UC Davis researchers lead innovative work on KCNT1-related epilepsy

Jill Silverman and Sarah Olguin use new technology to give families hope

A UC Davis postdoctoral researcher and her mentor have received two key funding boosts to advance their leading-edge work into the rare neurodevelopmental condition KCNT1-related epilepsy.

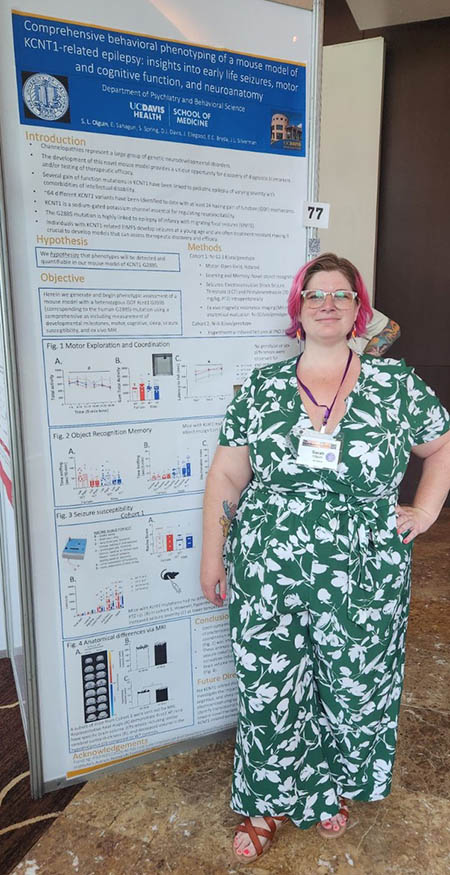

Sarah Olguin received a two-year, $100,000 fellowship from the Hartwell Foundation, a prestigious honor for early-career researchers.

She and her mentor, Professor Jill Silverman, were also chosen for a $68,667 pilot grant from the KCNT1 Epilepsy Foundation as part of the Penn Medicine Orphan Disease Center’sMillion Dollar Bike Ride campaign.

Olguin and Silverman are both in the Department of Psychiatry and Behavioral Sciences and the UC Davis MIND Institute. Silverman is known worldwide for her groundbreaking work with rodent models.

What is KCNT1-related epilepsy?

KCNT1 is a gene which regulates potassium channels in the brain. In children with KCNT1-related epilepsy, the channels are more open than they should be, which allows more ions to get through, leading to seizures and epilepsy.

The condition causes drug-resistant seizures — sometimes hundreds in a day — that affect key brain development. Children may be unable to walk, talk or eat without a feeding tube. Intellectual disability is common, and life expectancy is limited.

KCNT1-related epilepsy is rare. According to the KCNT1 Epilepsy Foundation, roughly 3,000 cases have been identified globally so far. But the foundation notes that there are likely far more people affected, as testing is still not widespread.

The work being done by Olguin and Silverman on a KCNT1 mouse model holds significant promise for these families.

“This research grant is part of our mission to address critical knowledge gaps, foster innovation and bring hope to children and families with this rare and debilitating condition,” said Sarah Drislane, executive director of the KCNT1 Epilepsy Foundation.

A focus on common brain circuits to speed progress

Olguin pursued neuroscience in part to better understand her father’s Parkinson’s disease. “I was really interested in learning more about the brain and how it works, as well as genetics,” she explained.

She received her Ph.D. in biomedical sciences at the University of New Mexico. There, Olguin used EEG, a test to measure electrical activity in the brain, paired with a touchscreen technology in a prenatal alcohol exposure model. She studied attention and reward learning.

At the MIND Institute, she and Silverman have built on that work in the Silverman lab by using EEG to study seizures, sleep cycles and related brain activity in a KCNT1 mouse model. The model, created in collaboration with University of Missouri researchers, includes a gene variant that hasn’t been studied before.

The variant is critical because it is linked to two more severe types of KCNT1-related epilepsy: Early Infantile Migrating Seizures and Autosomal Dominant Frontal Lobe Nocturnal Epilepsy.

Olguin’s work focuses on seizures caused by fevers early in life. She wants to find out if these types of seizures increase the likelihood or severity of later seizures.

“Using this funding, Sarah and I will study behavior and EEG recordings in mice to answer this question and hopefully generate prime outcome measures to assess future treatments,” Silverman said. “Pilot grants like this are critical to collect data that can lead to more significant funding and advances.”

Olguin and Silverman hope to identify biomarkers — specific brain waves — that correlate with certain stimuli.

“We call these sensory-evoked potentials — specific events in the EEG that correspond to a visual stimulus like a flashing light or a specific audio tone,” Olguin explained. “If you repeat the same tone over and over, you get a very specific brain wave in the EEG. This can differ depending on whether you are typically developing or have a neurodevelopmental condition.”

Olguin also looks at differences in the brain between sleep and wakefulness. One thing that makes her work unique is that she studies brain circuits that are identical in mice and humans.

“My goal would be to get brain activity that is exactly the same in a mouse as in a human; then we should be able to target therapeutics for mice and humans.”

This would dramatically speed up the testing process for new potential interventions.

‘A natural born leader’

“Sarah is a natural-born leader,” Silverman said. “By increasing the number of translational, reliable, functional outcome measures in our wheelhouse, she is helping to create more opportunities for identifying and advancing successful medical interventions. This is Sarah’s talent.”

Silverman shared that Olguin has a “thing” for office supplies, a sign of her “top-tier” organizational skills.

“As a mother of two and researcher, it goes without saying that Sarah is an outstanding multitasker! She is as vibrant as her everchanging but always identifiable pink hair,” Silverman said.

Olguin’s work represents the Silverman lab’s first official study on KCNT1, but Silverman and her team have worked on several other rare conditions. These include groundbreaking research into two other neurodevelopmental conditions: Angelman syndrome and SYNGAP 1-related syndrome.

Before winning the Hartwell fellowship, Olguin was a trainee in the MIND Institute’s Autism Research Training Program. Funded by the National Institutes of Health, the two-year program merges the behavioral and biological sciences. The goal is to train autism researchers across disciplines.

Olguin said her experience in the program cemented her commitment to the field of neurodevelopmental conditions. Interactions with patient families and foundations, she shared, have been very rewarding.

“The parents are so involved, not only in the everyday of what their kids are doing, but they’re also advocating so much for the benefit of their children and the children in their community,” Olguin said. “It’s not just about them, and it’s fantastic to see.”

The UC Davis MIND Institute in Sacramento, Calif. is a unique, interdisciplinary research, clinical, and education center committed to deepening scientific understanding of autism and other neurodevelopmental conditions. It is a highly collaborative center, bringing together families, researchers, clinicians, community leaders and volunteers with the common goal of developing more personalized, equitable, and scientifically proven systems of support and intervention. The institute has major research efforts in autism, fragile X syndrome, chromosome 22q11.2 deletion syndrome, attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) and Down syndrome. More information about the institute and its Distinguished Lecturer Series, including previous presentations in this series, is available on the Web at https://health.ucdavis.edu/mind-institute/.