He had problems swallowing and sometimes choked when he talked. Was it anxiety?

A little over five years ago, Craig began having problems swallowing food. He would often chase down whatever he was eating with a piece of bread and extra water to get food through his esophagus. Difficulty swallowing is known as dysphagia, and it can have many causes.

Craig’s voice was also hoarse and would sometimes lock up when he was talking. This would make him feel like he was choking, creating a panic attack. “I couldn’t drink water to make it go away because it would cause more choking.”

Instead, he would practice deep breathing: a long dramatic, deep breath in, and then a long slow breath out. And then again.

Over time, the problem got worse. He also had a stiff neck.

Craig’s wife is a certified speech-language pathologist. “She would tell me, ‘This isn’t normal. This scares me. Why don’t you do something about it?’” Craig said.

The couple live in the southern Ozark region. Craig was fit — did not smoke, did not drink — but he had other aches and pains, including pelvic and back pain. Over a period of several years, he had bone spurs removed from his ankle, elbows and shoulders.

He thought the problems with swallowing were related to aging. Or maybe something to do with nearly three decades of rigorous military service. Craig spent 13 years in the Army and 17 years in the Air Force.

Nights were difficult. Craig didn’t snore or appear to have sleep apnea, but he still had choking attacks when he slept. Waking, gasping for air, made him feel apprehensive about sleeping most nights. He kept an inhaler and water near the bed.

His doctor prescribed a medication used to treat anxiety and panic disorders, but it didn’t help.

CT scan reveals source of choking

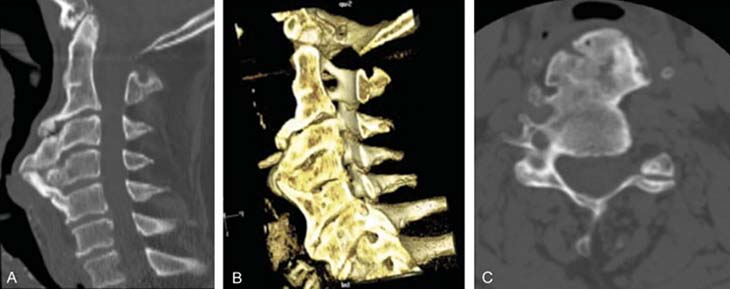

Last fall, a CT scan revealed it wasn’t anxiety that was causing Craig’s throat problems.

The image showed massive bone spurs — known as osteophytes — growing from the front of his cervical spine. The osteophytes were pressing into his esophagus, essentially pinching it closed.

The condition is known as diffuse idiopathic skeletal hyperostosis, or DISH. It is also known as Forestier's disease. DISH is caused by the buildup of calcium deposits in the ligaments and tendons and a hardening and overgrowth of bone. The disease can be mild for many people.

After years of choking, Craig finally had a diagnosis. “It was completely unexpected,” he said. Craig reflected on the other bone spurs he had removed and wondered why no one had made the diagnosis until now.

Additional imaging tests revealed the bones in his neck weren’t the only location with abnormalities. An X-ray of his pelvis showed jagged edges of bone along the top (iliac crest) and bottom (the “sit bones”) that should have been smooth. His thigh bone and parts of his spine had bone spurs with accompanying pain.

Craig was concerned about the disease’s possible progression. But more immediately, he knew he needed surgery on his neck to ensure he could breathe, swallow and talk. And he knew that any surgery on the spine would inherently carry risks.

People can have DISH and not know it

Kee D. Kim is the chief of spinal neurosurgery at UC Davis Health and co-director of the Spine Center. His expertise is complex spine surgery for degenerative diseases, tumors, trauma and unsuccessful surgeries performed elsewhere.

According to Kim, even though most people haven’t heard of it, DISH is actually not rare. “It is often undiagnosed because many people with DISH have little or no symptoms. The most common symptoms are mild to moderate pain and stiffness in the neck or back and loss of range of motion where it’s involved,” Kim said.

The cause is unknown. And there’s no known way to prevent it. DISH is considered a type of arthritis and primarily affects tendons and ligaments around the spine. In the United States, it is estimated that 25% of men and 15% of women older than 50 years have DISH. After age 80, the percentages go up to 35% for men and 26% for women.

DISH can be easily diagnosed with X-rays, but the symptoms are often attributed to aging, so physicians may miss the disease. With DISH involving the spine, images show a flowing abnormal bone formation along the front or sides of the vertebrae.

But DISH can be progressive and can cause complications, including numbness and tingling from pinched nerves or even paralysis from relatively mild trauma. Or, in cases like Craig’s, it can put pressure on the esophagus.

Deciding where to get the operation

Craig was referred to a spinal surgeon in his area who had only done a few spinal surgeries like the one he needed. The surgeon told Craig he needed to lower his expectations.

Around this time, his wife found a study from Dr. Kim and his colleagues in the Department of Neurological Surgery at UC Davis: “Dysphagia Secondary to Anterior Osteophytes of the Cervical Spine.” Published in 2015 in Global Spine Journal, the study describes treatment and outcomes for two patients with DISH symptoms similar to Craig’s.

Although conservative treatments are often tried for people with difficulty swallowing due to DISH — swallowing therapy, anti-inflammatory medication, steroids and muscle relaxants — Kim’s paper showed surgery had resolved the two patients’ trouble swallowing.

Craig was relieved when he read the study. He felt like he had found his path forward. He emailed Kim the details of his condition and asked if he could operate on him. Kim’s reply was immediate and encouraging.

UC Davis Spine Center sees many patients from out of state

As a spinal surgeon for complex cases, Kim sees many patients from out of state, although not usually for the type of surgery Craig needed. “But his case was very severe, so I feel he made the right decision to come to UC Davis.”

For the surgery, Craig needed an out-of-network referral from his insurance provider. The process took a couple of months, and he was helped by Lori Knight, the neurosurgery spine case manager at the Spine Center. The referral required a statement from Craig’s doctor that an experienced surgeon was unavailable within 100 miles and the surgery was vital to Craig’s quality of life. Craig got his referral.

On Super Bowl Sunday this year, Craig and his wife flew to California. They met with Kim on Monday to go over Craig’s complete medical history. On Thursday, it was time for the surgery.

He needed surgery because his swallowing was getting worse, and he could have easily choked on food blocking his airway and stopping his breathing. Or if a small food particle went down his lung, he could end up with aspiration pneumonia.—Kee D. Kim

Team effort to remove bone spurs

Removing the unwanted bone growths from the vertebrae in Craig’s neck was a team effort. Marianne Abouyared, from the UC Davis Department of Otolaryngology, specializes in head and neck surgery. She began the surgery, creating an entrance from the front of the neck. Then, under a microscope, Kim and Bart Thaci, neurosurgery chief resident, very carefully drilled and removed the bone spurs from Craig’s spine.

The spurs extended from his second cervical vertebrae, C2, to his first thoracic vertebrae, T1. Before they closed the wound, they applied bone wax on the cervical spine to reduce the chance of bone spurs growing back. The last step was a CT scan to confirm they had removed the necessary amount of bone and that the esophagus was no longer under pressure. Then Craig was on to recovery.

“He needed surgery because his swallowing was getting worse, and he could have easily choked on food blocking his airway and stopping his breathing. Or if a small food particle went down his lung, he could end up with aspiration pneumonia,” Kim said.

Learning how to swallow

After the surgery, while he was recovering in the hospital, Craig had swelling and pain in his throat. Because of his anxiety from years of choking incidents, he did not want a feeding tube.

For three days, he couldn’t swallow anything, not even his own saliva. “I was spitting into a cup,” Craig said. Even with intravenous fluids, Craig lost weight.

When he was able to eat small amounts of liquid food, he would start coughing. “All the sensations were tickling. I was coughing all night for weeks.”

Craig essentially had to learn how to swallow again. He slowly made progress. After three days, he could eat well enough to be safely discharged. It helped that his wife was a certified speech-language pathologist, trained in swallowing disorders. In the hotel where they stayed for a week after the surgery, Craig was able to drink protein drinks. He was gradually regaining the normal function of his throat.

Before flying home, he had a post-operative checkup at the Spine Center with Kim. Kim told Craig not to be impatient, and swallowing might get more difficult before it gets better.

This was true. Back home, he could hardly swallow medications. He was eager to eat all the foods he liked, but they still made him choke.

Now, four months after the surgery, Craig is healing well. “The good news is, I can swallow, talk and breathe normally.” And after years of choking at night, he’s also sleeping better.

Craig knows he will likely need additional surgeries for bone spurs in other parts of his body. “Being able to breathe normally has given me my life back,” he said. He is grateful to Kim, the surgical team, the Spine Center team and the hospital nursing staff.

Kim is glad to help patients like Craig. “Patients are usually under a lot of stress because they are afraid that a food particle or even water may go down a wrong tube and they may choke to death. After surgery, patients will say that I changed their life or saved their life. When they can swallow normally after being constantly worried — that is a huge improvement in their and their family’s quality of life.”

Craig hopes his story helps people learn about DISH. “It’s insidious. It creeps up on you, and bone spurs from DISH can actually be life-threatening.”

And although bone spurs can come back, his prognosis is good. “I am probably going to be good for a while,” Craig said. And now he knows what symptoms to look for and the value of getting additional medical opinions.

Learn more about DISH here.