Lessons from the ‘long COVID’ clinic

2 years into the pandemic, pulmonologists are still trying to understand the mysterious syndrome that can follow COVID-19 infections

When the UC Davis Post-COVID-19 Clinic opened in November 2020, Mark Avdalovic, a pulmonologist at UC Davis Medical Center, thought he knew what he would find with his patients.

He suspected that the wide range of persistent symptoms was likely driven by an inflammatory response, the body staying revved up months after the acute phase of the viral infection was over.

But that wasn’t what he found.

“A year later, I can say that inflammation is actually rare,” Avdalovic said. “We don't see a lot of patients who have lab tests that would indicate inflammation, like high C-reactive proteins or high D-dimer. We also don’t generally see autoantibodies for autoimmune diseases.”

Avdalovic, a professor of clinical medicine and vice chair for the Department of Medicine, is the director of the Post-COVID-19 Clinic. Although he and his colleagues haven’t found a single unifying thread, they have found patterns of symptoms, which they grouped into cohorts.

“There are patients who have a respiratory cluster of symptoms. They experience chest pain and cough during heavy breathing or if there’s a change in temperature,” Avdalovic said. Patients in other cohort groups experience:

- Shortness of breath, but no cough.

- Unusual tachycardia, or a higher than usual heart rate.

- Gastrointestinal symptoms, with abdominal pain and nausea.

- Rheumatologic symptoms like joint pains and muscle aches.

- New or worsening mental health symptoms.

“We have partners from the departments of Rheumatology, Cardiology, Pulmonary and several other specialties. The clinicians see patients when there is a symptom specific to their specialty,” Avdalovic said.

Research highlights the complex nature of the disorder

The widespread nature of the symptoms might be explained by an NIH study that found the virus can spread throughout the body, including the brain, and persist for months after the acute infection. Other new research points to four factors that may increase the risk of long COVID. They include the viral load, a certain type of autoantibodies (those that neutralize type I interferons), the reactivation of Epstein-Barr virus, and having Type 2 diabetes.

“These patients are clinically incredibly complex,” Avdalovic said. “It is not unusual to spend an hour and a half going through all their symptoms during the initial consultation.”

To date, the clinic has seen more than 400 patients with post-COVID conditions, all adults.

All patients must have evidence they had the disease. The largest group is between the ages of 27 to 54. There are more than twice as many women as men. The majority are Caucasian, which Avdalovic thinks is likely due to access, rather than any reflection of the disease, which is why he is implementing outreach efforts in diverse communities.

In the beginning, all the patients were unvaccinated because vaccines were not available. Now, they see some vaccinated patients, but not enough to know whether vaccines help to prevent long-haul COVID.

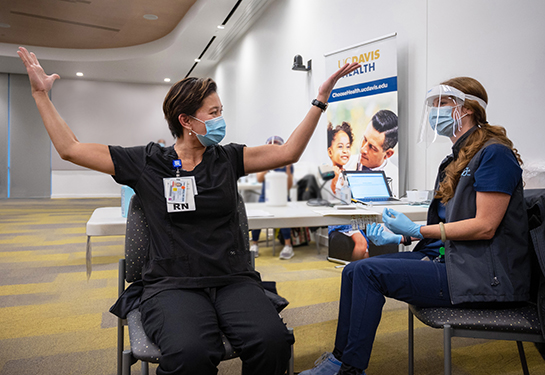

Clinic launched to address long COVID symptoms

UC Davis Health was one of only a handful of health systems in the U.S. at the time to create a clinic for patients who were presenting with a constellation of new or lingering symptoms following a COVID-19 infection, what came to be known as “long COVID.”

Research published in PLOS Medicine shows that about a third of COVID-19 patients, including those who had mild disease, have one or more symptoms three to six months after their diagnosis. As the number of infections in the United States reaches 80 million, that translates into approximately 26 million Americans potentially experiencing some degree of long COVID.

Another study identified more than 200 of these “long-haul” symptoms. The most common symptoms are fatigue, post-exertional malaise and brain fog. Other symptoms included visual hallucinations, tremors or vibrations, itchy skin, menstrual cycle changes, sexual dysfunction, heart palpitations, bladder control issues, shingles, memory loss, blurred vision, diarrhea and tinnitus. Just to name a few.

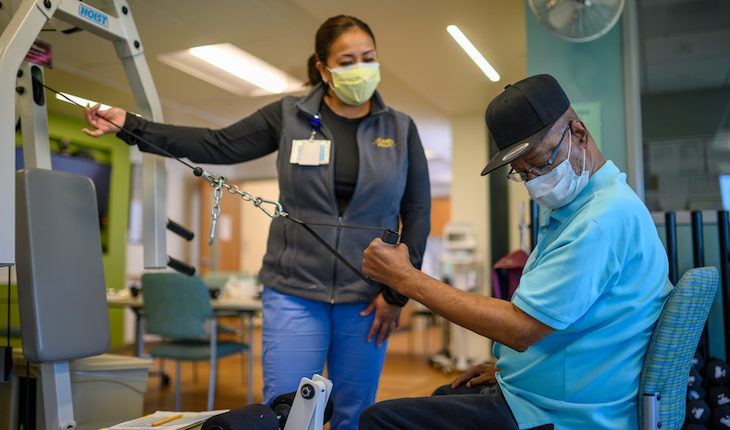

Rehabilitation helps many patients

Although usage of the term “long COVID” is widespread, none of the physicians in the UC Davis clinic particularly like it, calling it a non-formal description of unique clinical syndromes.

“It’s a difficult term because it encompasses a very wide range of symptoms that a wide variety of people with varying degrees of COVID severity experienced,” explained Bradley Sanville, a pulmonary and critical care physician who helped launch the clinic. The official term physicians use is post-acute sequelae of COVID-19, which they abbreviate PASC.

Sanville specializes in exercise physiology and the impact of disease on exercise tolerance. Like Avdalovic, he hasn’t necessarily seen what he expected to this past year from the long COVID patients.

During the pandemic, he worked shifts in the ICU, witnessing first-hand the damage COVID-19 can create in patients’ lungs.

“When we started the clinic, we expected that lot of the people who had been hospitalized and on ventilators would have really damaged lungs. We expected to see a lot of bad fibrosis. But personally, I haven’t seen much fibrosis,” Sanville said. “For whatever reason, the COVID-related damage seems to improve over time.”

In fact, many of his patients who had severe COVID-19 are essentially back to their normal lung function six months to a year after their illness.

Often, it’s the patients who were not hospitalized who have the lingering problems.

“Patients who had mild disease can be left with substantial shortness of breath and other symptoms for months, and even a year afterward, without significant improvement,” Sanville said.

Current tests don’t reveal what’s causing symptoms

Why these patients continue to experience symptoms is not clear. Many are given a range of tests, which can include a chest X-ray, CT scan, pulmonary function testing, echocardiogram, exercise stress tests and cardiopulmonary exercise testing. And in Sanville’s experience, these tests usually do not reveal what’s causing the patients’ symptoms.

“Imaging of their lungs, lung function and cardiopulmonary testing is often very normal. Nonetheless, they are limited in what they can do. It’s still a mystery, but at this time, most of the available evidence is pointing away from it being a lung problem,” Sanville said.

He notes that some recent studies suggest it may be that the muscles are unable to extract oxygen from the blood.

Imaging of their lungs, lung function and cardiopulmonary testing is often very normal. Nonetheless, they are limited in what they can do. It’s still a mystery, but at this time, most of the available evidence is pointing away from it being a lung problem.” —Bradley Sanville

Sanville generally prescribes inhalers for those who are short of breath. But for those who can tolerate exercise, he prescribes heart or lung rehab.

“Some are really reluctant in the beginning. They are afraid exercising might cause harm or make their symptoms worse. But most find it helpful. They feel better, and they are often surprised when we push them that they can tolerate more exercise than they thought,” Sanville said.

Patients generally improve over time

Avdalovic, too, has seen his patients improve with exercise. Other physicians at the clinic have had a good response with serotonin reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs) for symptoms of “long-haul.” He is also collaborating with the UC Davis Integrated Medicine team — which includes acupuncture, mind-body medicine such as meditation, and special diets — to design a forthcoming clinical trial.

“I think there are some nontraditional approaches that can help patients who have persistent fatigue, lack of concentration and even shortness of breath,” Avdalovic said.

The good news is that over the past year, Avdalovic has seen progress in most of his patients.

“Having the benefit of over a year’s retrospective, these patients get better over time,” Avdalovic said. “For about 75% of our patients, things eventually come back to either normal or near normal, but for some, it just takes a long time.”

To learn more, visit the UC Davis Post COVID-19 Clinic website.

Related stories