UC Davis study details use of extreme risk protection orders in California over first four years

Males and whites make up the majority of individuals subjected to gun violence restraining orders

In the first four years since California established extreme risk protection order (ERPO) policies, use of the relatively new violence prevention tool has increased substantially, a UC Davis Violence Prevention Program (VPRP) study has found. The majority of orders were requested by law enforcement officers for recipients who are male and white.

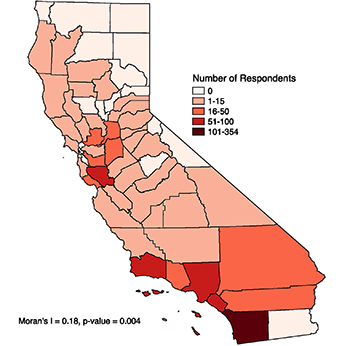

Map shows the number of gun violence restraining order respondents in California counties, 2016 to 2019. See larger map (PDF)

In 2016, California enacted a gun violence restraining orders; these are known nationwide as extreme risk protection orders (ERPOs). The policies enable law enforcement as well as individual family or household members who observe a person’s dangerous behavior to initiate a legal process that results in the temporary removal of that person’s firearms and ammunition. That process also temporarily prevents the individual from legally purchasing firearms and ammunition.

ERPOs help fill a gap in violence prevention policy by allowing individuals to intervene when someone who is not prohibited from owning a firearm poses an immediate risk of violence to themselves or others. ERPOs are a tool for targeted violence prevention when other risk-reduction interventions – such as arrest on probable cause, domestic violence and other protective orders, and involuntary mental health hold – are not appropriate or have failed.

The UC Davis research, published today in JAMA Network Open, is one of the first to detail the early use of ERPOs in California, the first state to establish such policies. The population-based study described the characteristics of ERPO petitioners and the individuals subject to them, as well as the patterns of ERPO requests over time and geographically. An invited commentary by practitioners seeing and enforcing ERPO policies describes the new VPRP study as “an important contribution to understanding state-level [ERPO] adoption.”

“About 90% of the 1,076 individuals who were subject to an ERPO in 2016-2019 were male and about three-fifths were white,” said Rocco Pallin, first author of the study and a VPRP researcher. “In nearly all cases, law enforcement officers filed the orders.”

The authors report a substantial increase in use of ERPOs over the four-year study period, with the largest increase from 2018-2019. They also found differences in ERPO use by county and significant geographic clustering among neighboring counties.

“Media coverage and awareness of these policies raised by local public champions in areas with the highest ERPO use, like Southern California, may have played a role in the more rapid uptake in the last year of the study period,” Pallin said.

Initial comparison of ERPO use in California in the early years of policy implementation with use in other states with such policies suggested slower uptake in California. The authors explained there might be factors affecting speed of uptake, including differences in the types of people who can initiate a petition, awareness of policies, law enforcement willingness to issue ERPOs, and other factors related to firearm culture to firearm-owner population. Additional research is needed to more carefully assess differences across states. To date, 19 states and the District of Columbia have ERPO or similar policies.

“ERPO laws, in California and elsewhere, have been established after mass shooting events, but evidence thus far points to their promise for preventing suicides, the overall leading cause of death from firearms in the U.S.,” Pallin said. “More research will allow us to better understand how ERPOs are being used to prevent suicides as well as harm directed at others.”

The researchers hope the study results will help inform policymakers and other stakeholders involved in implementing policies and outreach in California and in other states.

Co-authors on the study, “Assessment of Extreme Risk Protection Order Use in California, 2016-2019,” were Julia P. Schleimer, Veronica A. Pear and Garen J. Wintemute, all of the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program.

The research was supported by the Fund for a Safer Future (GA004701), the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center with funds from the State of California, the California Wellness Foundation (2014-255), the Heising-Simons Foundation and the UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program.

The UC Davis Violence Prevention Research Program is a multi-disciplinary program of research and policy development focused on the causes, consequences and prevention of violence. Studies assess firearm violence and the connections between violence, substance abuse and mental illness. VPRP is home to the University of California Firearm Violence Research Center, which launched in 2017 with a $5 million appropriation from the state of California to fund and conduct leading-edge research on firearm violence and its prevention.