at UC Davis Medical Center and other hospitals while also interviewing for surgical residency programs. She hopes to advocate for policies that make it easier for medically underserved patients to access surgeries.

When she looks into the future, Martin sees optimism for patients in need of health care, thanks to a new generation of socially conscious doctors-to-be. “Everyone deserves to live with dignity,” she said.

She doesn’t forget where she came from. And she’s thankful for those who helped her get to where she is.

“I've been fortunate to have had mentors who modeled the act of envisioning a future that might not yet exist,” she said. “It's my goal to do the same for others."