Gastroschisis and the search for better and earlier interventions

Gastroschisis is a complex and costly birth condition that affects babies’ bowels. Cases have doubled in the United States over the last two decades.

Geoanna M. Bautista, an assistant professor of pediatrics in the Division of Neonatology at UC Davis Health Children’s Hospital, shares best practices in caring for newborns with gastroschisis.

Bautista’s research focuses on gastrointestinal diseases specific to newborns. She is especially interested in cases of prematurity and congenital anomalies that impact normal gut development, including gastroschisis. She has spearheaded the establishment of the UC Davis Baby Intestines Group (B.I.G.). It is a collaborative initiative among neonatology, gastroenterology and surgery to improve the outcomes, growth and longitudinal care of neonates at high risk for intestinal failure, such as babies with gastroschisis.

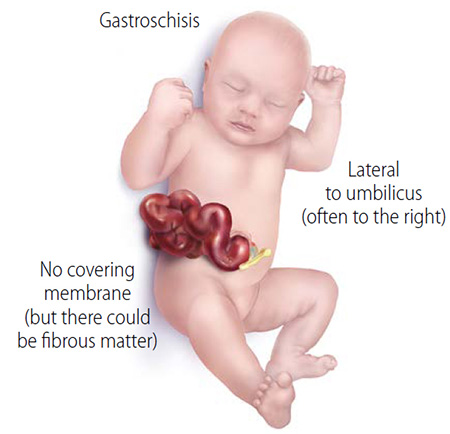

Q. What is gastroschisis?

A. Gastroschisis is an abdominal wall defect that results in impaired gut maturation and dysmotility. In this condition, the baby develops an opening in the abdomen through which their intestines spill out into the surrounding amniotic fluid.

Gastroschisis is unique in that it disproportionately affects younger mothers. It also appears to be associated with environmental factors, although the underlying causes and development are still poorly understood.

Q. When is gastroschisis diagnosed?

A. Gastroschisis is often diagnosed during the anatomy scan performed around 16 weeks gestation. In some cases, it is not found until after the baby is born, usually due to limited or no prenatal care. If diagnosed prenatally, parents typically get referred to a hospital with a level IV Neonatal Intensive Care Unit (NICU), such as UC Davis Health Children’s Hospital, that has access to specialist surgeons.

Q. What happens when babies with gastroschisis are born?

A. Babies with gastroschisis can often be delivered vaginally, which surprises most parents since the baby’s intestines are outside their body. At the delivery, it is very important that the bowel is handled with the utmost care during initial resuscitation; any compression can cause injury. The bowel being outside the body can also lead to significant fluid losses resulting in dehydration and electrolyte changes. Thus, the baby will also need a lot of fluids.

Q. How is gastroschisis treated?

A. Surgical correction of the original defect occurs shortly after birth. The babies are brought to the NICU where surgeons evaluate the defect size, the amount of bowel, and if any other organs, such as the liver, have also managed to herniate out.

Babies either get one of two repairs: A primary repair, where surgeons put the intestines back into the abdominal cavity immediately or a staged reduction, where a silo or a special plastic sheath is placed over the intestines to allow the slow return of the intestines into the abdominal wall cavity.

These babies have been developing without the intestines inside the abdominal cavity. They are already on the smaller side. After the repair surgery, there is often a prolonged monitoring period until the baby has adequate bowel function and motility. After that, we introduce and advance feeds very slowly.

Q. What are some health complications linked to gastroschisis?

A. We have come a long way in optimizing neonatal management and postnatal repair of the original defect. Yet, these babies often struggle with delayed gut motility and function due to the damage that happened in utero. Some babies may need additional surgeries to remove part of their intestines.

About 20% of babies with gastroschisis develop necrotizing enterocolitis (NEC), a disease that causes inflammation and death of tissues in the intestine. Thus, some babies may need to have part of their intestines removed due to atresia (obstruction) or from the development of NEC. This may lead to short bowel syndrome, intestinal failure and life-long challenges.

Babies that don’t require additional surgeries or resections can still have problems with dysmotility and absorption of nutrients. This can further impact their already poor growth and development.

Q. What could be driving inflammation in babies with gastroschisis?

A. We still don’t know what is driving this inflammation. Our team believes a mechanosensitive signaling pathway may be the missing link in understanding gastroschisis-related complications. More research has come to light regarding the critical role that signaling pathways play in normal development and innate immune responses to inflammation. These responses are often impaired in prematurity and babies with disorders such as gastroschisis.

This is truly an exciting time in science because we now have better tools and a greater understanding of some of the mechanisms driving the disorders in other similar disease processes. We have moved towards a more collaborative team science approach so that our efforts translate into true clinical benefit for these babies.

Q. Are there interventions that can help developing babies with gastroschisis in utero?

A. There are currently no in-utero interventions available for gastroschisis. Previous research efforts focused on decreasing inflammatory mediators present in the amniotic fluid but have failed to produce any clinical benefit. But it is now clear that something triggers this inflammatory cascade. It becomes a vicious cycle since the fetus is then producing its own cytokines and other inflammatory mediators.

So, there is growing interest in developing fetal interventions that focus on earlier, more upstream targets to hopefully prevent the ongoing damage that clearly affects normal gut development.

Thanks to Drs. Diana Farmer and Shinjiro Hirose who established the Fetal Care and Treatment Center (FCTC) and the Center for Surgical Bioengineering (CSB) co-led by professor Aijun Wang, UC Davis has truly become a hub for pioneering fetal interventions that result in truly amazing outcomes. With this kind of environment and resources, I anticipate that my current collaboration with Dr. Hirose will lead to new efforts and success at intervening in these babies before they are even born.

Bautista recently received awards from the Hartwell Foundation, the Children’s Miracle Network and the Clinical and Translational Science Center KL2 award.

Related stories:

Necrotizing Enterocolitis - Dorian's Story at UC Davis Children's Hospital