UC Davis Health leads $2M program to improve eye care for people with diabetes

Program with other UC medical centers expands remote eye screenings to prevent blindness, particularly in underserved communities

Diabetes affects 34.2 million people in the United States. Diabetic retinopathy, a diabetes complication that affects blood vessels in the eye, is the leading cause of blindness in adults. Early detection and treatment are critical to prevent vision loss.

But fewer than 50% of the 3.2 million Californians with diabetes undergo their recommended yearly eye screening.

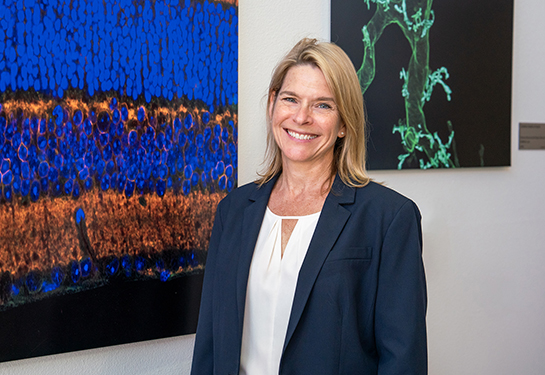

Glenn Yiu, a professor of ophthalmology at UC Davis Health, hopes to increase that number significantly.

Today, the UC Office of the President announced Yiu received a $2 million grant to lead an interdisciplinary program, the Collaborative UC Teleophthalmology Initiative, or CUTI.

The project, part of UCOP Multicampus Research Programs & Initiatives, is in partnership with medical centers at UC San Diego, UC San Francisco and UC Los Angeles. CUTI builds on a screening program Yiu launched at UC Davis Health in 2018.

The goal is to expand eye care access for diabetics, particularly for underserved populations. The project will utilize digital medical equipment for teleophthalmology or “remote” ophthalmology.

How teleophthalmology can be used for screenings

A key feature of the CUTI program is integrating digital eye screenings into routine care at primary care facilities or clinics for patients with diabetes.

The screening is simple and just requires the patient to look into a special camera. Known as a fundus camera or retinal camera, the machine takes high-resolution images of the interior of the eye. The images can detect changes that may signal diabetic retinopathy and other eye conditions.

After the digital image is taken at the primary care office or clinic, the results are sent to an off-site eye care provider for evaluation and diagnosis.

“Teleophthalmology provides a convenient way to get your eyes screened for diabetic retinopathy and other ocular disorders during a routine visit to the primary care physician,” Yiu said. “It also enhances eye care access for those who do not live near an ophthalmologist.”

Since launching a separate pilot teleophthalmology program at UC Davis in 2018, Yiu has improved diabetic eye screening rates by more than 15%, helping to make UC Davis Health one of the top performers in the country.

Screening for underserved patients

In addition to eye screenings at primary care facilities at UC health systems, the program will work with community clinics and Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHCs) to reach underserved members of the community.

In the Sacramento area, this includes student-run free community clinics, such as Clinica Tepati and Paul Hom Asian Clinic, that provide care in Sacramento’s inner-city neighborhoods. UC Davis Health is also working with Communicare Health Care Centers, a FQHC, to provide remote diabetic eye screening to rural areas of California’s Central Valley. The region has limited eye care access.

UC San Diego and UC San Francisco will also be engaging with community clinics in addition to primary care centers.

Training and identifying barriers

Because eye screenings are not a routine part of primary care, the program will train health care providers and identify the barriers that prevent the widespread adoption of remote eye screening.

Yiu noted that the COVID-19 pandemic increased awareness and acceptance of telehealth. He thinks this technology can reduce in-person health visits and improve access and adherence to preventative eye care.

The interdisciplinary CUTI team includes members from the four different UC campuses with expertise in public health, clinical informatics, and health economics who can address obstacles in clinical workflow, technology integration, and financial sustainability.

The retinal images taken during the four-year study will be collected in a centralized repository for research using artificial intelligence. Artificial intelligence may be able to identify eye diseases and predict the risk of cardiovascular events and strokes — simply from images of the eye’s interior.

“The introduction of artificial intelligence is another exciting development in teleophthalmology,” Yiu said. “The incorporation of AI for automated image interpretation allows for faster and more sensitive diagnosis of early eye disease.”

Remote diabetic eye screening is already available at UC Davis primary clinics in Midtown, Folsom, Elk Grove, and the Lawrence E. Ellison Ambulatory Care Center. Yiu and his team believe that remote eye imaging may be used in the future to screen for other eye conditions such as glaucoma and age-related macular degeneration (AMD). Over the four-year program, they hope to spread the word to improve awareness about preventative eye care.

“We are excited to start this project and hope to find a way to scale it up for all of California. Our long-term goal is to make it easy for people with diabetes to get their annual eye screening, so we can help people avoid preventable blindness.”

Resources