The rising health crisis of congenital syphilis: what physicians can do

Congenital syphilis, a disease passed to babies during pregnancy, is increasing worldwide, with between 700,000 and 1.5 million reported cases annually over the past eight years. The disease can cause stillbirths, disability and death. To better understand this issue, a team of UC Davis pediatricians wrote a literature review, published in the journal Children, to illuminate this rising health threat and offer potential countermeasures.

“We have seen many mothers delivering with perinatal syphilis who did not get syphilis treatment during their pregnancies,” said Deepika Sankaran, assistant professor of clinical pediatrics and first author on the paper. “Many were not diagnosed during pregnancy. Some were diagnosed but did not receive adequate treatment. As a result, their babies had to be admitted to the neonatal intensive care unit (NICU) for intravenous antibiotics.”

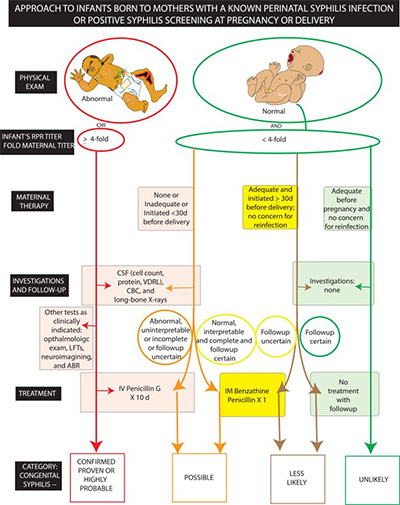

Syphilis is a serious bacterial infection that can affect the skin, eyes, nerves, heart, liver and brain. Maternal-to-fetal transmission of syphilis infection can occur in utero at any trimester through transplacental transmission or during delivery via direct contact with an infected lesion. Timely testing and treatment in the early stages is 98% effective in preventing congenital syphilis in newborns.

For some women, this intrinsic difficulty to diagnose can be compounded by their lack of prenatal health care due to poverty, substance abuse and mental health issues.

“For many of these mothers, the first time they actually seek medical care is when they deliver, so there is no way even to test them,” Sankaran said. “They don't have a primary care doctor or obstetrician, and when they get sick, they often go to the emergency room, which may be the only medical care they have before delivery. Even if they get tested, which is just a simple blood test, they may not show up for treatment.”

This cycle has serious consequences for babies. Because syphilis infection can spread to the brain, newborns often receive lumbar punctures to check their cerebrospinal fluid for bacteria. If the test is positive, they may have to spend the next 10 days in the NICU on antibiotics. Untreated babies may have long-lasting complications.

The authors, who also include Elizabeth Partridge, associate professor of pediatric infectious disease and Satyan Lakshminrusimha, Department of Pediatrics chair, senior author and medical illustrator, note that this is a worldwide problem. They looked at studies from China, Brazil and other countries and found syphilis rates often mirrored public health efforts, local customs, access to care and other factors.

Another issue is rapidly identifying newborns at risk of congenital syphilis because physicians are not always looking for it. There is a traditional mnemonic for intrauterine infections called TORCH: toxoplasmosis, other pathogens, rubella, cytomegalovirus and herpes. To better identify sick babies, the authors suggest amending this acronym to SCORTCH: syphilis, cytomegalovirus, other, rubella, toxoplasmosis, chickenpox, herpes and blood-borne viruses.

“Because congenital syphilis is the great masquerader, we should be testing pregnant women if we see any signs of it,” Sankaran said. “If a high-risk person comes to the emergency room, they should be screened. If they are diagnosed with the disease, we must find ways to get them treated so it is not passed on to the baby.”

Sankaran notes that the public health system must find better ways to optimize follow-up for those who are pregnant with perinatal syphilis, their partners and their babies. Passively waiting for them to seek medical care may not reduce risk. She believes community outreach and education are essential parts of any comprehensive solution.

“The No. 1 thing that must happen is political backing for more aggressive public health interventions to catch the disease early,” said Sankaran. “With outreach, we can seek out high-risk women, treat them and prevent syphilis transmission to their babies.”