UC Davis drops race-based reference ranges from a standard kidney test

Health system one of the first in the nation to make the change to the estimated glomerular filtration rate or eGFR.

UC Davis Health has eliminated race-based reference ranges from a test that is routinely used to check how well a patient’s kidneys are functioning. The health system is one of the first in the nation to make the change to the estimated glomerular filtration rate or eGFR.

The change, which went into effect May 4, was inspired in part by students in the UC Davis School of Medicine, who were concerned about the impact of the test on racial health disparities.

According to the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases, Black Americans are almost four times as likely as white Americans to develop kidney failure. Black Americans make up 13% of the U.S. population but account for 35% of kidney failures. The leading causes of kidney failure for Black patients are diabetes and high blood pressure.

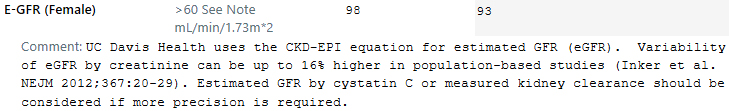

“Lab test results greatly influence decisions about patient care. We anticipate this change in the reference range for eGFR will lead to earlier detection and treatment of chronic kidney disease, more appropriate drug dosing and more eligibility for clinical trials and transplantation,” said Lydia Pleotis Howell, professor and chair of the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine.

The eGFR is calculated using an equation that includes variables such as age, gender, and blood creatinine, a chemical compound normally removed by the kidneys. The majority of laboratories in the United States also factor in race, with separate eGFR reference ranges reported for Black- and non-Black patients.

Race was added to this equation after a landmark 1999 study. The researchers found Black participants enrolled in the study had higher kidney filtration rates than non-Black participants with the same creatinine levels. A race-based adjustment, which allowed for higher creatinine levels, was created to accommodate this observed variation.

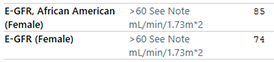

Example of an eGFR result with a race-based adjustment.

The race aspect of the test has come under scrutiny in recent years. Its inclusion may lead to underdiagnosis and undertreatment of kidney disease in Black patients. Institutions that have removed the race-based reference ranges include Brigham and Women’s Hospital, University of Washington, Vanderbilt University Medical Center and others.

Medical students initiate change

Momentum to change the test at UC Davis Health began last year.

In February 2020, Megan Byrne, then a fourth-year medical student, questioned the use of race in the eGFR as part of a class presentation for a race and health course taught by Associate Clinical Professor Jann Murray-García.

— Lydia Pleotis Howell

Later that year, on June 19, also known as Juneteenth, Rachael Lucatorto, a professor of internal medicine, asked her in-patient team if they knew what the African American celebration signified. As part of the discussion that followed, Bisrat Woldemichael, a medical student, questioned the rationale for using a race correction in the eGFR.

Murray-García and Lucatorto brought the students’ concerns to their colleagues for discussion. With support and encouragement from Dean Allison Brashear, a multi-specialty workgroup was formed to address issues around the test.

The group was composed of general internists, nephrologists, pathologists, lab professionals and clinicians from the Office of Health Equity, Diversity and Inclusion.

They began meeting in September 2020 to consider the impact of a potential change, including any unintended consequences. For example, a lower eGFR may make a person ineligible for medications that slow the progression of kidney disease and reduce the risk of cardiovascular disease.

Alex Ladenheim, a resident under the mentorship of Professor Nam Tran in the Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine, did an extensive review of the research. He also conducted a retrospective review of serum creatinine values and corresponding eGFR data from 376 patients over a one-month period to assess the impact of the change. The results showed that eliminating race from the eGFR would not lead to inappropriate treatment or false-positive results.

UC Davis Health has eliminated race-based reference ranges from the eGFR, which can measure kidney function.

“After reviewing clinical data and studies about the eGFR test, the workgroup found that the categorization of race, including the nature of race as a social construct, did not correlate to any clear genetic or metabolic differences,” said Brian Young. Young is a member of the workgroup and an associate clinical professor of nephrology.

Eliminating race may lead to earlier detection of kidney disease

In March, the National Kidney Foundation and the American Society of Nephrology released a joint statement that race modifiers should not be included in equations used to estimate kidney function. In the statement, Paul M. Palevsky, president of the National Kidney Foundation, said: “The use of race in clinical algorithms normalizes and reinforces misconceptions of racial determinants of health and disease. We must move beyond this if we are to address the racism and racial disparities that impede the care of people with kidney disease.”

In their own words

The change to the eGFR test was driven by UC Davis School of Medicine students. Both Megan Byrne and Bisrat Woldenmichael share their stories about the effort below.

Presentation for Race and Health course spurs change for common test

By Megan Byrne, who graduated from the School of Medicine in 2020

Juneteenth discussion of health inequities helps lead to change for common test

By Bisrat Woldemichael, a fourth-year medical student at UC Davis School of Medicine

In alignment with the recommendations in the joint statement, the workgroup moved forward to eliminate race from the eGFR equation at UC Davis Health.

Baback Roshanravan is an associate clinical professor of nephrology at UC Davis Health and a workgroup member. “The use of the eGFR equation does not completely capture kidney function,” said Roshanravan. “Creatinine is influenced by factors unrelated to kidney function, such as diet, nutritional status and muscle mass, which reduces its precision for estimating true kidney function. It should be interpreted in the specific clinical context with a holistic, patient-centered approach in mind.”

Successful implementation of the eGFR change was accomplished by clinical laboratory scientists and the health system electronic medical record and laboratory information system team.

The Department of Pathology and Laboratory Medicine is exploring offering a new test, cystatin C, which may be even more useful than other tests currently used for patients at risk for kidney disease.

An estimated one in three adults in the United States is at risk for kidney disease. Common risk factors include diabetes, family history, high blood pressure, heart disease and obesity. Learn about steps to improve kidney health.